Most people, if they have heard of D.H. Sleem at all, know the name because of his Alaska maps. And they were splendid, deserving of lasting admiration.

But there was much more to the man than geography.

Author Linda K. Jacobs, in her books “Gendering Birth and Death in the Nineteenth Century Syrian Colony of New York City” and “Strangers No More: Syrians in the United States, 1880-1900,” referred to Sleem as “apparently brilliant and certainly a polymath,” which is a person of far-ranging knowledge or learning.

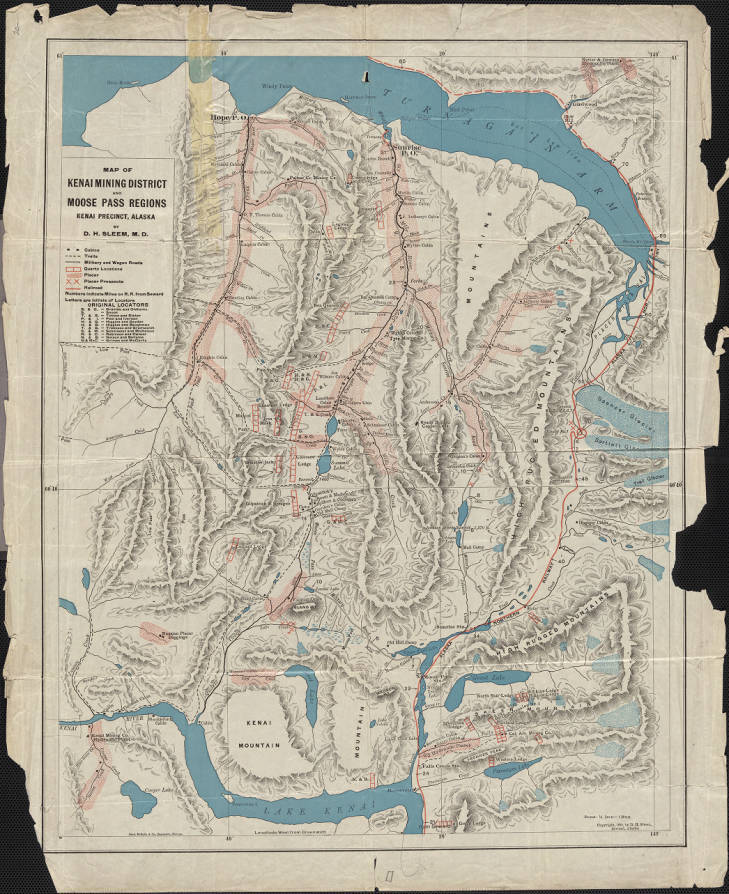

To residents of Southcentral Alaska, his most enduring legacy is almost certainly his hand-drawn 1910 “Map of Kenai Mining District and Moose Pass Regions, Kenai Precinct, Alaska.” The map, one of at least four created in the last years before his death, was elegantly crafted, detailed in its delineation of cabins, placer mines, ore-bearing lodes, trails and wagon roads, in addition to being geographically sound enough to allow it to be a useful travel and exploration tool for several decades.

As for the mapmaker himself, he was David Hassan Sleem, a Seward physician whose name and title were professionally listed this way: D.H. Sleem, A.B., M.S., M.D.

Sleem was born in Syria on April 28, 1860, probably under the Persian form of his name, Davoud Hassan Selim, according to a 1914 listing of case files from the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service. At the time of his birth, Syria was controlled by the Ottoman Empire, so many sources refer to Sleem as a Turk.

His family was Presbyterian, and Sleem — who may at one time have been a Druze, formerly of a Muslim sect now generally considered heretica — graduated from Syrian Protestant College (now the American University in Beirut) in 1879, when he was only 19. He tutored at the college for several years and earned his medical degree in 1887. One year later, he immigrated to the United States and settled in New York City, where he quickly earned a second medical degree at New York University. In 1897, he was naturalized as an American citizen.

There was a Syrian community in New York, but Jacobs says Sleem never really became a part of it. He lived and had a medical practice miles away on West 97th Street, and his clientele were mainly native-born Americans who lived uptown.

Sleem did occasionally tend to Syrian-born patients, however, and he once had his name in New York newspapers when he rescued a female Syrian peddler who had been committed to an insane asylum because no one could understand the native language she was speaking.

His work days were split between his private practice and the Bellevue Hospital. He began and ended each day with office hours for patients in his private practice and spent the intervening seven hours working at the hospital.

But Sleem’s accomplishments were not confined to his patients. He patented at least two surgical devices, including a “surgical applicator” that was noted in the Sept. 7, 1895, issue of Scientific American. He also earned a master’s degree from Columbia University in 1896 with a thesis on the construction of an electric train. And he authored a short book on insurance investments with the long and unwieldy title of Equity System of Cumulative Tontine Investment: A System of Equitably Distributing the Profit Developed by Life Insurance and Tontine Principles as Applied to the “Bond Enterprise.”

He was one of only two Syrian member of the American Oriental Society. He promoted literacy and literature in general, and was a fine gardener, a good businessman, a successful orator and an accomplished musician. Like many intellectuals of the time, he was also interested in the paranormal and once hosted an evening with a supposed psychic.

Despite his keen mind, his versatility, his high level of activity and his myriad successes, however, Dr. Sleem had an Achilles heel: a weakening heart. After being diagnosed with heart failure, he was advised to move to a colder climate in the belief that it might prolong his life. So in 1899, he abandoned his New York medical practice and headed north.

According to Jacobs, Sleem joined the gold rush in Atlin, British Columbia, and then moved on to the Yukon Territory boom towns of Eldorado Creek and Dawson City. Seward historian Mary J. Barry said Sleem also lived briefly in Nome, and, before settling in Seward in 1903, spent some time in Valdez, considered the gateway to the interior of Alaska before Seward garnered that distinction. Jacobs called it “likely” that Sleem practiced medicine at each place he lived before coming to Resurrection Bay.

In Seward, he quickly made himself at home and integrated himself into his new community.

In 1904, on 4th Avenue, next to the future site of the Van Gilder Hotel, he built a large, two-story log home, dubbed “Sleem’s Hall.” There, he set up his medical practice but also made his spacious accommodations available for community gatherings, such as meetings, dances, public lectures and Sunday school.

At a Sleem’s Hall birthday party for a Mrs. Tecklenburg in 1904, according to Jacobs, Dr. Sleem himself sang an “affecting rendition” — and ironic, given his medical condition — of the Charles K. Harris tear-jerker, “I Am Wearing My Heart Away for You.”

The following year, he surrendered his heart and his life as a bachelor when he married a musically talented local woman named Lillian who was 20 years his junior.

Meanwhile, Dr. Sleem continued his private medical practice; joined in a freight-transfer business with another Syrian, the teamster George Salami; became active in the Methodist Church and the local Chamber of Commerce, a member of the school board and of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, and was the city health officer and the president of the Seward Literary and Musical Society.

As Barry said, he was “held in high regard” in Seward, and even an occasional problem usually turned out well in the end.

For instance, Barry recalled that in December 1908 the Sleems’ house caught on fire. They had been away when the flames were noticed: “The Reverend Pedersen rang the church bell as an alarm, but it took a while before people realized it was ringing for a fire. The fire department saved the house, but the roof and Dr. Sleem’s books were ruined.”

Fortunately, the doctor’s piano and medical instruments, the couple’s furniture and clothes, and a map Dr. Sleem had just completed were saved. By February of 1909, the house had been repaired and the Sleems were back at home.

Although Dr. Sleem would live only four more years, his legacy would survive for more than a century, as will be revealed in Part Two.

• By Clark Fair, Special to The Clarion