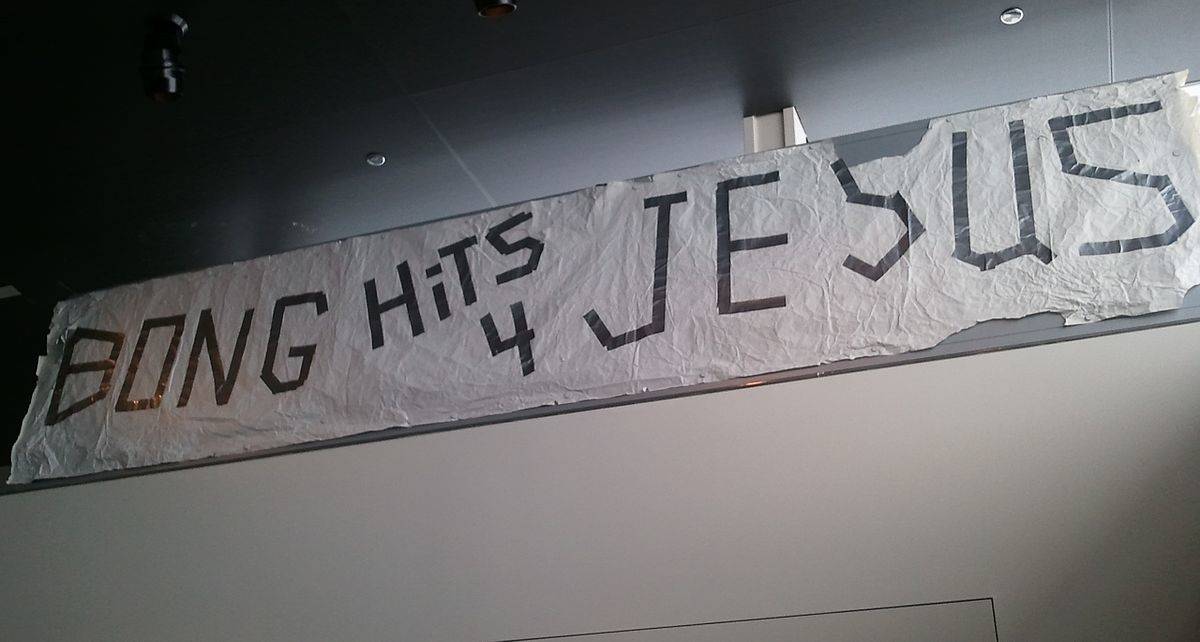

The banner reading “Bong Hits 4 Jesus” at the center of a U.S. Supreme Court decision has been sent to a museum in Maine after failing to find a home in Juneau where it was first made.

The banner had been on display at the Newseum in Washington, D.C., but that museum recently closed, according to Doug Mertz, a lawyer for the banner’s owner. The Juneau-Douglas City Museum was unable to display the banner because of its size, Mertz said.

The banner’s owner, Joseph Frederick, wants to hold on to it in the hopes of somehow monetizing it to create a college fund for his two young daughters, Mertz said. Frederick currently lives in Wuhan, China, Mertz said, and tried to find a home for the banner in Juneau. The Alaska State Library and Museum has other artifacts from the case, Mertz said, but would only accept the banner as a donation.

The banner, made of duct tape and butcher paper, was mailed Tuesday to the First Amendment Museum in Augusta, Maine. The museum is planning to have the banner professionally treated in order to preserve it, Mertz said, but since Frederick still retained ownership of the banner, there’s a chance it could return to Juneau. The museum currently has the banner on a five-year loan, Mertz said.

The banner arrived at the First Amendment Museum Thursday, according to Max Nosbisch, manager of visitor experiences, and will be sent to a professional in Indianapolis for preservation treatment before being returned to the museum for display.

“One of our challenges is just finding a wall big enough,” Nosbisch said of the banner, which is about 16 feet long.

The case began in 2002, when Juneau-Douglas High School student Joseph Frederick held the banner up across the street from the school as the Olympic Torch Relay was running by. The school’s then-principal, Deborah Morse, took the banner and suspended Frederick for 10 days. Frederick sued, arguing his First Amendment rights had been violated.

[New bill would allow Alaskans to know when data is collected]

A student’s free speech is protected so long as it doesn’t significantly disrupt the learning process, Mertz said, but for Frederick’s case the Supreme Court created an exemption. Because the banner made a specific reference to drug use, the court ruled that there was an exception for a student’s free speech when authorities can reasonably conclude the speech is promoting illegal drug use, according to the Federal Court’s summation of the case. Marijuana wasn’t legalized in Alaska until 2014.

“The Court held that schools may ‘take steps to safeguard those entrusted to their care from speech that can reasonably be regarded as encouraging illegal drug use’ without violating a student’s First Amendment rights,” the summation says.

Frederick and the Juneau School District eventually settled, Mertz said, but the case set an important precedent for future cases.

It’s an issue that still resonates Mertz said. Later this month the U.S. Supreme Court is set to hear another case regarding student free speech. That case involves a Pennsylvania high school student who posted a profanity-laden rant against her school on social media after being rejected from the varsity cheerleading squad.

Mertz said with new technologies and more ways for students to express themselves the question of how far a school’s jurisdiction is being tested.

“I’m interested to hear the oral arguments,” Mertz said. “What if a student provides false and slanderous information about somebody at the school? Can the school do something about that?”