Three-and-a-half steps.

Visualize it: that’s how big your home is. Back against the wall, three-and-a-half steps until you can’t go anymore. Arms straight out at your sides, fingers touching both walls, cement floors. Hardly a palace.

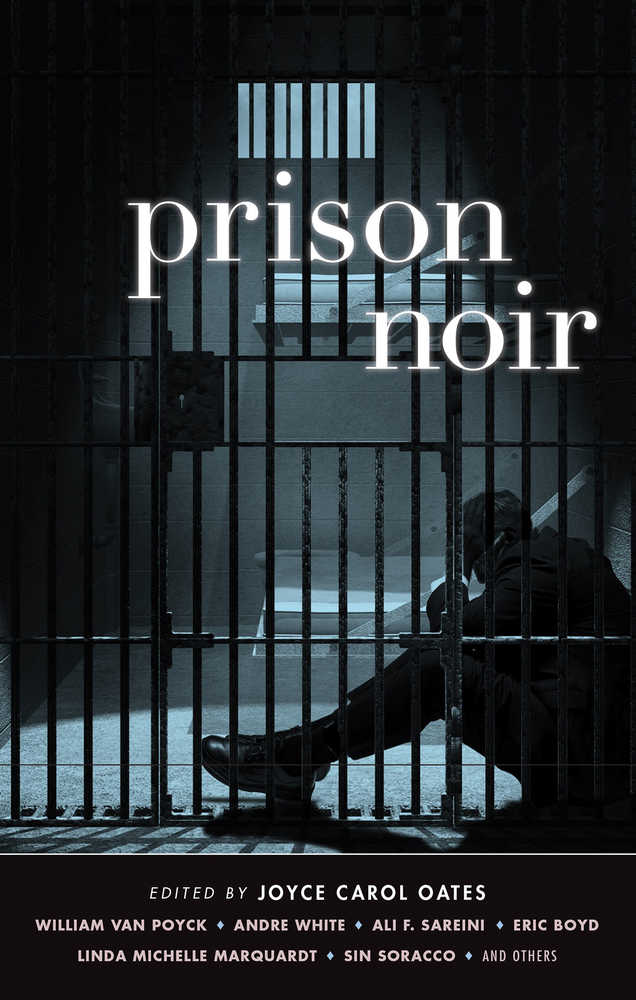

Now you head outside any time you want, day or night, to do what you want to do. But picture bars on your doors and someone telling you when to eat and when to sleep. Then grab the new book “Prison Noir,” edited by Joyce Carol Oates, and read other tales of doing time.

Imagine the difficulty of choosing the best fifteen of a hundred exceptional prison stories, a challenge that faced author-editor Joyce Carol Oates in pulling this book together. That the entries she read were “well-crafted” should be no surprise; after all, each of them was written by someone who is or has been in prison, which lends a “disconcerting ring of authenticity” to tales like these.

You know if you’ve been incarcerated, for instance, that having cellies can be a thorny issue, but in the first story, “Shuffle” by Christopher M. Stephen, even segregation doesn’t mean “true solitary confinement” anymore.

Yes, roommates and block mates can be trouble – but they can also keep a person sane, as in “I Saw an Angel” by Sin Soracco. Conversely, as in “Bardos” by Scott Gutches, the person two cells down can make you really think – especially when he’s dead just shy of his release date.

In prison, there is no privacy. There is no escaping the sound of the echoing clink of “hundreds of doors closing at the same time.” There can be language barriers that lead to huge misunderstandings. In prison, as in “Milk and Tea” by Linda Michelle Marquardt, there are people just trying to get by and get beyond a crime that surprised even them. And behind bars, there’s danger – not just to others but, as in “There Will Be Seeds for Next Year” by Zeke Caliguiri, there’s danger to the inmate himself…

In her introduction, Joyce Carol Oates says that there were some stories in this anthology that she read multiple times, and she admits that there were others she didn’t quite understand. She calls them “… stark, somber, emotionally driven… raw, crude, and disturbing material…”

And she’s right. But she forgot the word “riveting.”

Indeed, it’s hard to turn away from what you’ll read inside “Prison Noir.” There’s sadness here, frustration, resignation, and a surprising sense of slyness. You’ll find fiction, perhaps, or maybe it’s all real – possibilities of which you’ll squirmingly have to remind yourself. Either way, the fifteen contributing authors didn’t seem to be holding anything back which, for the right reader, can be some powerful seat-glue.

Beware, before you pick up this book, that it’s filled with exactly what you’d expect from prison literature. I enjoyed it quite a bit, but I wouldn’t begin to call it nice. With that caveat in mind, I think that no matter what side of the bars you live on, “Prison Noir” is worth doing time with.

The Bookworm is Terri Schlichenmeyer. Email her at bookwormsez@gmail.com.