Two research efforts are taking new approaches to the question of why Cook Inlet’s endangered beluga whales haven’t recovered since hunting restrictions were placed on them in 1999.

Projects by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game and other collaborators aim to close gaps in a basic understanding of Cook Inlet beluga life by examining the large volumes of data collected over past decades of research.

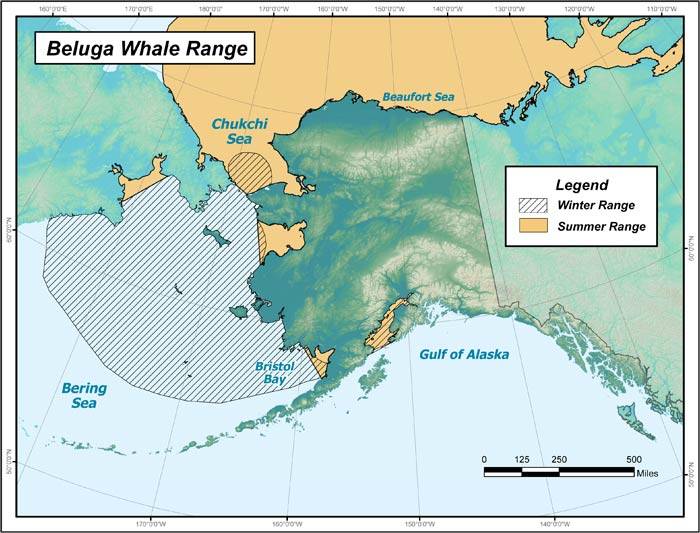

Cook Inlet belugas — one of Alaska’s five distinct beluga populations — were estimated to number 1,293 in a 1979 survey. Because of unregulated subsistence hunting, this number dropped by 47 percent between 1994 and 1998, according to the whale’s federal managing agency, the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration’s National Marine Fisheries Service. This trend led NMFS and Alaska Native groups to establish the 1999 harvest limitations. The last authorized beluga hunt in 2005 took two whales.

“This reduction in hunting should have allowed the (Cook Inlet) beluga population to begin increasing at an expected growth rate of between 2 percent and 6 percent per year if subsistence harvest was the only factor limiting population growth,” NMFSs beluga whale recovery plan states. “However, abundance data collected since 1999 indicated that the population did not increase as expected.”

Further conservation measures followed: in October 2008, NMFS designated the Cook Inlet belugas as endangered under the Endangered Species Act, and in April 2011 the agency protected 3,016 square miles of Cook Inlet as critical habitat for belugas. Yet the beluga population has continued an annual decline of about 1.3 percent since 1999, leading to the present NMFS-estimated population of 340 whales.

Alaska Department of Fish and Game wildlife biologist Lori Quakenbush said that when she began studying belugas in 2002, researchers were noticing more beluga calves in the groups they observed, leading them to believe that with harvest restricted, the population would begin rebounding in about six years or so.

“Now that the harvest has stopped and the population hasn’t increased, we’re thinking that simultaneously something else was going on,” Quakenbush said. “We thought it was a pretty simple case of more animals being removed from the population than are being born into it, and that’s not a difficult equation. But if you’ve got something else going on at the same time — maybe something with their food availability or potentially something with their social structure — the potential’s there for those kinds of things and we just don’t know until we start putting it together…

We’ve looked at contaminants, disease, reproduction — but nothing has come out to be a good answer. We had ten years of data being collected, and now we have some datasets we can put together and really try to figure out what’s going on.”

Puzzle pieces

Putting it together will be the work of several groups collaborating on a pair of three-year projects under Fish and Game’s leadership. One will look for changes over the past 50 years in where belugas gather and what they eat. Another will estimate beluga birth and death rates with a novel model based on data that could range from genetics to satellite tracking.

The two projects, scheduled to start this fall, will be together getting $1.26 million in federal money over the next three years. The Georgia and John G. Shedd aquariums are matching the funds.

Quakenbush’s part of the project is using genetic data to draw inferences about how Cook Inlet belugas relate to one another.

In contrast to Cook Inlet’s dwindling stock, the healthy and stable beluga population of Bristol Bay numbers around 2,000. These whales have been studied through remote biopsy — collecting tissue with a hollow tethered dart. Quakenbush said researchers have picked up about 700 biopsies, alongside observations of which animals were spotted near one another. The biopsies are presently being analyzed by a lab in Florida, she said, to produce genetic data that will show which whales are related to one another. Combining that data with observations of how the whales interact — whether mothers and children swim alongside one another, for instance — will let researchers “understand more about beluga social structure and kinship — how they’re related to one another and how they operate, and how that might influence their mating system,” Quakenbush said.

For the Cook Inlet belugas, there’s no set of genetic data similar to the biopsies from Bristol Bay. NMFS’ five-year recovery plan for Cook Inlet belugas estimates such a program would cost about $300,000 annually. Correlating behaviors with kinship will have to be done instead by inference.

One tool for doing so could be the large set of photographs collected in the Cook Inlet Beluga Whale Photo-ID database, a project of biologist Tamara McGuire, whose group LGL Research has tracked sightings of about 376 individual belugas since beginning in 2005.

The database consists of photos of arched whale backs curving out of Cook Inlet’s opaque water, identifiable by old scars and other markings. Though McGuire said she’s found no reliable way of telling the sex of a beluga from their visible backs, tracking a whale’s consistent proximity to other whales “will tell you who they’re associating with, and we’ll try to guess at the relationship — if we see a bigger whale and a smaller calf next to it, and we consistently see them over time, we assume they’re mom and calf, but we don’t know that.” The kinship data from Bristol Bay could make those assumptions firmer.

Quakenbush said a better understanding of beluga kinship — a mostly unknown aspect not only in Cook Inlet but worldwide, she said — could help answer the riddle of population decline by showing “whether certain individuals do most of the breeding or not.”

“That could be a large factor in how the population operates,” Quakenbush said.

“We know belugas are social, we know they feed cooperatively. And if you have a population where all the adults are capable of breeding, and they do so as often as they can, that population has the potential to grow pretty fast. But if you have a population that’s very social, and somehow their socialness limits most of the adults from breeding — like a wolf pack, where you’ve got alphas and betas, and the alphas breed in most years and the betas do not — that population’s going to grow at a very different rate if there’s mature adults who aren’t breeding for social reasons.”

McGuire said the results of the present research will allow future research to be more specific. Previous studies, she said, have been less focused because researchers didn’t know whether to concentrate on beluga reproduction or mortality. Soon there may be more clues to where the problems lie.

Quakenbush said a strength of the new research is that it’s “really a team of people with different expertise who are going to come together to look at the data.”

“With these types of projects we’re not really looking at one thing — we’re looking at multiple things together, and I think that’s what we need to be doing to figure it out,” she said. “If it were a simple answer, we probably would know what it is by now.”

Sex and death in Cook Inlet

The population surveys used to establish the Cook Inlet belugas as an endangered species and to justify the hunting moratorium were based on aerial surveys that recorded trends in overall population. To examine why this population hasn’t yet responded to conservation measures, researchers are using a new tactic: estimating rates of beluga reproduction and death based on factors affecting them at an individual level.

Charlotte Boyd of NMFS’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center will construct the model. She wrote in an email that population models using individual factors are becoming more widespread due to the increasing power of computers and should fit well with the small population of Cook Inlet belugas.

“Individual-based methods are well-suited to analyzing the current status and future prospects of small populations that may have imbalanced age- or sex-structure (e.g. few reproductive-aged animals but many young or senescent animals) as often occurs with populations that have been selectively hunted,” Boyd wrote. “Over time, the population will be expected to return to a stable age- and sex-structure, but this can take time. Recruitment and survival rates are expected to change over this time period rather than remain constant as is generally assumed in population-level models.”

Quakenbush’s kinship analysis and McGuire’s photo-ID datasets could be two sources of individual-level information contributing to this model. Others may be migration patterns observed by satellite-tracking and necropsies of stranded belugas on Cook Inlet’s beaches. Boyd wrote that the Fish and Game research will help NMFS decide what data is needed for the model.

McGuire described the individual factors as a “fine-tuning” of past population-level studies. The shrinking beluga population must be due to either a low birth rate or a high death rate, “or some combination of the two,” McGuire said. “You don’t know which, you just know the ratio is off.”

“Once you start to get into individual-based modeling — especially let’s say we have information now about moms and calves — you can start looking at birth rate,” McGuire wrote. “We can say, what can we learn from individuals about birth rate? Are they having calves as often as they should if they were a healthy population? Are their calves living the first year at rates you’d expect if they were healthy? Is the birthrate healthy or not? We’re just beginning to study that, so we don’t know.”

As for how belugas die, Boyd wrote that “some information on causes of mortality can be gleaned from necropsies of stranded animals, but sample sizes are small and dead-stranded animals may not be representative of the causes of death of all animals that die in a given year.”

“In particular, very few stranded animals are recovered in the winter months, yet we think this is the season when Cook Inlet belugas are most likely food-limited,” she wrote.

Teeth

“A primary uncertainty in trying to understand the failure of the Cook Inlet beluga whale population to recover is whether the quantity or quality of available prey is limiting recovery through constraints to Cook Inlet beluga whale reproduction or survival,” the NMFS recovery plan states. “Because not all prey species contribute equally to Cook Inlet belugas’ diet, and the nutritional characteristics of a given prey species vary seasonally, research is needed to understand the quantity, quality, and distribution of prey available in Cook Inlet beluga habitat, and how these characteristics vary spatially and seasonally.”

Fish and Game wildlife physiologist Mandy Keogh is examining this question as primary investigator of the second three-year study, funded with $850,641 from NMFS. She’ll be working with another large, long-term trove of biological data: teeth from stranded belugas, covering about 50 years in beluga lifespans. Chemicals in the teeth correspond to different locations and different prey, showing what the whales were eating and where at different points in their lives.

“Beluga whales have a layer of tooth that’s laid down each year,” Keogh said. “We’re able to track that almost like what you’d see in a tree. So we’re able to determine where they’re foraging and generally what their diet is. That will give us a historical perspective of where they’ve been foraging for the past fifty years, and whether or not that has shifted recently, and when that shift actually occurred.”

Looking across individuals over a 50 year span, she’ll be able to piece together a wide picture of change.

“Are they eating more freshwater fish than they used to, or are they eating a different type of fish?” Keogh said. “That will give us some information and we can start to explore why that may be — maybe preferences have changed or the prey availability has changed. How they’ve changed over the last 50 years, before and after the decline, might give us an indication of what’s preventing them from recovering.”

Another project Keogh is leading will station underwater microphones in the Inlet to “see acoustically where belugas are foraging,” she said.

“It’ll also record all the ambient noise, so we’ll be able to record any natural or anthropogenic noise that’s in their environment,” Keogh said.

The winter foraging habits of belugas are among the basic facts about the population that have remained unknown — in part, Keogh said, because “Cook Inlet is rough on equipment” with shifting ice, powerful tides, and silty water, and in part because the lack of fishing in winter has eliminated a possible source of data on seasonal prey abundance. Keogh said now is an opportune time to look harder at such basic questions.

“We have the datasets and the samples available so we can start asking these questions,” she said. “10 years ago, we didn’t have either the methods or the tools to be able to test these and understand what’s going on.”