In 26 years of building roads in Alaska, Ralph Soberg had seen only one man die during a bridge-construction project. That man, a friend to Soberg, was known to him and his other Alaska Road Commission colleagues as “Doc” MacDonald.

When he died in the spring of 1948, Doc was identified in newspapers as 48-year-old Alec Hardin MacDonald, an eight-year ARC employee who was survived by a Kenai widow named Helen and two teenage children.

But those basic facts belied the complexity of the man.

There was much more than met the eye when it came to Doc MacDonald. His full Alaska history—revealed in news reports, genealogical records and a Soberg memoir called “Bridging Alaska: From the Big Delta to the Kenai”—was far from his full life story.

Even now, with much more of the truth laid bare, mysteries remain—mysteries that frustrate researchers and writers seeking a more complete account.

Beginning with the Ending

In the spring of 1946, the Anchorage district superintendent for the Alaska Road Commission informed Ralph Soberg that Congress had set aside $3 million for a new highway from Mud (now Tern) Lake, between Moose Pass and Cooper Landing, through the Kenai National Moose Range, and all the way to Homer.

Soberg, as a foreman, was placed in charge of the north-end construction zone, while a second foreman, Claude Rogers, was assigned to the southern zone. By Christmas, the northern crew had completed a bridge across the Moose River, just above its confluence with the middle Kenai River.

By springtime 1947—just before a conflagration known as the Kenai Burn began incinerating a 300,000-acre swath of the central Kenai Peninsula—the ARC had established a work camp at Hidden Creek. The original highway route then was what is known now as Skilak Lake Road.

That summer, as Rogers and his crew ground their way northward, Soberg and his boss, A.F. “Gil” Ghiglione, ran a skiff up and down the Kenai River to look for a bridge site, which they located at what would soon become Soldotna. Later that same day, a bit farther upstream, they also found a site near the mouth of Soldotna Creek that they liked for a permanent ARC maintenance camp.

In early spring 1948, Soberg and Ed Hollier towed the ARC pile driver from the Moose River bridge site to the Kenai River bridge site. After they rigged it up with a boom for handling steel, that part of the construction work got under way.

On May 5, 1948, at about 4 p.m., Doc MacDonald was standing atop a piece of steel about 60 feet above the river. With Soberg assisting him just below, MacDonald was holding on to a cable with one hand while attempting with the other hand to help fit a second piece of steel into place. The crew was having difficulty positioning the new beam, and at some point the beam on which Doc stood was jolted, causing the cable to jerk free of his grip.

MacDonald lost his balance and toppled from his perch. Soberg reached out but had no chance to catch his friend or arrest the fall.

Wearing a belt weighted with up to 50 pounds of bolts and tools, MacDonald hit the river and was immediately submerged in about 10 feet of cold water.

“I yelled for someone to get the boat out,” Soberg wrote in his memoir, “and a couple of fellows did, rushing out as fast as they could with a pike pole (a long pole with a pointed end and a hook protruding from the upper side of the shaft) … Doc came up just once. I yelled at him to drop his tool belt, and all he said was, ‘I can’t.’ Back down he went. He never came up again.”

From his vantage point about 50 feet above the water, Soberg saw the men in the boat reach the place MacDonald had gone under. “The crook in the pike pole just missed his neck when they tried to hook on to him,” wrote Soberg. “Soon he went down so far (that) I couldn’t see him anymore.”

The body of Alec Hardin MacDonald was found two days later, on May 7, in about 12 feet of water and approximately 250 feet downriver from the bridge site.

The drowning temporarily stymied production on the bridge, as a number of construction crewmembers were reluctant to climb out again over the cold river, but after two days Soberg, who was also grieving, convinced his men that the work had to resume.

MacDonald’s body was transported to Anchorage for funeral arrangements and a burial. His widow and her two children, who had been living in a Quonset hut at the ARC camp in Kenai, also soon departed for Anchorage. Soberg, who had known MacDonald since about 1940, provided the background and accident information for Doc’s death certificate.

Work on the highway project continued. The bridge was completed that summer, and before the summer of 1949 the northern and southern ends of the highway were joined and then graveled. The route opened officially with a ceremony on Sept. 6, 1950, at the Kenai River bridge. By 1958 the entire Sterling Highway had been paved.

Pieces of the Puzzle

In his memoir, Ralph Soberg wrote that Doc MacDonald had earned his nickname because he had studied dentistry before turning to roadbuilding. When an earlier marriage deteriorated and finally failed, said Soberg, MacDonald “was so burned up about it that he dropped his studies and took off for the bush country.”

Although he halted his studies, Doc still had skills. During the winter of 1940-41, MacDonald used those skills to help Soberg with a bad toothache. “We had no medical benefits or sick leave in those days,” Soberg wrote, “and I didn’t want to spend the money to go clear to Anchorage or Fairbanks to see a dentist, so Doc said he’d take care of it for me.”

MacDonald had a foot-operated dental drill, which he used in this special case. “He got some gold dust from someplace,” Soberg said. “He ground the tooth down—I took a drink of whiskey once in a while when the pain got too bad—and after several sessions, by golly, he got a crown fixed up and fastened on my tooth. It held for years before it had to be replaced.”

In his personal life, according to Soberg and news reports, MacDonald had met his wife, Helen, when they both were living in the village of Takotna in Interior Alaska. The 1940 U.S. Census shows him as a Takotna resident, a 39-year-old, divorced ARC truck driver. According to other documents, he married the thrice-divorced mother of seven, Helen Irene O’Halloran, on Aug. 25, 1943, in Fairbanks.

O’Halloran had been born in 1901 as Helen Kozevenkoff in St. Michael to one Russian and one Native parent. MacDonald, said his draft-registration card, had been born in 1900 in Chautauqua County, Kansas. When Doc drowned, only two of Helen’s seven children—Charlie and Helen—were still living at home.

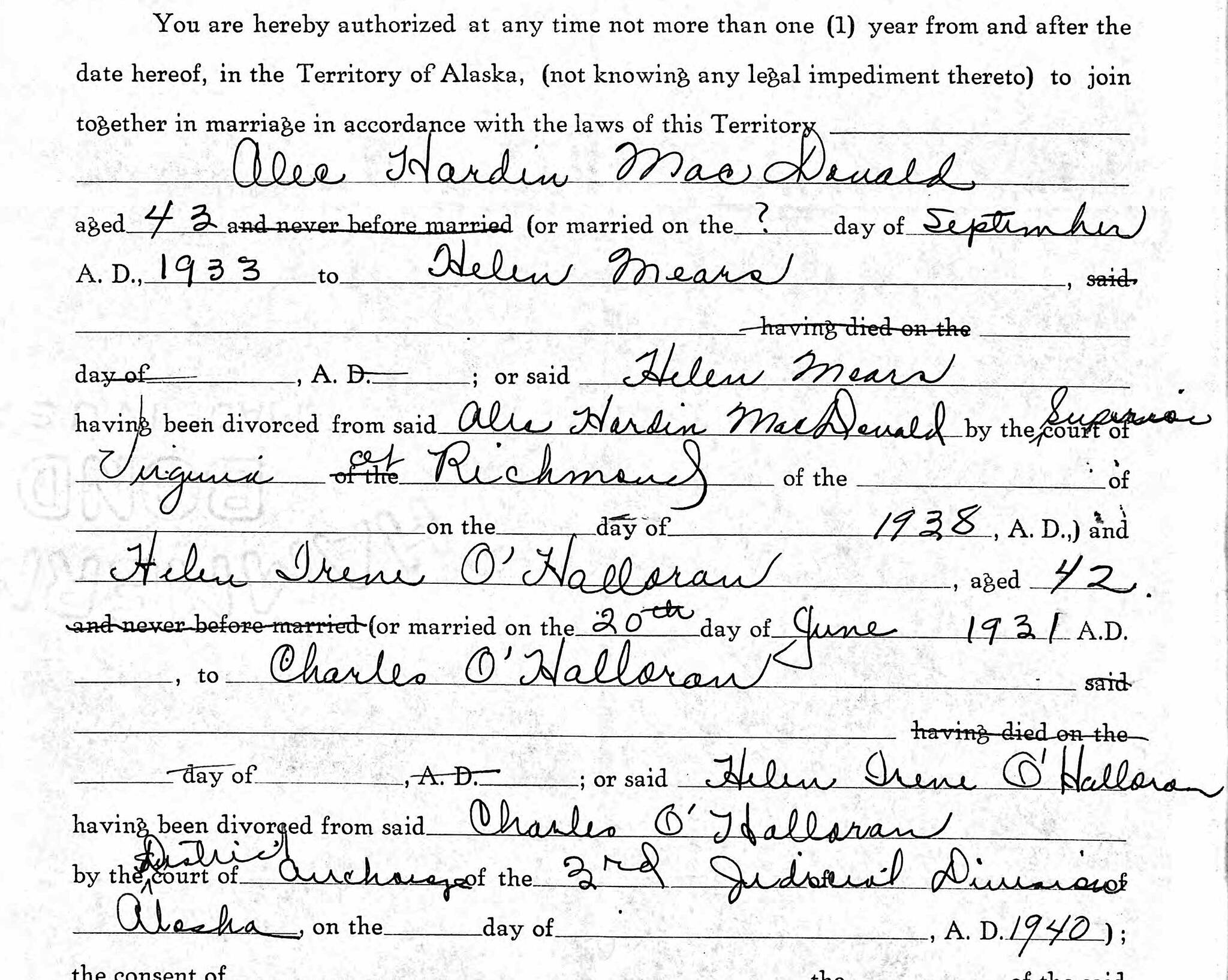

On their marriage certificate, MacDonald stated that he had been married once before, in September 1933, to yet another Helen—Helen Mears—and that he had been divorced from her on an unspecified date in 1938 in Richmond, Virginia. (Helen O’Halloran had been divorced from her most recent husband since 1940.)

Other than the 1933 reference to a previous marriage and a previous Helen, no records pertaining to the earlier life of Alec Hardin MacDonald, anywhere in the United States, could be found. In fact, the earliest verifiable date placing MacDonald in Alaska appeared in the 1940 census.

In that census enumeration, MacDonald was specifically asked where he was living on Oct. 1, 1934. His answer was Alaska; however, beyond his say-so, no other evidence of his presence in Alaska during that year has yet appeared.

In fact, further research throws into doubt the accuracy of MacDonald’s claims about dentistry, his previous marriage, the year and place of his birth, and many other details.

But an extensive search through newspaper archives did unearth this intriguing note from the Jan. 15, 1962, edition of The Nome Nugget:

“Mrs. John Howell wants information on John Floyd King, who died in Anchorage between 1948 and 1950 and is believed to be buried in Nome. His wife was known in Alaska as Helen MacDonald. His sister Mary King Cameron would like to communicate also with Helen MacDonald. Address is 1018 Denon Drive, Pocatello, Idaho.”