AUTHOR’S NOTE: According to news reports and a memoir by Ralph Soberg, “Doc” MacDonald was a 48-year-old employee of the Alaska Road Commission when he drowned in the Kenai River after falling from a bridge construction site in 1948; however, his existence prior to 1933 appeared to be a blank slate.

Fourteen years after the death of Alec Hardin “Doc” MacDonald in May 1948, a woman purporting to be his sister, Mary King Cameron, was hoping to speak to MacDonald’s widow, Helen. To this end, someone named Mrs. John Howell had informed the news staff at The Nome Nugget of Cameron’s wishes. The newspaper complied by publishing a brief announcement.

The kicker was that the brother of Mrs. Cameron — and therefore the widow of Helen MacDonald — was said to be a man named John Floyd King.

Genealogical research and the testimony of Cameron’s grandson, Gregory Brennan, has revealed that Mary Elizabeth Cameron (nee King) was, indeed, the sister of John Floyd King. Both of them were born in Ava, Douglas County, Missouri, to John Thomas King and Melissa May (Bean) King near the end of the 19th century. Both of their birth years vary, depending upon the documentation, but John Floyd King was probably born in 1897, while Mary Elizabeth King was likely born in 1899.

John T. and May King had two other, younger children, sons named William (“Bill”) and Omer.

According to a paper called “Childhood Memories,” penned by Mary Elizabeth King, her father was initially a farmer. The family moved from Missouri to Oklahoma briefly in about 1904, she wrote, and then to Sedan, in Chautauqua County, Kansas, shortly thereafter. Over the succeeding years, John Thomas King was primarily a mason, but he also taught school and worked as a town marshal.

In about 1912, the Kings packed up and moved again — this time to Blackfoot, Idaho.

From this point until 1920, the life of John Floyd King — who apparently went by Floyd, perhaps to avoid confusion with his father — is fairly well documented. The 1920s, however, is, so far, remarkably unclear and free of details.

A War, a Wedding and a Disappearance

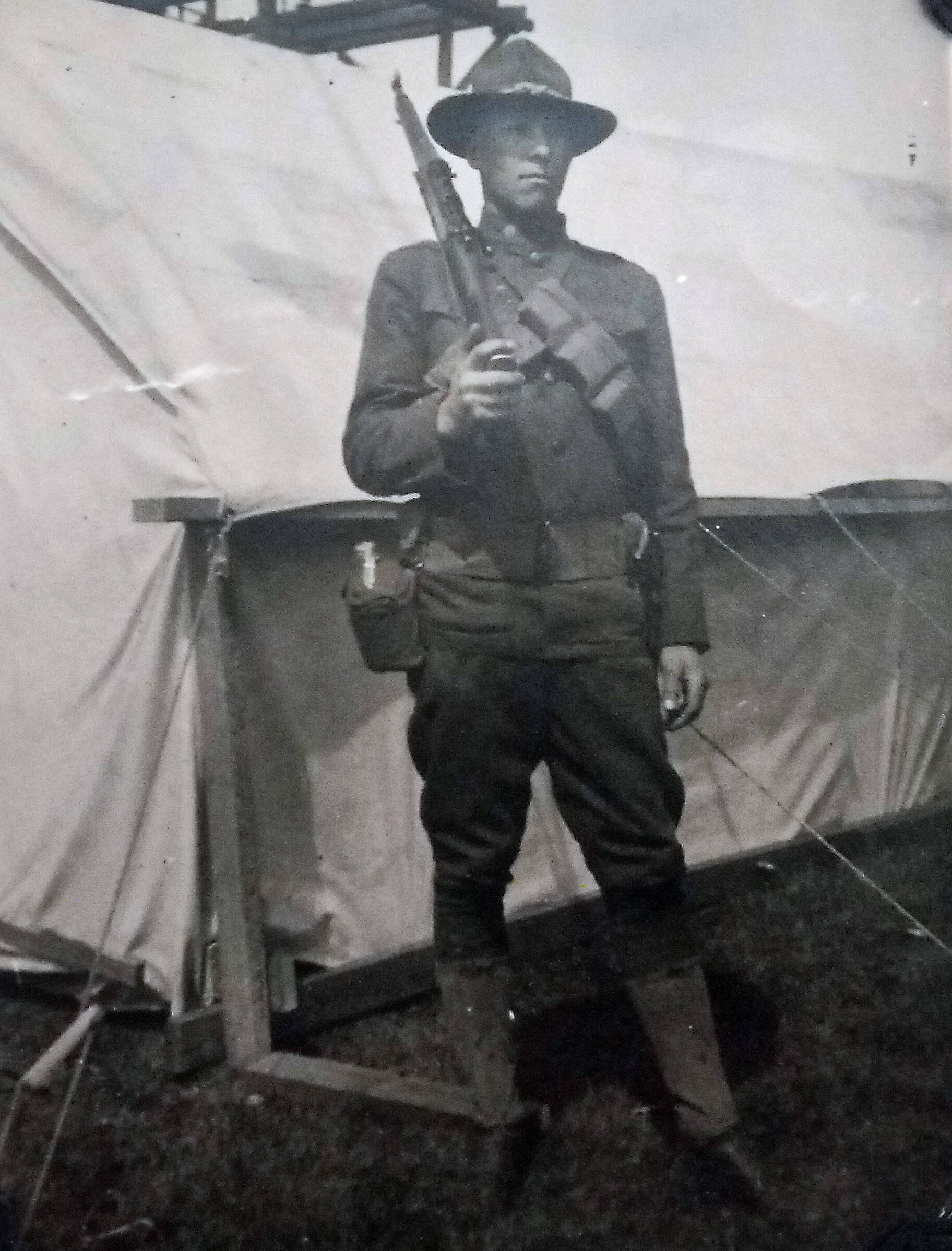

Floyd King grew into adolescence in Blackfoot and nearby Taber, Idaho. He played football at and graduated from Blackfoot High School. He enlisted in the military in the spring of 1917 and became a member of the Idaho National Guard in August. In November, he reported to Long Island, N.Y., for training and eventual inclusion in then-Maj. Douglas MacArthur’s brainchild for helping German-occupied France militarily — the Rainbow Division.

Rainbow was an elite division comprised of National Guard soldiers from across the country. After MacArthur was promoted to colonel, he was placed in charge of this composite force when it was given the designation 42 and, in the spring of 1918, was deployed in France. It became one of the most famous American fighting units in World War I.

Some of what Private (and later Corporal) Floyd King endured in France is known because he wrote letters home, and the Idaho Republican, the local newspaper in Blackfoot, reprinted three of them.

In a June letter, he advised his younger brother Bill to save his money. He also praised anti-German sentiment in Idaho. He said people were “beginning to realize that the American is a thoro soldier and not an ignorant rookie.” And he added that, while the enemy certainly offered some “hot entertainment … we are getting the best of it all the time.”

According to the other letters, he received mild injuries in mid-July 1918 and then more series injuries later, requiring a month and a half of hospitalization before he could rejoin his division.

He also related the horrors of war — attacks with poison gas; shell fragments and body parts on the battlefields; sleeping in water-filled ditches and fox holes — but he remained upbeat and proud of his accomplishments.

He also wondered what the future held once he was allowed to return home: “I don’t know just yet what I will do,” he wrote. “If I can get enough kale (money) together I am going into some small business in some live little western town. I am always going to live in the good old open west. I sure like the old west and I am longing for the good old days to come when I can go hunting and fishing once more.”

It seems likely that it was such sentiments that eventually drove him north to Alaska.

After more than a year in Europe — ending his service as a machine-gunner for Company A — Floyd King returned to Idaho in May 1919. His mother and sister met him in Taber to welcome him home.

His sister Mary got married that same month, and in August, Floyd, too, tied the knot in Arco, Butte County. He wed Ethel Anderson, one of the daughters in a large Mormon family.

Only a month later, Floyd’s 39-year-old mother, who had been suffering from a pelvic abscess, died on an operating table in a Salt Lake City hospital.

Devastated, Floyd’s father left Idaho in 1920 and moved to California with youngest son Omer. Floyd and Ethel were living in Arco at the time, near many members of her family. How their marriage ended, and when, is unknown. She remarried in 1929 and spent most of the remainder of her relatively short life in Montana.

The Idaho Republican, in August 1921, referred to Floyd King as a “former” Blackfoot resident now living in Pocatello.

After that, Floyd seemed to simply disappear from the record. His next certain appearance occurred nine years later and across the country. Despite his avowal to always live in the west, he was residing out east. Despite desiring “some live little western town,” he was a resident of a large city on the East Coast.

The Final Decade of John Floyd King

When Alec Hardin MacDonald completed his marriage certificate in 1943 in Fairbanks so he could wed Helen Irene O’Halloran, he lied about the number of times he had been previously married. He cited only Helen Mears as a prior spouse, stating falsely that he had married her in 1933 and divorced her in 1938.

In truth, MacDonald — in 1930, while still living under the name John Floyd King — had already set his sights on Miss Mears, a then-21-year-old divorcee residing in her parents’ home in Norfolk, Virginia.

When the 1930 U.S. Census was enumerated in Norfolk in April, Floyd King was also living with Helen’s parents, a dentist named Dr. James Lloyd Mears and his wife Judith. King was listed as a lodger, as a single man, and as a dental technician working in a dental laboratory. (Dental technicians specialize in building dentures, crowns, bridges and dental braces based on measurements and impressions provided by dentists.)

Whether King was also actually studying dentistry at this time is, despite the assertions in Ralph Soberg’s memoir, unknown.

Two and a half years later, King and Helen Adelia Mears were married. In an October 1932 notice in the Richmond (Virginia) Times-Dispatch, Dr. and Mrs. Mears announced their daughter’s betrothal to “Dr. John Floyd King.”

Despite the title granted him in the 1932 wedding announcement, Floyd was, according to a 1934 Norfolk city directory, still just a dental technician, laboring for United Dentists Inc.

In the 1940 U.S. Census, however, Alec Hardin MacDonald declared that on Oct. 1, 1934, he was living in Alaska. While it is possible for him to have lived in Virginia in the spring and in Alaska in the fall, the truth is murky.

What is more certain is this: John Floyd King, the dental technician, disappeared from the record sometime between 1934 and 1940, and Doc MacDonald came into being.