The Kenai Peninsula Borough Assembly took a first step Tuesday toward securing emergency services in an area that has few residents, but sees thousands of people each day — 113 miles of highway running through the mountainous and sparsely populated eastern peninsula.

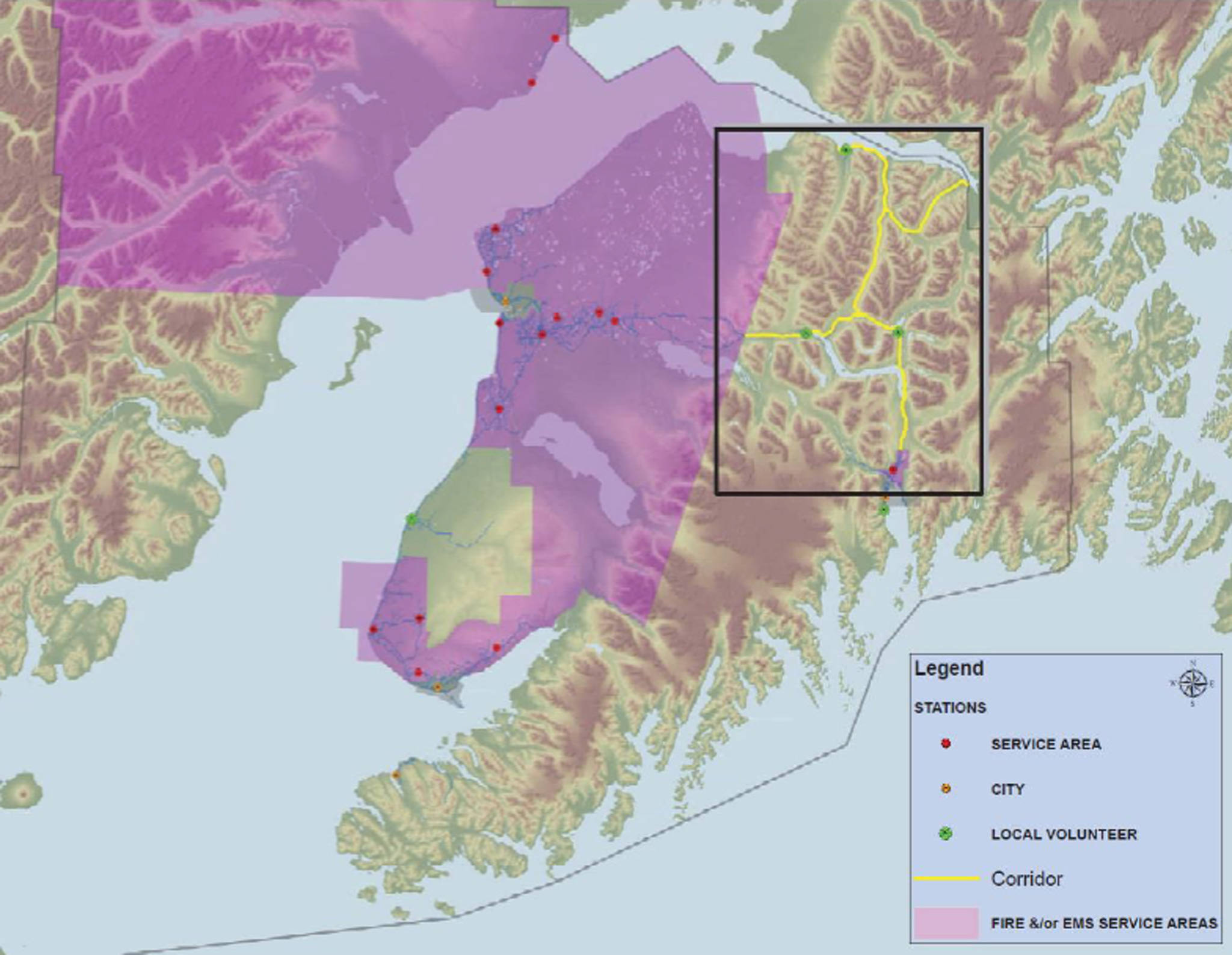

The assembly unanimously voted Tuesday to have Borough Mayor Mike Navarre’s office begin studying the feasibility of creating an emergency service area(map) consisting only of the corridors of the Hope Highway, the Seward Highway south of Turnagain Arm and the Sterling Highway east of mile 58, with the intent to provide better emergency response on these roads.

The ordinance cites Alaska Department of Transportation statistics which show that in 2015 these roads had an average daily traffic of 3,000-4,000 vehicles, with a summer peak three times higher. In 2015 and 2016, about 180 people were injured in 126 car accidents on these highways, according to the ordinance text.

For many of these accidents, the first rescuers on scene came from small volunteer emergency groups in Cooper Landing, Moose Pass and Hope. The eastern highways are not within any of the five emergency service areas that cover most of the more heavily-populated western peninsula, though they often receive mutual aid from Seward’s Bear Creek Fire and Emergency Service or the west peninsula’s Central Emergency Services(map), whose closest station is in Sterling. Ninilchik resident Lara McGinnis, testifying in support of a service area in the highway corridor, described to assembly members a head-on collision she had in this area in March 2016.

“I held my own compound fracture for over ninety minutes,” McGinnis said. “We couldn’t bring in a helicopter. Cooper Landing was there within fifteen minutes. Moose Pass was there. They were able to cut the top off my car but they could not get me out. I lost three units of blood until CES could finally get there. … Ninety minutes is an unacceptable period of time.”

Cooper Landing, which as a census-designated place has no legal authority to tax its residents, pays for its volunteer emergency responders with donations. Much of their activity, though, is outside Cooper Landing. Roughly half of the 254 calls for emergency transport that Cooper Landing Emergency Services responded to between 2013 and 2015 came from outside the town, according to previous Clarion reporting.

Cooper Landing Emergency Services President Dan Michels wrote to the assembly that his organization has no local emergency medical technicians. Instead, they are paying a single weekday EMT who lives in housing donated by a local business, and on weekends are covered by volunteers who come from elsewhere on the peninsula. Cooper Landing Emergency Services is also expecting a $40,000 deficit this year, he wrote.

“We cannot sustain this for very long,” Michels wrote. “Somehow the system needs to change.”

Solutions

The borough, CES and Cooper Landing Emergency Services have been talking about issues with peninsula emergency services since last spring when they were called together for a meeting to remind the agencies about the terms of their mutual aid agreement. Mutual aid can technically only be called for when an emergency service agency has already responded to an accident and then decides additional help is needed, but some calls had been being routed directly to CES when Cooper Landing volunteers were not available.

Problems with emergency services were also raised by a borough health care taskforce commissioned by Navarre, which named emergency medical services as one area in which “substantial gaps exist borough-wide” in an Oct. 2016 presentation to the assembly. An emergency medical services workgroup was spun off of the healthcare task force to continue work on the problem. On Tuesday that group’s co-chair Stormy Brown presented assembly members with three solutions it had examined, one of which the assembly voted to pursue.

One way to bring increased emergency service to the area would be for the borough to dissolve its five existing emergency service areas and create a single service area covering the entire borough.

Brown said that though the borough’s existing emergency service areas — created by vote of their residents and funded by taxation of those residents — probably aren’t optimally arranged, their history makes them hard to restructure.

“Unweaving what has been woven into service areas that have spent their citizens’ time and money building up their funds and resources … we found it very challenging to take the concept to them,” Brown said. “In order to do borough-wide powers for (emergency medical services), the service areas couldn’t have those powers anymore. They would have to give up those powers, and the funding that goes with it from each of their budgets, so that we could combine it, tax the rest of the borough, and redistribute it. We found that to be probably challenging at the ballot.”

Another option would be encouraging communities along the corridor to create a traditional service area. Taking this option would require “asking the few tax-eligible residents in the area to tax themselves to provide a service utilized largely by non-local users,” according to Brown’s presentation to the assembly. Even if that were to occur, the borough still might not be able to raise necessary funds.

“The tax base isn’t there because of the federal lands,” Brown said.

Outside these small communities, almost all the land surrounding the highway is owned by the U.S Forest Service as part of the Chugach National Forest. This land is closed to development and has no property tax value. The borough is compensated for this untaxable land by payments from the federal government — known as payments in lieu of taxes, or PILT. In its current fiscal year 2017 budget, the borough records $3.32 million in federal revenue, and Navarre wrote in a memo to the assembly that he anticipates $2.6 million in PILT in the coming fiscal year, which will go into the borough’s general fund.

The solution the borough assembly began chasing on Tuesday is to create a new service area that would cover only the road corridor and exclude the communities and scattered residents alongside it, who would continue to get emergency services from local volunteer organizations. This service area would be paid for with the federal PILT money.

Assembly members voted unanimously to begin analyzing this solution. Brown said the cost of the proposed service area would be estimated as part of this analysis.

Legal work required

The highway corridor is a odd puzzle piece that doesn’t fit clearly into existing law about how service areas can form. Previously, borough code only allowed a service area to be established by a petition of area residents. Tuesday’s ordinance made the petition requirement conditional on residents living in an area and created an alternative way to establish service areas: the assembly can now pass a resolution recommending that the mayor’s office first study a potential service area, then present an ordinance to create it.

The assembly both created this process and passed an initiating resolution on Tuesday. The next steps will require Navarre’s office to research and analyze the service area’s cost, design and timeline with public feedback, then propose an ordinance to create the service area for the assembly’s vote.

Though state law allows a borough to create service areas by ordinance in places without registered voters, it requires written permission of all real property owners in the area. In the case of the road corridor service area, this would be difficult, according to Brown.

“The nuances and legal complexities of right-of-way and easement ownership make sorting out the definition of ‘real property owner’ on the highway challenging, although not impossible,” the text of her presentation states.

A simpler option is getting a statute change through the Alaska Legislature. A bill introduced March 1 by Reps. Mike Chenault (R-Nikiski) and Gary Knopp (R-Kenai) would allow the creation of service areas in state highway corridors where no voters live. This would “significantly streamline the process and reduce complexity,” the presentation states. A Senate version was introduced by Sen. Peter Micciche (R-Soldotna) on March 3. Both are presently referred to the Community and Regional Affairs committees of their respective bodies.

Though the assembly unanimously authorized the mayor’s staff to start planning and analyzing the service area proposal, some assembly members expressed longer-term concerns about it. Assembly member Wayne Ogle said he is dubious of the funding mechanism.

“PILT — I think that’s the way to go, but I worry about the feds coming through with their dollars in a timely fashion,” Ogle said. “I think in the past there’s been some welching of the PILT money. But I look to seeing what’s coming, and I’m glad we’re moving forward on it.”

Ben Boettger can be reached at ben.boettger@peninsulaclarion.com.