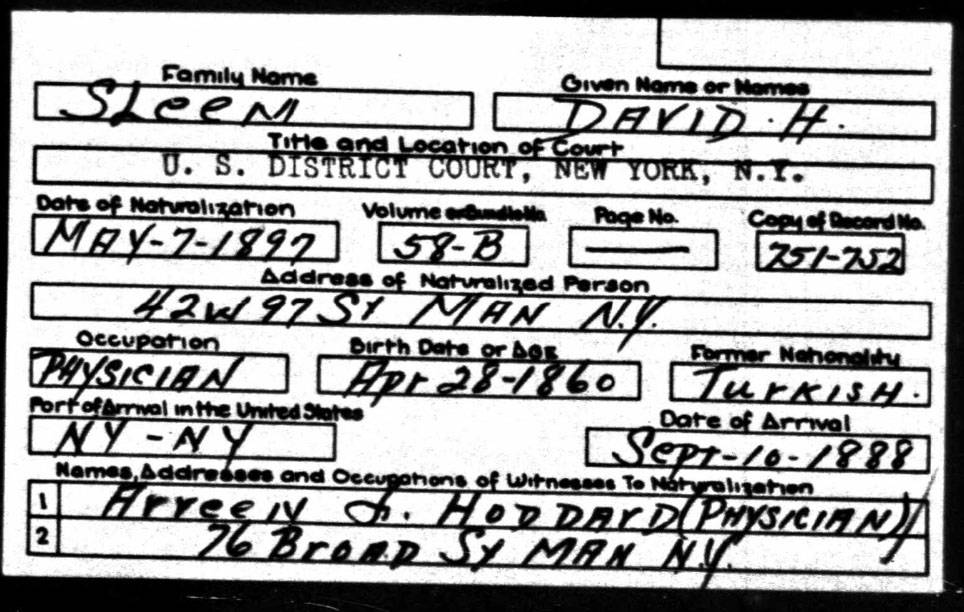

AUTHOR’S NOTE: In Part One, the Syrian-born David Hassan Sleem immigrated to New York City in 1888 and spent more than a decade there as an accomplished physician before heading north to try to prolong a life fraught with a serious medical condition. Settling in Seward in 1903, he aimed his myriad talents toward the betterment of his community.

A headline in the Seward Weekly Gateway on Monday, Oct. 13, 1913, provided readers with a shock: “Dr. D.H. Sleem Dies, a Victim of Heart Disease.”

The article itself got bluntly to the point: “Dr. David H. Sleem of Valdez dropped dead from the effects of heart disease Saturday afternoon. He was attending a patient, and suddenly complained of a severe pain in his side. Soon after, he expired. But an hour before, he said he never felt better in his life.”

Sleem was buried a couple weeks later in Lake View Cemetery in Seattle. He was survived by his wife, Lillian, who had moved after his death to Bremerton, Washington.

The brief article referred to Sleem as “an old timer of Seward,” a town in which few people could qualify for old-timer status since the community by that name had existed for only about a decade. Still, Sleem had lived there until moving to Valdez in 1911, and had been deeply ingrained in Seward society.

Seward historian Mary J. Barry, who in her research dug extensively into old newspapers of the time, provided these glimpses of the breadth of Sleem’s activities:

“On Dec. 6, 1904, Martha Herning, under the care of Dr. Sleem, gave birth to a son, George Stanley Herning, premature but healthy.”

“Dr. Sleem and his niece, Liza Sleem, established a Sunday school for the young people of Seward.”

The two Sleems were lauded in the inaugural issue of the Seward Gateway (Aug. 19, 1904), when editor/publisher Randall H. Kemp said, “Too much credit cannot be given Dr. D.H. Sleem and his niece … for the unselfish interest that they have manifested in creating a moral influence and providing intellectial [sic] entertainments for the citizens. Dr. Sleem’s [free] lectures … are so highly interesting that neither residents nor visitors should miss them.”

In the fall of 1908, Dr. Sleem was chosen as secretary of an organization to collect and send an exhibit to the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition at Seattle. Sleem created a hand-drawn map of the Susitna and Cook Inlet region as part of the exhibit.

In November 1908, Sleem organized a Latin club.

In the spring of 1910, Dr. Sleem was involved in selecting delegates to the Alaska territorial convention.

In 1909, Sleem was elected to the publicity committee of the Seward Commercial Club, part of an effort to boost the Gateway City as “the most logical port of entry to the Iditarod.”

Sleem was elected as board clerk of the local school board in 1908. He was reelected in 1910, and acted as emcee during that spring’s commencement exercises.

In 1904, an Episcopalian service was held in Sleem’s spacious home on 4th Avenue. Each Sunday during this year, Dr. Sleem gave free lectures.

As a physician, Sleem provided general medical care, performed operations routinely and autopsies when necessary, and once even read the burial service for a young man who had committed suicide.

In May 1909, he ceased most of his private practice in Seward and took a job as physician and surgeon for the Alaska Central Railway, and the Seward-based railroad contractors, Snow and Watson, who hoped to connect Seward to Iditarod and other points in Interior Alaska. He established a general hospital for both railroad and private medical patients, and he devoted time and energy to promoting the rail route and Seward itself.

For the Seward Commercial Club, Sleem wrote an article about the Seward-to-Iditarod route, and the piece was reprinted in the Alaska-Yukon Magazine. When he and Lillian traveled, even as far away as Seattle, he often delivered illustrated lectures about the beauty of Seward to community groups and at schools.

When the railroad work ceased locally and the Seward population began to decline, Dr. Sleem decided to return to Valdez, where he had lived briefly prior to settling in Seward. In 1911, the Sleems made the move, and, according to historian Linda K. Jacobs, Dr. Sleem set up a medical practice on McKinley Street.

As he done in Seward, he was quick to make a good impression in Valdez. On the day of his funeral two years after his arrival, Valdez businesses and public schools closed in his honor. Since he had been a strong promoter of a project to furnish a free reading room for Valdez residents, “The Reading Room Sleem Memorial” was established in his honor.

But the memory of D.H. Sleem might have faded completely over the years if not for the publication of his four tinted, hand-drawn maps: Sleem’s 47×30-inch, fold-out Map of Central Alaska; the Map of the Willow Creek Mining District; the Map of Iditarod, Kuskokwim and Innoko; and, most important to the Kenai Peninsula, the Map of Kenai Mining District and Moose Pass Regions.

When the Palmer Historical Society pondered his Willow Creek map in a 2008 newsletter, the respect for Sleem’s craftsmanship was evident: “How,” said the newsletter article, “could Dr. Sleem make such a detailed map in 1910? There were earlier maps, but without detail at this scale.”

As possible sources for Sleem, the historical society suggested Capt. James Cook’s charts from 1778, an accurate regional topographic map produced by the U.S. Geological Survey in 1900, the Johnson and Herning map from 1899, and a Matanuska River coal region map from the USGS in 1905. Sleem, the PHS asserted, must have had access to those documents and relied on them for much of his information.

But Sleem’s detail went further than that. Text on his Central Alaska map stated that his information had been “compiled from U.S. Government and R.R. Surveys, reliable prospectors and personal reconnaissance by D.H. Sleem.”

“These regional maps,” said the historical society newsletter, “shared an important resource—the wisdom of natives, traders and prospectors.” The maps showed placer and lode mining areas, trails, wagon roads, proposed rail routes, cabins and roadhouses.

Patricia Ray Williams, who grew up in Seward and spent most of her 104 years in the town she loved, had saved a bundle of old Sleem maps and resisted calls to toss them into the trash. It was one of those maps that found its way to the Palmer Historical Society, which created reproductions for public sale and historical appreciation.

As long as the maps continue to be valued, the legacy of David Hassan Sleem will go on.

• By Clark Fair, for the Peninsula Clarion