By Clark Fair

and Rinantonio Viani

AUTHORIAL NOTE: Part One introduced a former Kenai resident named Peter F. “Frenchy” Vian, and the attempt to tell his story by Clark Fair in Alaska and Rinantonio Viani in Switzerland. The next four installments revealed Frenchy’s true heritage and the extent of his success in Alaska. They also demonstrated that Frenchy, in his 40s and 50s, strongly missed home and family back in Italy. But the war disrupted his plans.

Homeward Bound

The following brief notice appeared in the Anchorage Daily Times on June 2, 1917: “’Frenchy’ Vian, old timer of Kenai, has sold his store to William Dawson, another sourdough, and has departed for the states.”

This divestiture signaled the departure of Peter F. “Frenchy” Vian from Alaska and, for those who knew him, his intention, as soon as possible, to finally leave the United States and return to Italy.

“I would gladly come to pay you a visit,” he wrote to his mother six months later, “but as long as there is a war, I cannot come.”

“We here are sure that we will win the war,” he wrote to his sister Bianca. “We have everything we need, men, money, ammunition, ships—in the end everything we need in war. I would pay a lot if I were younger to enter the war as a flyer…. I applied for a [military] job here, but they wouldn’t take me, saying I was too old….

“If I couldn’t go in as an Airman, maybe I could in as a captain of the steamers that hunt the submarines. You don’t have many men there, and maybe they would take an old man like me.” Two months later, perhaps with that in mind, Frenchy earned a Seaman’s Certificate of American Citizenship from the U.S. shipping commissioner at Seattle.

In March 1918, as the war began to wind down, he sought a favor from his father but couldn’t resist simultaneously directing some sarcasm at the old man. In a letter typed in all caps, he wrote: “Dear Father, maybe your eyesight is not so good, so I thought of writing large words. I would be very pleased to receive a letter written by you, or tell me the reason you don’t want to write….

“Could [you] give me an idea if there are any of those villas between Oneglia and Porto Maurizio for sale and how much they want,” he continued. “I’d wish to buy one. I want to come home, and I would like a nice house…. I hope that soon this war will be over and then I will be able to see you and maybe catch a few more eels and birds and thrushes.”

Meanwhile, Frenchy sent money home to struggling family members, who weren’t always prompt enough to satisfy him in acknowledging the receipt of these payments. Even after the war ended in November 1918, the replies returned too slowly to suit him. His patience was wearing thin.

“Dear Parents,” he wrote in November 1919, “I still do not know if you have received the money that I sent you in February. Perhaps you wrote to me in Wenatchee [Washington] and I did not receive it, but I believe that if you had sent it immediately as it is your duty to do I would still have been there and would have received your much desired letter, instead of always [wondering] for the past 8 months if you have received the money or it is lost.

“I am very sorry to say this,” he went on, “but your brain is dead, and if it is not dead, it is dying.” In the same letter, he offered to buy some land from his father.

He also wrote to his brother Giuseppe to remind him that three months earlier he had sent him bank drafts totaling nearly 45,000 lire so Giuseppe could buy government bonds for him.

Finally, in March 1920, Frenchy left the United States and returned home. He did not relinquish his legal residence in the United States, but he remained in Imperia for the next two years before traveling again.

Happy at last, but not for long

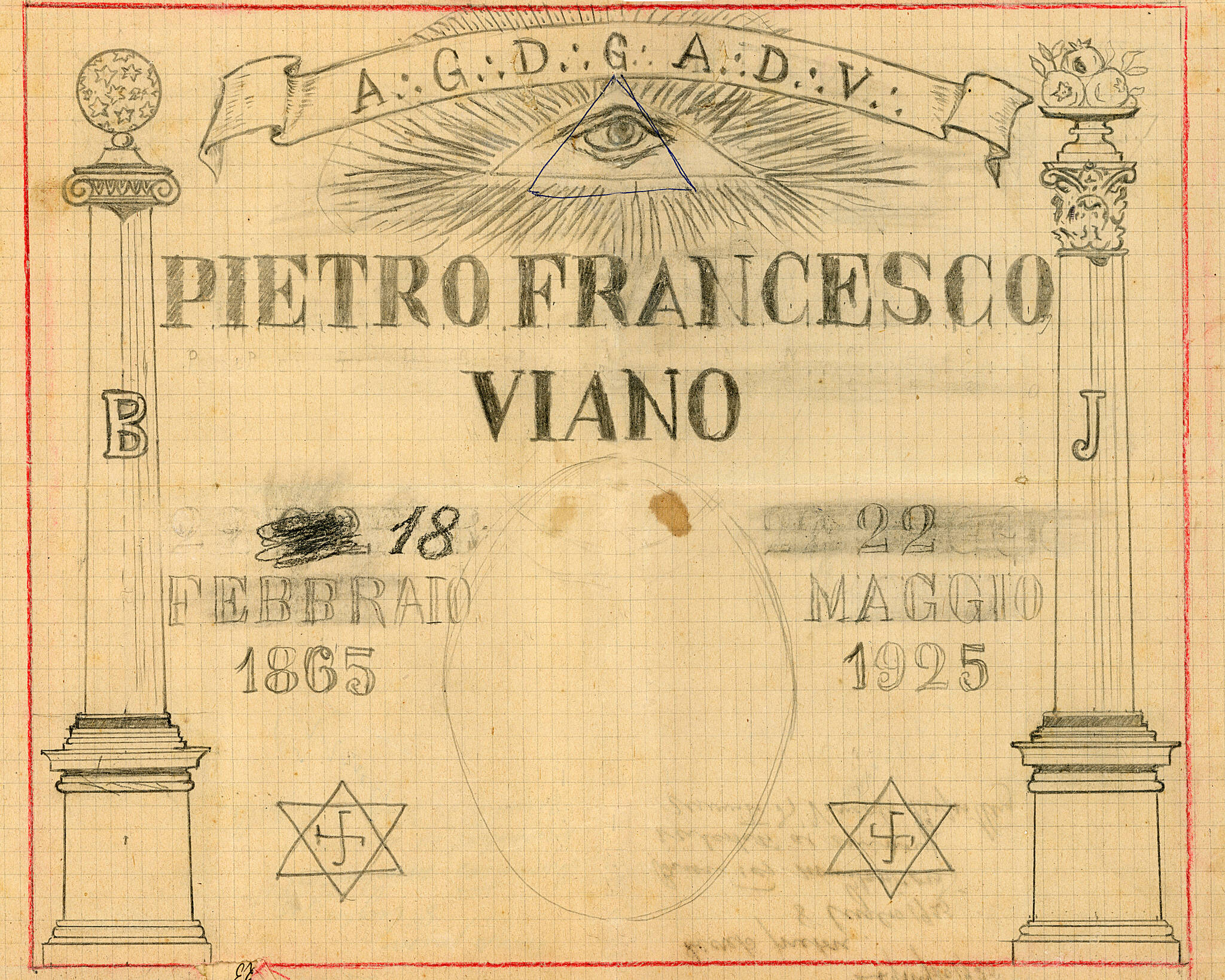

According to Filippo Bruno’s 2011 book on Freemasons of the Imperia region of Italy, Frenchy had become a Freemason in the United States on May 29, 1890, reaching 32nd grade in 1908. After his death at age 60 in May 1925, his nephew Giò Viani designed a tomb for Frenchy containing traditional Masonic symbols.

The name on the tomb was Pietro Francesco Viano.

Born Pietro Francesco Viani in Italy, transformed by his own hand into a Frenchman named Peter F. Vian in the United States, he opted for another change in his final years back in the land of his birth.

He also got the land he wanted and built the home he wanted. He even got, at long last, the family that he had desired.

At some point between 1922 and 1924, Frenchy Viano — labeled benestante (“wealthy”) by government officials at the time of his repatriation — married his housekeeper, a woman named Angela Strafforello, 35 years his junior.

On Dec. 27, 1924, Angela gave birth to Frenchy’s first and only child, a son whom they named Everest Viano. About five months later, Frenchy succumbed to cancer, leaving young Everest to with no memory of his father.

When he was 35, however, Everest and his own wife produced their only child, a daughter they called Manola, who became the caretaker of her grandfather’s old letters and photographs.

And thus it was — once Rinantonio Viani discovered Manola’s existence in 2021 — that many vital chapters in the story of Frenchy fell into place.

Rendezvous in Lausanne

The family members of Clark’s partner, Yvonne, all live in Switzerland, and, until the pandemic struck in 2020, Clark and Yvonne had visited there regularly. When 2022 rolled around, it had been three years since their last trip abroad. By this time, Clark and Rino had been corresponding for months and had been talking about co-authoring Frenchy’s story.

Clark decided to carve out a couple of vacation days to ride a bullet train to finally meet Rino face to face and to strategize at Rino’s home near the shore of Lake Geneva. From der Bahnhof in Zurich to la gare in Lausanne took about three hours, and he and Yvonne stepped from the train into the sunshine, nearly missing Rino in the bustle of this transportation hub.

While Yvonne busied herself with a walkabout in Lausanne, Clark and Rino spent the afternoon in Rino’s book-lined home office, comparing notes, sharing information, and planning the basic narrative of the story they hoped to tell.

They acknowledged that certain pieces of the Frenchy puzzle still were missing, but they knew that together they had assembled an interesting, coherent tale.

Near where Rino had been born in 1933, Frenchy had been born in 1865. Near where Clark had lived nearly all his life, Frenchy had come to live and had thrived. Now, Rino and Clark had united to bring Frenchy’s tale full circle.