AUTHOR’S NOTE: I first wrote about the Tustumena Lake cabin called Cliff House in 2009 for the Redoubt Reporter. After thoroughly researching the subject, I believed that I had most of the whole story. But I was wrong. About 10 years later, while working on a book project with historian Gary Titus, I learned there was more to the story, much more, including a possible murder.

So I did more research and some rewriting. Then in December 2021, I discovered more important twists to this tale. I decided, therefore, to start from scratch. Here, then, is the story of Cliff House, as least as I know it now.

Bob Huttle ponders history

The story begins with Larry S. Mikelsen, who grew up Washington state where, as a boy, he made the acquaintance a man named Robert S. “Bob” Huttle, a Hungarian immigrant (born Hüttl Rexsö) who had been a United States Marine and, later, chief of the Anchorage Police Department.

Huttle had also spent the winter of 1933-34 on Tustumena Lake, had photographed most of the people, structures and places he had experienced there, and, crucially, had kept a detailed daily diary of his experiences.

Huttle was new to the Tustumena area, and, frankly, he didn’t always get his facts straight. But he seemed to do the best he could. Americans and immigrants had been living and working on the lake for about four decades by the time Huttle began his sojourn there, and he was bound to scramble the history at times, especially since some of the people he encountered were also ignorant of the facts, despite what they may have proclaimed.

Fortunately for history lovers, when Larry Mikelsen became an adult, he gained access to Huttle’s diaries and decided to compile them, along with myriad Huttle photographs, into a book about Huttle’s life, including an episode at Cliff House.

One day in early April 1934 — as winter was contemplating giving a foot in the door to springtime — Bob Huttle ambled along the shore of upper Tustumena Lake and decided to spend the night in the then-vacant Cliff House. There, with a roaring woodstove warming the interior, he treated himself to a basic repast of sauerkraut with potatoes and onions and pot of boiled rice. Later, as the snow began to fall outdoors, he mused about the history of this place….

Exploding into history

I’ll return later to Bob Huttle and his musings.

Beforehand, it’s important to know this: Cliff House no longer exists.

Alaskans may be accustomed to the idea of fireworks on Independence Day, but in the summer of 1978 Miles Dean got a little more “bang for his buck” than he had bargained for.

The trouble had actually begun in June 1978, when John Swanson decided to install propane in his cabin called Cliff House on upper Tustumena Lake. Swanson, the owner of Peninsula Building Supply who in 1960 had become the newly incorporated City of Kenai’s first mayor, wanted gas-powered lights and a gas-powered cookstove in his cabin.

He got them, although the installation had not been error free.

According to Swanson’s son-in-law, David Letzring of Kasilof, Dave Donald boated up the lake in late June and discovered a leak in the fuel system. Donald turned off the valve on the propane tank and returned to Kenai to notify Swanson of the problem. A short time later, Letzring himself traveled up the lake with Swanson’s son, Ron, and they, too, tested the system and found it in need of repair.

According to testimony from Miles Dean himself, in a telephone conference with assistant Kenai National Moose Range manager Bob Richey, Dean and his wife had arrived at Cliff House late on July 2. He had disconnected a large, empty propane canister and hooked up a smaller, fuller canister. He also noted that someone had recently installed a newer woodstove in the cabin.

The following morning, after eating breakfast and washing dishes, the Deans left a dying fire in the woodstove and went boating north along the lakeshore. Shortly thereafter, they observed smoke in the vicinity of Cliff House and returned to find the cabin incinerated.

“The Cliff House ceased to exist,” said Letzring. “The metal roof was almost to the glacial flat. Pieces of the place were in the lake. It was all over. There was nothing left. It blew up … just like a little bomb.”

In addition to the cabin itself, the Deans lost numerous personal items, including a camera lens, a chainsaw, rubber boots and sleeping bags. When Bob Richey visited the site on July 5, he found Miles Dean’s assessment accurate. Cliff House was gone.

With its destruction went a piece of Kenai Peninsula history, possibly dating back as far as 1910.

Evolution of Cliff House

Both Gary Titus, a former historian for the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge, and George Pollard, who had lived in the Tustumena area since the late 1930s, agreed that the original builder of Cliff House was August “Gust” Ness. The first known historical mention of the structure can be found in a 1921 entry in the diary of big-game guide Andrew Berg, who lived on Tustumena Lake throughout the early 1900s.

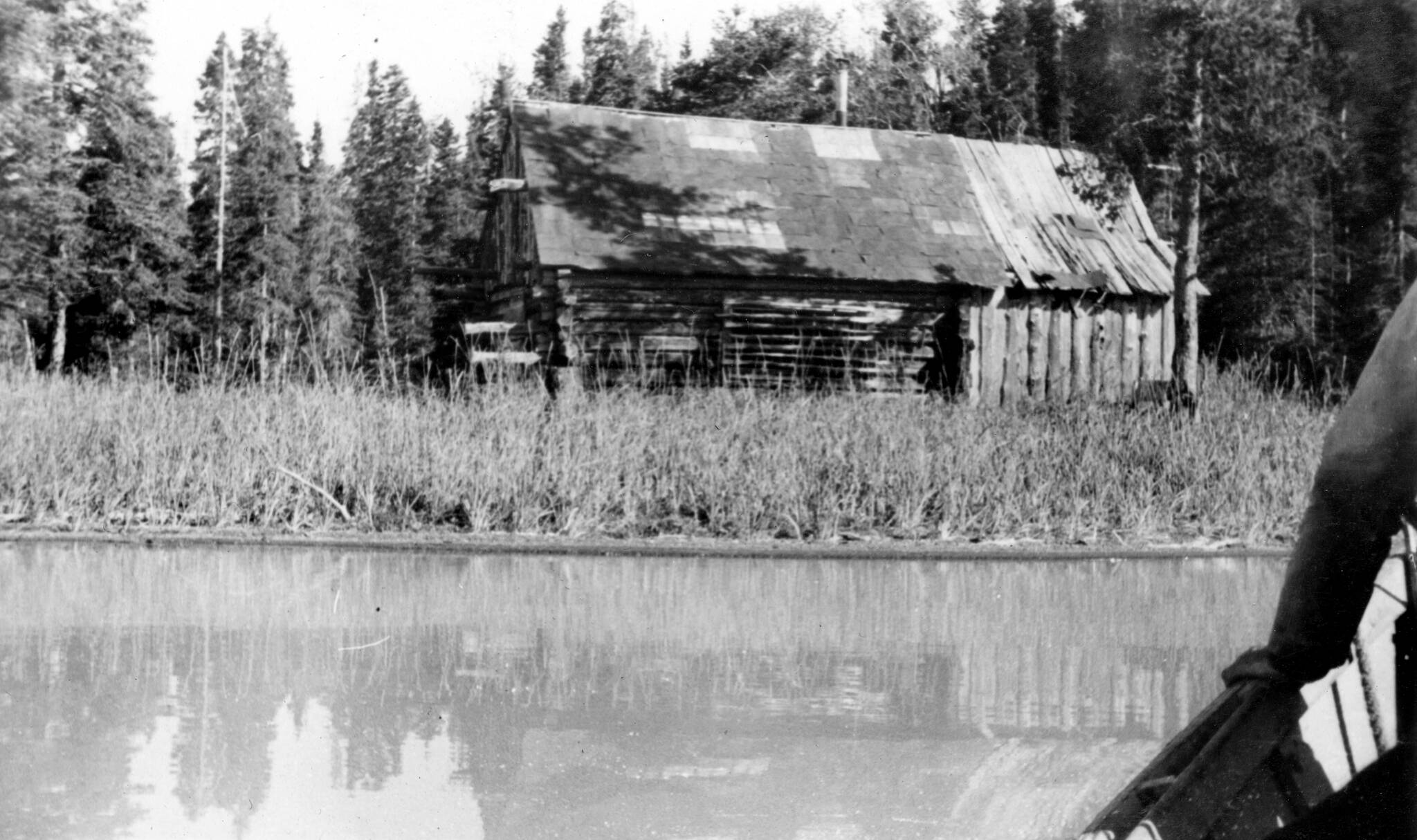

Ness selected an ideal location for his log structure: near the back end of Devils Bay, on a small point of sandy land just below a set of cliffs that inspired the name of the cabin and provided shelter from winds rushing down the outwash plain of nearby Tustumena Glacier and the Harding Icefield. Protected also by a stand of spruce along its northern and eastern sides, the cabin was a safe haven in nearly all bad weather. According to Pollard, it was vulnerable only to a strong wind out of the southwest.

The cabin door faced roughly west toward the cliffs, near the entrance of a trail to the glacier. The picture window faced south, and Pollard recalled sitting at the table by the window to watch brown bears feeding on spawning sockeye in Clear Creek less than a quarter-mile away.

By the 1960s, Swanson had installed a new steep metal roof, with a long gable over the front porch, to provide protection from summer rains and more easily shed heavy winter snows. For insulation, in the open, empty space between roof and ceiling boards, he dumped loads of beach sand. Letzring recalled that after a night in Cliff House, he needed to brush off his sleeping bag because sand continually sifted through the boards above his bed.

By the 1970s, one exterior wall had been draped with several sets of moose antlers. Another wall, too, featured an array of trophies, including at least two bear hides.

When Ness died of a heart attack in 1937, the cabin passed into the possession of Gust’s step-son, Tony Johansen. According to “Alaska’s No. 1 Guide” by Titus and Catherine Cassidy, Johansen was the son of Mary (Demidoff) Ness via his mother’s first marriage to Fred Johansen.

Tony Johansen hung onto Cliff House until 1951, the year (according to U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service records) that Swanson reported buying the cabin.

When Tustumena Lake passed from being part of the Chugach National Forest to being part of the Kenai National Moose Range in 1941, no new cabin construction was allowed on refuge land (except within private inholdings). Many of the numerous old cabins on the lake fell into disrepair or became temporary shelters for hunters traveling into the hills for big game.

Gold miner Joe Secora, who owned a 5-acre inholding on the north shore, was the last of the numerous old-timers who once could be found living seasonally or year-round on the lake. His death in a 1972 plane crash signaled the end of an era.