When a Kenai Peninsula artist finishes a piece, the work may hang for a few months on the walls of a local shop or gallery. If sold, it will vanish into a private home or office. If not, it returns to the artist’s studio. Either way, an artwork’s public life is limited.

Soldotna’s Joyce K. Carver Memorial Library and Soldotna-based arts nonprofit ARTSpace hope to extend that life indefinitely by putting a collection of photobooks, reproducing the works of local artists, on the library shelves. ARTSpace director Joe Kashi said the project will preserve work for the community.

“Otherwise it’s lost,” said Kashi, who studied high-energy physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “Having been trained in the sciences, I’m a strong believer in never throwing away data or losing data.”

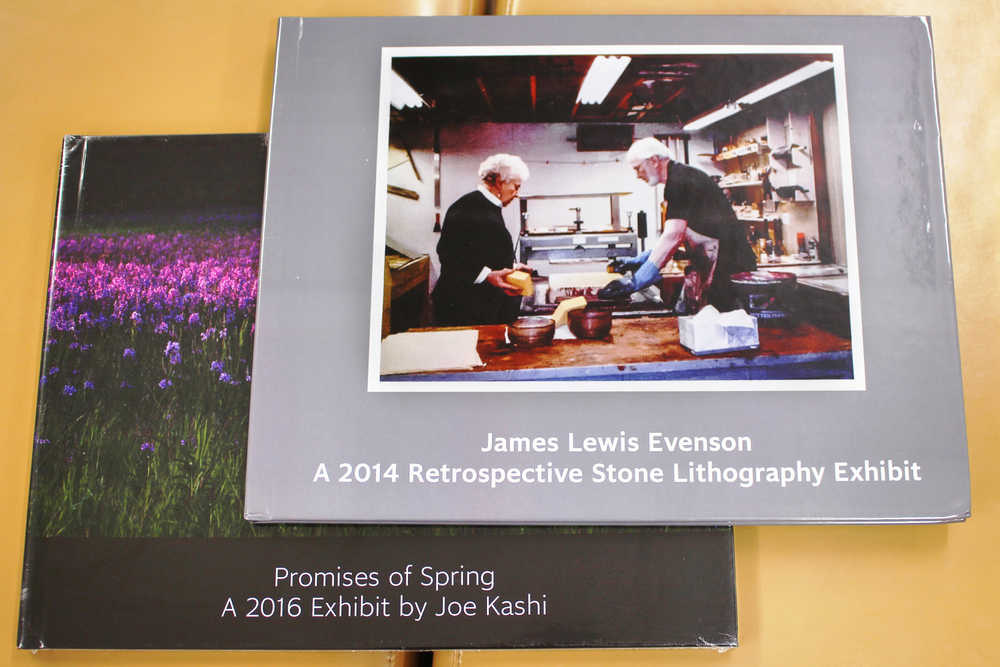

The collection presently consists of five books, which have yet to be cataloged and shelved: two copies of a lithograph collection by homesteader, commercial fisherman, and lithographer Jim Evenson (which ARTSpace produced and donated to the library in early September), along with three books of Kashi’s photography, two of which collect photos he exhibited at Kenai Peninsula College in 2014 and at Alaska Pacific University in 2015.

Kashi said the archive will be “lightly curated.”

“Our approach is to be as low-cost as possible and as inclusive as possible, in terms of not having a clique but bringing in everybody, including people who are outside of the usual groups,” Kashi said. “We’re trying to be as democratic as we can, but at the same time we want to keep a reasonable minimal level of quality.”

Once established, Kashi hopes the collection will expand with contributions volunteered by local artists. To encourage this expansion, he’s leading a free class this Saturday from 1 p.m to 3 p.m at the Soldotna library, where interested artists can learn how to use ARTSpace’s camera, lights, and software to create coffee-table size photo book reproducing their work.

“One of the real problems for people — especially for younger artists, who we tend to focus upon — has been the cost of having their artwork professionally copied,” Kashi said. “Doing good photography on artwork requires care and finesse. It requires decent equipment, ideally experience. But not everybody can afford that… Part one of our training will be showing the people how to go and actually use the minimalist art copy equipment over at the Soldotna library, which includes a new Pentax camera with a good sharp lens, it includes copy lights, and then Adobe Lightroom on the computer, so they can go and make the best quality images for the book.”

Last year, ARTSpace donated the camera, lights, and image-processing computer to the library, where they are free to use for artists who have taken training classes such as the one offered on Saturday. Once they’ve managed to get clean, undistorted images of their work, the artists can send images to companies such as the New York-based print on demand service My Publisher, which Kashi said he favors for their relatively inexpensive large-scale photobooks. According to its website, My Publisher offers a 20-page 15 inch by 11.5 inch book for $64.99.

In a cultural world where many young artists find their first audience online and build reputations by displaying work on the internet, Kashi said keeping local artwork in physical books has both aesthetic advantages for the present and archival advantages for the future.

“A properly-made book or a properly-created print has a better range of tone and depth than the 8-bit color that’s available on the standard computer monitor,” Kashi said. “It has a much better presence because it tends to be larger, and with a book you can linger, whereas with images on a screen people tend to look through within a few seconds — boom, boom, boom — which makes no sense.”

On the technical side, Kashi recited a growing list of problems that scientific, legal, and artistic archivists have with the rapid creation and obsolescence of digital storage formats.

“Standards change regularly, software become unavailable to read older file formats,” Kashi said. “There’s no clear, easy, single way to update older formats to more modern formats — especially given the multiplicity of formats that exist. You also have to have the hardware that can run that particular program, if it exists… In contrast, you pick up a piece a paper and as long as you have eyes and vision, you can physically mount the data, if you will. Pick up the book, and if you open your eyes you can see it and if you’re literate you can read it. You have all the hardware and software that’s needed.”

Reach Ben Boettger at ben.boettger@peninsulaclarion.com