By Clark Fair

For the Peninsula Clarion

In 1960, my father, Dr. Calvin M. Fair, was nearing the end of his three-year stint as a dentist for the U.S. Army and had decided to begin his own private dental practice in Southcentral Alaska. To best determine where to set up shop, he gathered names and addresses of dentists and chambers of commerce in the region and began writing a series of letters.

On April 15, longtime Seward resident Luella James, whom my parents had befriended in the late 1950s, sent my father a typewritten letter to encourage him to consider living and practicing in Seward. At the time, Seward was home to Dr. Russell M. Wagner, the only full-time dentist on the entire Kenai Peninsula. Luella didn’t see that as a problem.

She wrote: “I believe there can be no doubt that there is need for another dentist here as appointments are being made for three months or more in the future…. I have been told that Dr. Wagner … does not plan to practice long. He is a very competent man, but he had a bout with polio a few years ago, and has never fully recovered…. His wife has seemed to indicate that he contemplates an early retirement. We feel you would be busy and happy here.”

On April 21, Dad wrote to Dr. Wagner to tactfully inquire into the prospects of work in the Gateway City. On April 29, Dr. Wagner responded with four typed half-sheets of paper and a hand-drawn map of communities of the Kenai. He made no mention of pending retirement and was hardly encouraging about Dad’s prospects in Seward:

“The 5,000 population figure that the [Chamber of Commerce] gave you would include most of the Kenai Peninsula. The Seward area proper has nowhere near that number of people…. At the present time, I am the only full-time dentist in this area. From time to time a dentist from Anchorage comes down and does some work for people both at Kenai and Homer. The balance of the time, the people over there are dependent upon Seward and Anchorage for their dental work.”

If nothing were to change, Wagner asserted, two dentists in Seward “would do O.K.” Then he predicted that Soldotna or Kenai would soon be getting a full-time dentist. “When this happens,” Wagner wrote, “he will get most of the people over there. This would leave only the Seward area proper, which would hardly support two men.”

Wagner did, however, plant a seed of optimism: “For the past couple of years, some of the big oil companies have been test drilling and it appears that now they have a developed a producing field. So from an economic standpoint, conditions look good and there is starting to be an influx of new people.” He urged my father to look to the central peninsula, instead of Seward, for his opportunity.

Dad took Wagner’s advice. We moved to Soldotna on Oct. 3, 1960, and Dad practiced dentistry there for nearly 40 years.

In retirement, my father assembled a detailed “dental career” scrapbook, including correspondence from and notes about Dr. Wagner. After examining all those words, I began to wonder about the man who was Seward’s lone dental ranger. What kind of man, and what kind of dentist, had he been?

The answer turned out to be complicated.

In his notes my father wrote that Wagner “did not want me here and would not even talk to me.” I’m uncertain whether the two men ever met face to face, but Wagner seemed cordial enough in his letters. He ended the April letter with: “If you have any further questions, I shall be happy to try to answer them.” And in a November missive about dental finances, he concluded: “I shall be glad to help you in any way that I can.”

Why then, I wondered, had Dad been so sour on Wagner when the Seward dentist had seemed amicable enough and had simply been forthright about the situation in Seward?

After Dad died in early 2007, I asked my mother what she remembered. Mom seemed baffled by Dad’s mild disdain, and she could recall almost no specifics about Dad’s interactions with Wagner.

So I began a more general search for information. The bits and pieces I have uncovered over the years paint an incomplete picture, but they do help clarify why the Seward dentist is not easily characterized.

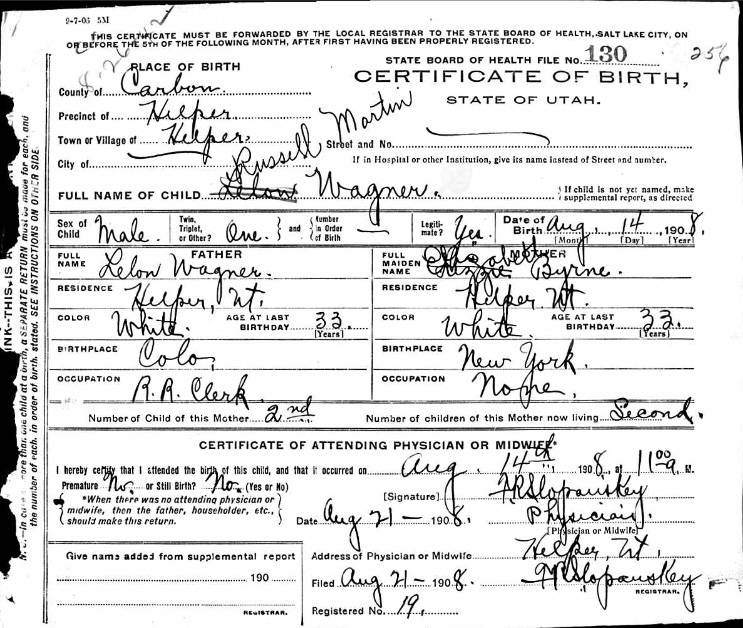

Russell Martin Wagner was born Aug. 14, 1908, in the small railroad town of Helper in Carbon County, Utah. His father was 33-year-old Lelon Wagner, a Colorado-born railroad clerk. Russell’s mother was 33-year-old, New York-born Elizabeth “Lizzy” (Byrne) Wagner. They had one other child, a daughter, nine years older than Russell.

In 1910, the Wagners were in Colorado, and Lelon was still a railroad clerk. By 1930, they were in San Francisco, Lelon was a railroad accountant, and the family had added another daughter and another son. Russell, a 21-year-old graduate of Mission High School (in San Francisco) at the time of the U.S. Census, was still living with his parents.

Wagner graduated from dental school at the College of Physicians and Surgeons in San Francisco on May 15, 1931, and by 1933 was listed in San Francisco city directories as a dentist.

Shortly after graduation and before beginning his dental practice — probably in the summer of 1931 — he traveled to Seward to visit his older sister, Katherine (wife of banker Harry Balderston). His visit coincided with the decision of Dr. Avery Roberts, one of Seward’s two dentists at the time, to take a sabbatical.

According to “Unga Island Girl: Ruth’s Book,” by Jacquelin Ruth Benson Pels, “Dr. Wagner cared for Dr. Roberts’ patients in the month or two he was gone…. When Dr. Roberts made a permanent move to Kodiak, Dr. Wagner came back and took over the practice in Seward.” Pels’ mother, Ruth, worked as Wagner’s assistant, just as she had done for Dr. Roberts before his departure.

On April 2, 1934, Wagner opened his own practice on the corner of Fourth Avenue and Adams Street. With Dr. Roberts’ departure, Seward remained a two-dentist town, although the community briefly had three dentists in the early 1940s.

Dr. Wagner’s tenure in Seward went on to include definite highs (a certain teacher of home economics) and dismal lows (a polio outbreak), and in the end not everyone would agree with either Luella James’s praise of Wagner’s competence or with my father’s scorn — as will be seen in Part Two.