By James Brooks

Alaska Beacon

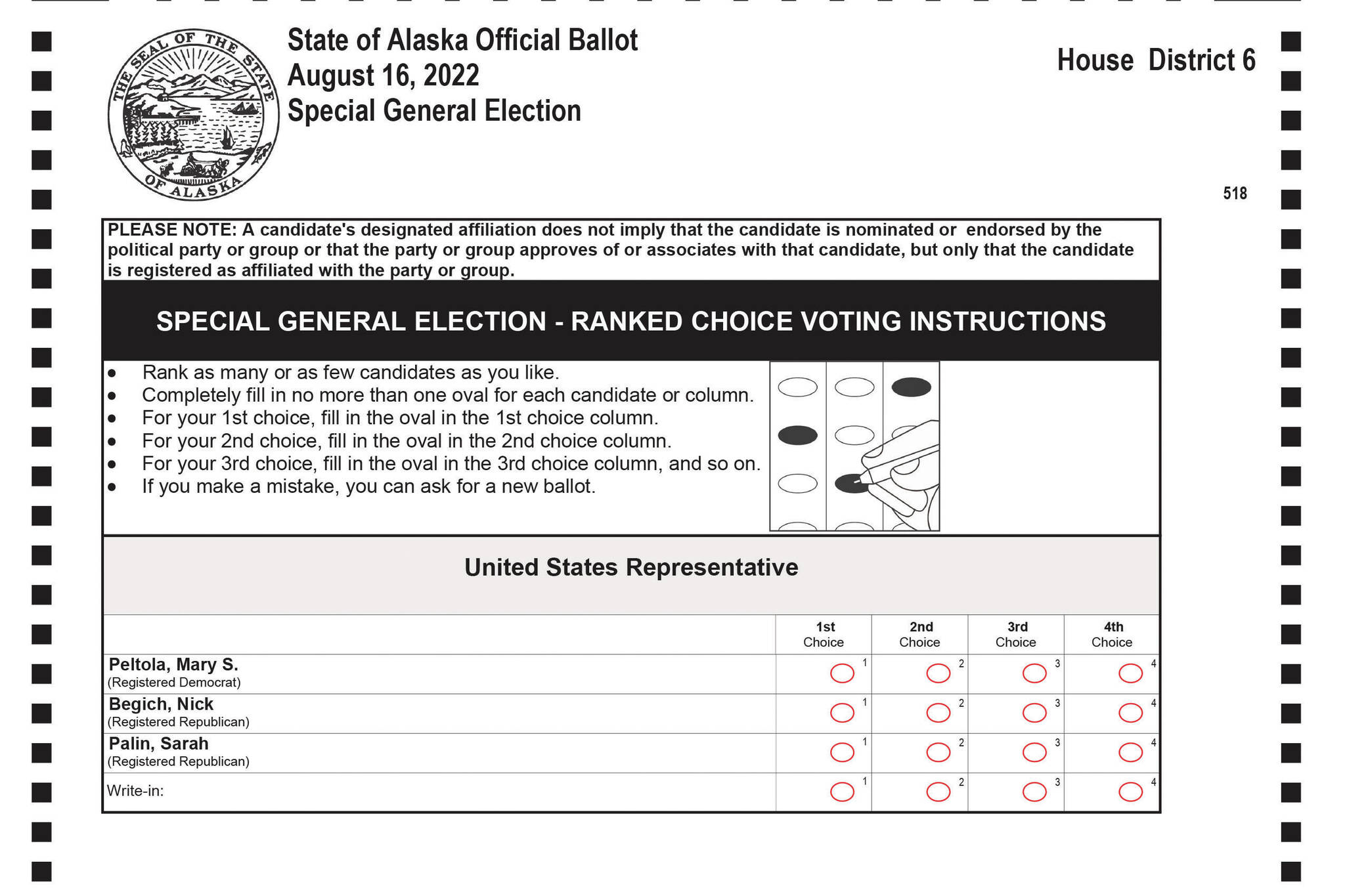

The Alaska Division of Elections on Friday certified the state’s Aug. 16 special general election for U.S. House, confirming Democrat Mary Peltola as the winner.

Peltola will be sworn in as Alaska’s lone U.S. representative later this month after defeating Republican candidates Sarah Palin and Nick Begich III.

Though elections officials are still compiling statistics from the vote, political advisers, pollers and independent observers say there are five early lessons from Alaska’s first ranked choice election:

Ranked choice voting mostly worked

In results shared by the Division of Elections only 295 people cast ballots that couldn’t be counted for at least one candidate, including write-ins. That’s less than 0.2% of all votes.

This figure represents only “overvotes,” ballots with marks that couldn’t be counted. Some people also cast blank ballots.

“Clearly, people understood how to mark the ballot effectively,” said Chris Hughes, policy director of the Ranked Choice Voting Resource Center, a national nonprofit devoted to informing the public about ranked choice voting.

“The overall (overvote) rate was honestly one of the lowest I’ve ever seen,” Hughes said.

That’s an indication that education campaigns by the division and by Alaskans for Better Elections — a nonprofit that encourages ranked choice voting — were successful.

A poll commissioned by the nonprofit found that 95% of voters reported receiving instructions on how to use ranked choice voting, and 85% of voters said it was simple.

We won’t know until next week how many of Palin’s voters and Peltola’s voters picked a second candidate, but more than 80% of Republican candidate Nick Begich’s supporters picked at least one additional candidate.

“Which is pretty solid, especially for the first time using ranked choice voting,” Hughes said.

About 6% of voters ranked only one or two candidates and had all of their options eliminated, creating what are known as “exhausted” ballots.

In some cases, that was because the voter didn’t like the remaining options. In others, it may have been because of confusion or out of protest, but it’s impossible to judge how many people fell into each category.

Palin, supported by former President Donald Trump, urged her supporters to rank only one candidate.

Tom Anderson of Optima Public Relations ran some of Palin’s advertising campaign and is working with some conservative legislative candidates.

“From the circles that I work within, they did not like the system, even if they were benefactors of it,” he said.

Ivan Moore of Alaska Survey Research, said his numbers indicate conservative Alaskans dislike ranked choice voting by a 6-1 margin, while moderates and progressives support it.

The election didn’t run perfectly. As many as seven rural communities may have had their ranked choice ballots excluded from the final result because they failed to arrive in Juneau by mail. Elections officials have said they will use express mail for the November general election.

And two rural polling places didn’t open at all on election day. In those cases, poll workers didn’t show up, and no one told election administrators until the day after.

Begich voters decided the result

Immediately after learning of her defeat, Palin blamed ranked choice voting, and some other Republicans followed suit.

Observers say her failure to sway Begich supporters was to blame.

“Mary didn’t win because of ranked choice voting. Mary won in the final equation because she was running against Sarah Palin and people didn’t like Sarah Palin,” Moore said.

Matt Larkin runs Dittman Research, which runs polls for Republicans in Alaska and said Palin is disapproved of by many voters, which explains why about half of Begich supporters voted for Peltola or no one at all after he was eliminated.

“I definitely think more Republicans chose not to rank than was expected,” said Sara Erkmann-Ward, a Republican consultant who tried to convince conservatives to rank multiple candidates.

Had more Begich supporters turned their second-choice votes in favor of Palin, she would be on her way to Washington, D.C., instead of Peltola.

Political parties had less influence

Begich was the preferred candidate of the Alaska Republican Party, which endorsed him while largely shunning Palin. Despite that support, he finished third among the three candidates and was the first eliminated.

The party also ran a “rank the red” campaign to encourage Begich and Palin supporters to rank the other as their second choice, but too few Republicans followed party instructions to give Palin the win after Begich was eliminated.

It’s premature to say the “rank the red” campaign failed, Larkin said, but “it’s probably clear that it could have worked better than it did.”

Erkmann-Ward, who worked on the campaign, said the outcome is “a natural outcrop” of the fact that political parties have been “kind of sidelined” throughout the election, not just in ranked choice voting.

The state’s new electoral system allows up to four candidates, regardless of party, to advance through the primary election.

In a special election like this one, that was particularly important because the state’s former laws allowed a political party to pick its special-election candidate without a primary election.

In this case, the Republicans may have picked Begich, and the Democratic establishment may have picked someone like Christopher Constant, who had significant early support from Anchorage party officials but faded as Peltola gained popularity in the primary campaign.

In future elections, the top-four primary means Republicans or Democrats may advance to November without party support, giving independent voters options that party leaders may disapprove of. In this election, that was Palin.

Niceness matters

In the runup to the election, Palin and Begich traded barbed comments in an attempt to sway Republican voters toward their side. Observers say that may have been counterproductive, with Palin’s comments alienating the Begich supporters she needed to win.

“I think that maybe one of the lessons learned on the Republican side coming out of this is that ranked choice really cannot work the way you want if two members of the same party are really heavily attacking one another,” Larkin said.

Peltola was on the sidelines of that intra-party conflict and maintained good relations with Palin throughout the campaign.

Peltola, a former state legislator, had a reputation for courtesy even before this year’s campaign, and one Alaska Public Media article described her attitude and reputation as a “superpower.”

Anderson said he believes that made a difference.

“She was untouchable because of her courtesy. I think people didn’t even want to go there,” he said.

He doesn’t expect that approach to last. Because Peltola won in August, she will be a target for both Palin and Begich in November, he said.

“I think the gloves are going to come off,” Anderson said, and added that he doesn’t think Palin and Begich will “make up” before the next election.

November will be different

Even if the candidates’ campaign styles may not change before November, pollers, observers and advisers say August’s results shouldn’t be directly applied to November.

Turnout is expected to be much higher in November than August, and moderate voters are more likely to participate.

Larkin used a football analogy, saying that any changes campaigns make now are akin to “halftime adjustments,” now that all sides have seen each other in action.

In addition, the November U.S. House election will include a fourth candidate, Libertarian Chris Bye, who could add a new wrinkle even though he received less than 1% of the primary-election vote.

It’s also a mistake, Larkin said, to think that August’s U.S. House results mean much for the statewide U.S. Senate or governor races.

“The composition of each field will create its own ‘weather,’” Larkin said.

And even with all the things we now know about ranked choice voting, the sheer uncertainty of a political campaign means almost anything can happen in the next two months.

“It’s Alaska politics. Heck, we could have an asteroid hit between now and then,” Erkmann-Ward said.

James Brooks is a longtime Alaska reporter, having previously worked at the Anchorage Daily News, Juneau Empire, Kodiak Mirror and Fairbanks Daily News-Miner.

This article originally appeared online at alaskabeacon.com. Alaska Beacon, an affiliate of States Newsroom, is an independent, nonpartisan news organization focused on connecting Alaskans to their state government.