By Clark Fair

and Rinantonio Viani

AUTHORIAL NOTE: Part One introduced a former Kenai resident named Peter F. “Frenchy” Vian, and the attempt to tell his story by Clark Fair in Alaska and Rinantonio Viani in Switzerland. Parts Two and Three revealed Frenchy’s real name and heritage and some of the family dynamics that likely spurred him to adventure in Alaska. They also related the results of a Bering Sea polar bear expedition and a sailing mishap in 1892.

Having a Good Tale to Tell

On Oct. 25, 1892 — on stationery bearing the heading “Snyder Hough Co. Wholesale Fish Dealers and General Commission Merchants, San Francisco, Cal. Alaska Branch, Sand Point, Humboldt Harbor” — Frenchy Vian penned a letter to his Uncle Nicola back in Calumet, Michigan, to relate the wild details of his previous 20 months … and to ask for some money.

He began with: “I don’t know if the Devil put his horns between me and luck because after I am in these parts I am not spared neither fatigue nor cold. A very bad life and I have exposed myself to peril of my skin millions of times against wild beasts, and do you know what a state I am in? I am penniless.”

Then, through colorful detail and exaggeration, he spun a yarn designed to elicit financial assistance from Nicola.

He believed his uncle already knew the polar bear part of the story because it had been in national newspapers, so he concentrated on the more recent Sand Point saga — the “terrible storm,” the shipwreck, the money he owed for the lost vessel, the 500 miles of travel (twice as far as he’d told newspapers) he had made “over high mountains covered with ice and snow in the month of October,” sleeping in a wet blanket — kept alive only by the heat from his sled dogs — and the emptiness of a belly desperate for nourishment.

If Nicola would only lend him enough money to begin to pay his mounting debts, he said, he felt certain he could find ways to make even more money and to pay Nicola back twice over within 18 months.

Nearly a year later, an article about Frenchy’s adventures appeared in a San Francisco newspaper, containing greater detail, some of it clearly exaggerated — perhaps by Frenchy himself. The article implied, for instance, that the polar bear-hunting expedition on St. Matthew Island may have been a cover-up for the real purpose of going there: a search for the “fabled gold fields” discovered by the crew of a previous ship 30 years earlier.

While relating his St. Matthew adventures to the members of an Indianapolis hunting club in 1904, however, Frenchy focused on polar bears, claiming to have employed a canoe to hunt them as they swam in the Bering Sea.

“They are splendid swimmers and can dive like ducks,” he told eager listeners, according to newspaper reports. “On several occasions I got close to them, and when they grabbed the end of my rifle I put a shot through their heads.”

He also told a hilariously over-the-top tale of live-capturing a polar bear: “I saw a big fellow swimming in the sea and paddled close to him. Giving the canoe a sharp turn, I came alongside the bear and lassoed him with the anchor rope. The bear was frightened and swam at great speed, dragging the canoe through the water.

“I sat in the stern steering with my paddle. The bear swam for three or four hours and then made for the land. My man and I were ready for him, and before he touched bottom we threw our canvas tent over his head. While he fought to disentangle himself, we wrapped him in the boat’s sail and more rope. I then got astraddle of him and, putting a rope around his mouth, twisted it tight with a stick and so had him.”

Frenchy, said the article, put a ring in the bear’s nose and kept him at camp, but the bear proved to be a “dangerous pet, jumping at his captor the full length of his chain.” So the bear was “disposed of.” And that was just one of 24 polar bears Frenchy claimed to have killed in a single year.

Measuring Success

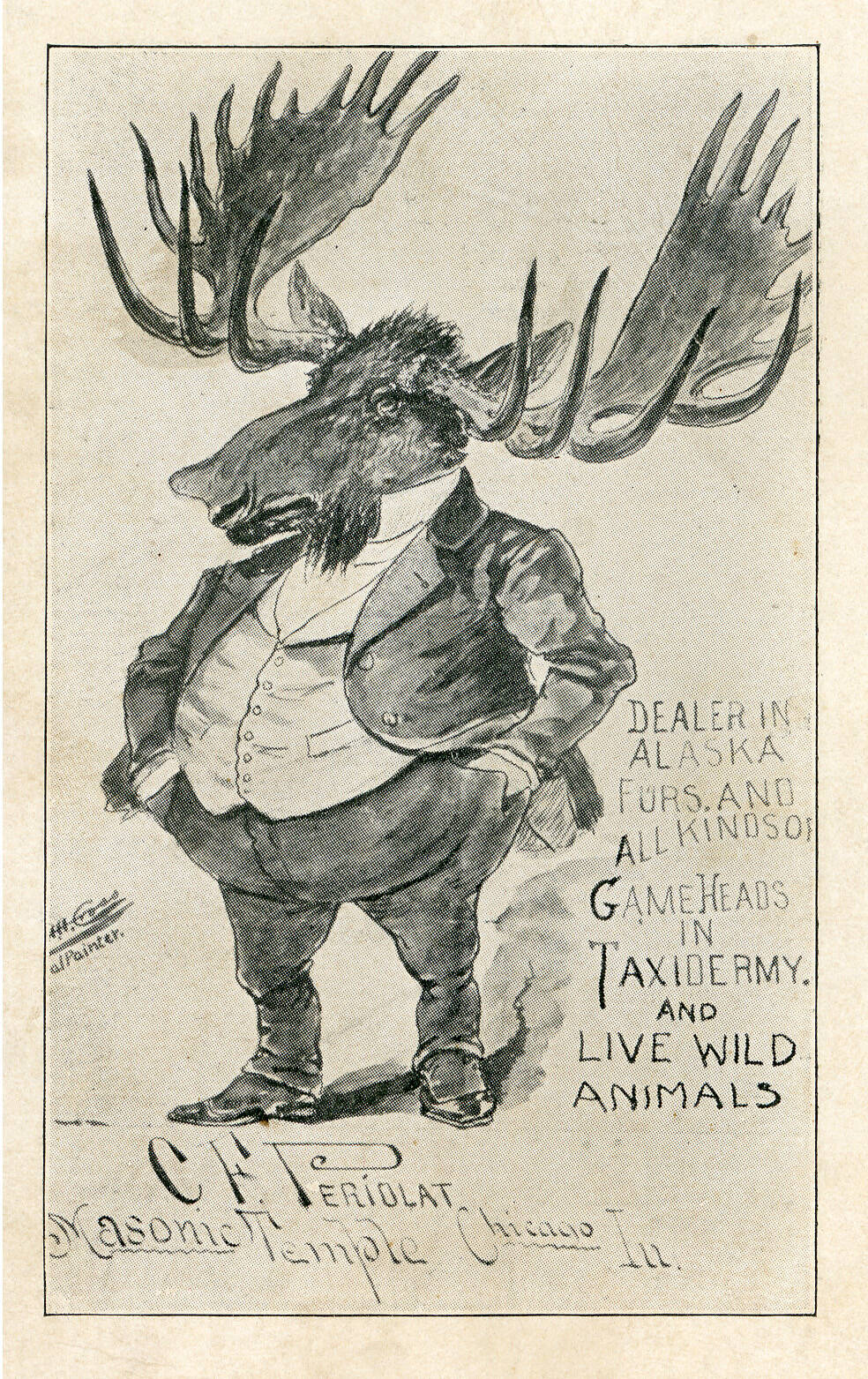

Frenchy had stopped at the Indianapolis hunting club mainly to see “old friends,” Jesse Fletcher and Harry S. New (a friend of Teddy Roosevelt and future U.S. Postmaster General). He had befriended the two men while acting as their guide on a moose-hunting trip in the Tustumena Lake area in the fall of 1902. When he made his Indianapolis visit, he saw that one of the walls at the hunting club had been adorned with a mounted moose head from a kill made by Fletcher on that Alaska trip.

The Indianapolis News, which covered the hunting club event, stated that Frenchy was “one of the best guides [to be found] throughout Alaska.” Certainly, Frenchy himself did little or nothing to quiet the praise. (Before 1908 in Alaska, guides were not required to be licensed, and there was no mechanism in place to allow the government of Alaska to hire its own game wardens.)

Photos of Frenchy taken just a few years earlier portray him as a very capable hunter and a gatherer of impressive trophies. In one image, his hunting rifle leans against a tree while he holds a freshly dispatched black bear to show off its size.

In another, a mustachioed Frenchy reclines on a porch in Kenai, his legs stretched across a large set of moose antlers, while a sled dog hunches at his feet.

The most impressive of these early shots — also taken in Kenai — shows Frenchy and his dog among a huge jumble of hunting and trapping trophies. Luxurious-looking furs hang from a back wall. Moose antlers and sheep horns are piled nearby with a pair of snowshoes. Also, what appears to be a mounted bear is rearing up in the background.

Some of these trophies Frenchy may have purchased in his role as trader in Kenai, but the point of the image seems clear: Despite having had only two and a half years of formal education in Italy, il Bandito was a success in America. Only a few short years after asking his uncle for money while he was stranded in Sand Point — after promising he would succeed, if only given an opportunity — he had been true to his word.

But Frenchy was not satisfied. Not yet. And he was also not even close to being finished with big achievements.

In a letter to his youngest brother, Carlo, more than a decade later, he wrote: “A man must have a aim in this wide world, and if a man don’t go ahead, he goes back. And if I was young like you I would learn many many thing. If I had a brother when I was your age to tell me what I been telling you today, I would be a great man, or if I was only of your age [now] I would do some big thing that would open your eye.”

When he wrote those words in 1918, he was a success by many measures. He owned property, had made investments, was a partner in mining operations, traveled widely and often, and could buy what he wanted when he wanted it. Truly, he had little, or nothing, left to prove.

His life was not perfect, however, as he revealed sometimes in letters to family. Although he complained to his parents about what he perceived as their lack of appreciation of his success, he clearly missed his home and family in Italy. He also was tiring of the hectic nature of life in America; he felt more and more ready to settle down.