Shortly after midnight on Sept. 27, 1952, two prisoners sharing a cell at the federal jail in midtown Seward asked guard Donovan Wilson for an extra blanket. In order to comply, Wilson had to unlock and open the cell door, and that’s when they slugged him with a homemade blackjack consisting of a wrench tied in a sock and wrapped in a towel.

They tied Wilson’s hands and feet, and stole his keys. From the jail safe, the prisoners extracted about $250 in cash. They also broke into the firearms box and stole two pistols and several rounds of ammunition. After exiting the jail, they picked up some liquor at a nearby Seward store and then beat and kidnapped a driver for the Northern Cab Company and commandeered his cab.

Meanwhile, Wilson fairly quickly recovered from his knock on the skull and managed to loosen his bonds and sound the alarm. A multi-day manhunt soon commenced.

On the Run

The fugitives were Franklin Charles Oliver and Chester LeRoy Oughton. Both had been housed in the Seward jail while awaiting grand jury action on crimes they were alleged to have committed in the spring.

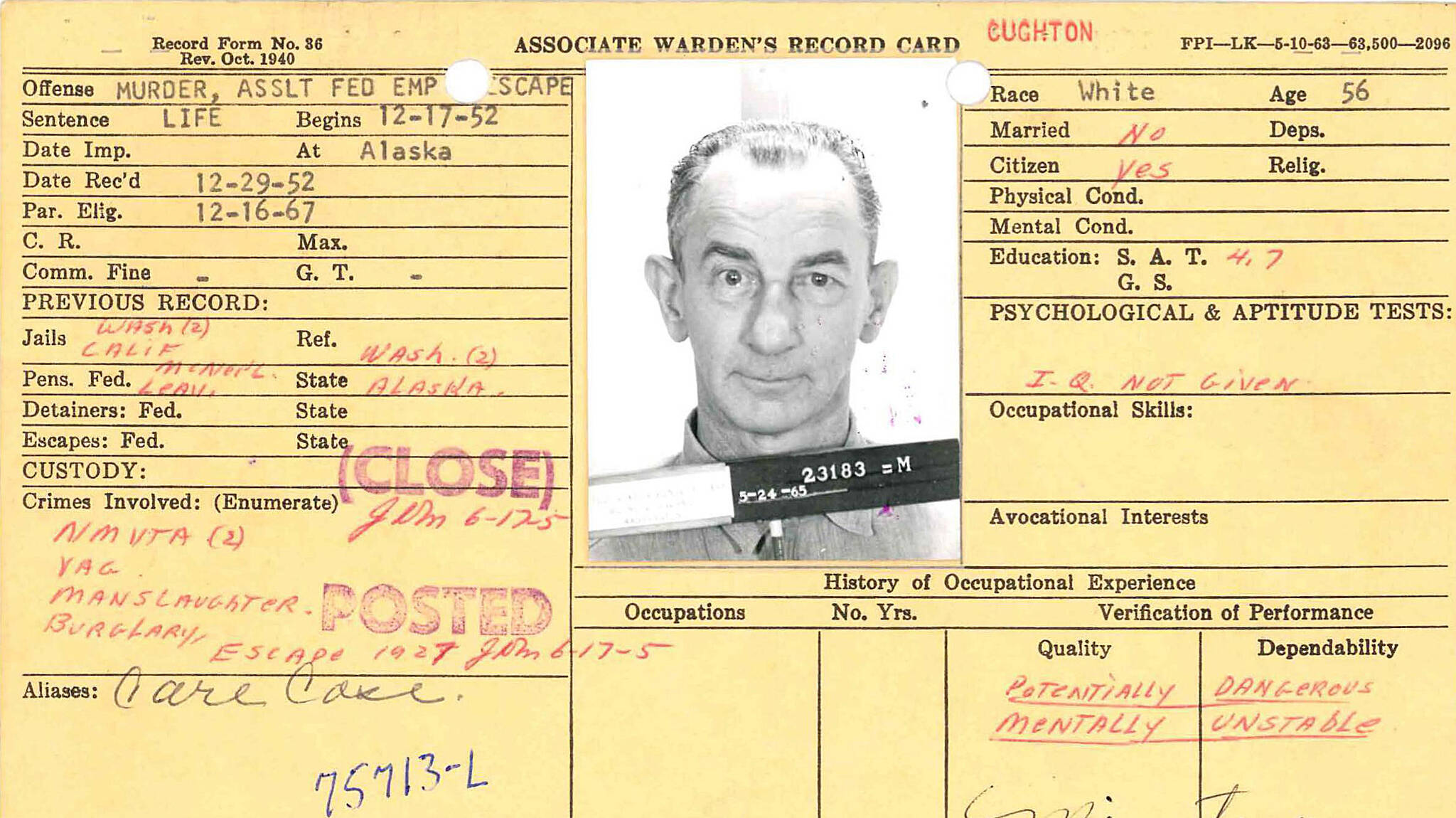

Of the two men, Oughton, 43, was considered more dangerous. He had a long rap sheet dating back to his teenage years in Washington, and after his most recent arrest, in Anchorage in April, he had been charged with first-degree murder.

By comparison, the 37-year-old Oliver was a minor criminal. He had been apprehended in Anchorage while attempting to sell stolen military weapons to undercover FBI agents.

Once the jailbreak was discovered, Deputy Marshal Irwin Metcalf in Seward called Martin “Harry” Soper, a café owner in Moose Pass, gave him a description of the stolen taxi , and instructed him to establish a roadblock.

When Soper and a companion saw the cab approaching — according to reports in the Anchorage Daily Times and the Seward Seaport Record — Soper fired two shots at the vehicle, but the fugitives were able to turn the car around and flee back down the highway toward Seward.

The kidnapped cabbie was still tied up in the backseat of his own vehicle. He reported later that he had overheard Oughton and Oliver scheming to drive to Kenai. With that plan foiled, he said, they drove, instead, to a cabin in the woods near the Trail River bridge at Mile 24 and holed up there for about two hours while deciding their next move.

Surrounded by mountains, swamps, streams and heavy brush, they abandoned the cab driver and his cab and headed further into the woods on foot. Eventually, the cabbie freed himself and drove back to Seward, arriving at about 5:30 a.m.

Additional roadblocks were established at Soldotna and Girdwood, at the Resurrection River bridge just outside of Seward, and at Mile 21, a pinch-point where the highway squeezed between upper Kenai Lake and some steep mountainsides.

Law enforcement officials alerted the public, issuing descriptions of the two fugitives and warnings to anyone living or driving between Seward and Moose Pass. Oughton was nearly 5-foot-8 and 150 pounds, with “brown wavy hair and a long hooked nose.” A tattoo on his right arm featured a one-inch heart with “C.O.” inside it. Oliver, who sometimes wore glasses, stood about 5-foot-9 and weighed 170 pounds, with a round face accentuated by a receding hairline.

A posse of about 50 authorities and volunteers searched the brush but found no campfires, no footprints and no clues to the prisoners’ whereabouts. As September became October, round-the-clock roadblocks were maintained at Moose Pass, Soldotna and Portage.

Criminal Action

Frank Charles Oliver was born in January 1918 in Dallas, Texas, and his life seemed generally unremarkable except for his military service and, of course, the arrest that had landed him in jail. If a 1952 Anchorage Daily Times article is correct, he first enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps in about 1938 and probably reenlisted several times. When he was arrested in 1952, he was serving as a cook for the U.S. Air Force at Elmendorf Field, near Anchorage.

On May 7, 1952, a Times headline blared “FBI Nabs 2 AF Cooks with 8 Machine Guns.” Privates Frank C. Oliver and Kenneth F. Pitman — both members of the 39th Food Service Squadron and both of whom had been AWOL for several days — had been taken into custody after attempting to sell submachine guns that had been stolen earlier from the Air Force base.

Undercover officers had met Oliver and Pitman in an Anchorage alley between Fourth and Fifth avenues and B and C streets. The two men had arrived in a taxi and were carrying a gunnysack containing the stolen weapons, which they offered for sale for $125 each — roughly 60 percent of their actual value. Shortly thereafter, they found themselves lodged in a federal jail in Anchorage.

Chester L. Oughton had already been in the same lock-up for about a month.

Oughton’s life of crime had begun early. He was only 17 in December 1925 when he pleaded guilty to burglarizing a pool hall in Lyman, Washington, and also admitted to car theft. He was sentenced to two to six years in the state reformatory in Monroe, Washington.

In early August 1927, he and fellow inmate John Dillingham escaped the reformatory and embarked on a brief crime spree. Within an hour of their escape, they had stolen a vehicle and were speeding through Everett on their way to Seattle. There, they assaulted and robbed a young couple, then fled in the couple’s car.

In late August, Oughton, under the alias Ray Smith, was arrested in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and charged with stealing vehicles and transporting them across state lines. In early October, one month shy of his 19th birthday, Oughton entered the federal penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas, as inmate #28379.

After his release from prison in October 1930, Oughton wasted little time being arrested again. Under the alias Charles Daly, he was charged by Seattle police with auto theft and in February 1931 was sentenced to one and a half to five years in the state prison at Walla Walla.

On parole in September 1933, he married Gladys Mae Hill. Five days later, he was arrested for violating the terms of his parole and was returned to the state prison. When he was released in March 1935, he was the father of one daughter.

Chester and Gladys had three more children, and for a number of years Chester appeared to go straight while moving from job to job. When he registered for the military draft in 1940, he reported that he was working for the Boeing Aircraft Company. A Seattle city directory in 1942 lists him as a janitor. He also worked as an independent house painter during this time.

But things went downhill for Chester Oughton soon after this.

In January 1944, he was arrested and briefly detained for “threats to family,” apparently his own.

He enlisted in the U.S. Army in February 1945, but was admitted to the military hospital at Fort Bliss, Texas, only five months later because of an injured knee. Hospital notes indicate that the knee problem was likely chronic, and he was quickly given a medical discharge.

Gladys divorced him in March 1946 and moved with their children to American Lake, Washington. In November 1948, he was arrested for vagrancy in Modesto, California, and jailed for 30 days. And in June 1949, he was arrested by Bellingham (Washington) police and charged with manslaughter.

Oughton admitted to striking a 45-year-old woman in her Seattle apartment in April; the woman never regained consciousness and died of the head wound almost two months later. Oughton was sentenced to one year in the King County jail and was released sometime in 1950.

In spring of 1951 he moved, alone, to Alaska.

After working briefly in Barrow, Seward and Anchorage, he was unemployed and living in a Mountain View cabin with a man named Jack Perlovich. In early April 1952, after staying in the cabin for only a few days, Oughton was arrested and charged with Perlovich’s murder.

The U.S. Marshal’s office in Anchorage called Oughton “a cold-blooded killer whose motive was profit.” According to charging documents, Oughton shot Perlovich in the back with the victim’s own rifle and then robbed the Perlovich premises. Although Oughton admitted doing the killing, he implied that he had done so in self-defense.

Six months later, in October 1952 in the Seward-Moose Pass area, the search for the fugitives went on.