Although the invasive water-weed elodea was officially eradicated from the Kenai Peninsula this summer, the statewide threat remains.

Floatplanes, which can inadvertently carry colonies of the plant to remote locations in their floats and rudders, are significant vectors of the weed, and the possibility of undetected elodea populations in inaccessible lakes has complicated efforts to eliminate the invader. University of Alaska researcher Tobias Schwörer — an economist at the university’s Institute of Social and Economic Research — is attempting to shed a statistical light on these hard-to-detect elodea populations with a model that estimates a given lake’s probability of harboring elodea based on how often lakes are visited by floatplanes.

Growing in dense stalks up to 8 feet, elodea can fill up a water body’s volume, increase its sedimentation and deplete its oxygen. When state wildlife managers began to take note of elodea’s ecological damage — around 2009, when the plant was found in Chena Slough near Fairbanks — Schwörer said “there was always talk about how this affects first the ecosystem, and second, other things.”

“People were saying ‘Maybe salmon are going to be affected by this, and what about commercial fisheries,’ and such and such,” Schwörer said. “And myself, as an economist, said ‘I need to look at this more closely in order to put some potential damage numbers to this invasive.’”

To that end, Schwörer is writing a dissertation on the ecological invader’s economic impact.

“The question is, to what degree does elodea make sense to manage, and if so, what are the justifications?” Schwörer said. “As you know, it’s very expensive to eradicate this.”

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Chief Biologist John Morton — who led an aggressive effort to eliminate elodea in three Peninsula Lakes — estimated the local anti-elodea fight had cost about $500,000 in funding from the Kenai Peninsula Borough and the Fish and Wildlife Service, the refuge’s federal parent agency. This effort involved monitoring for elodea at 150 sampling points in the three lakes for two years and using two different herbicides to kill it. After starting the herbicide application in 2014, Morton announced the three lakes were elodea-free in 2016.

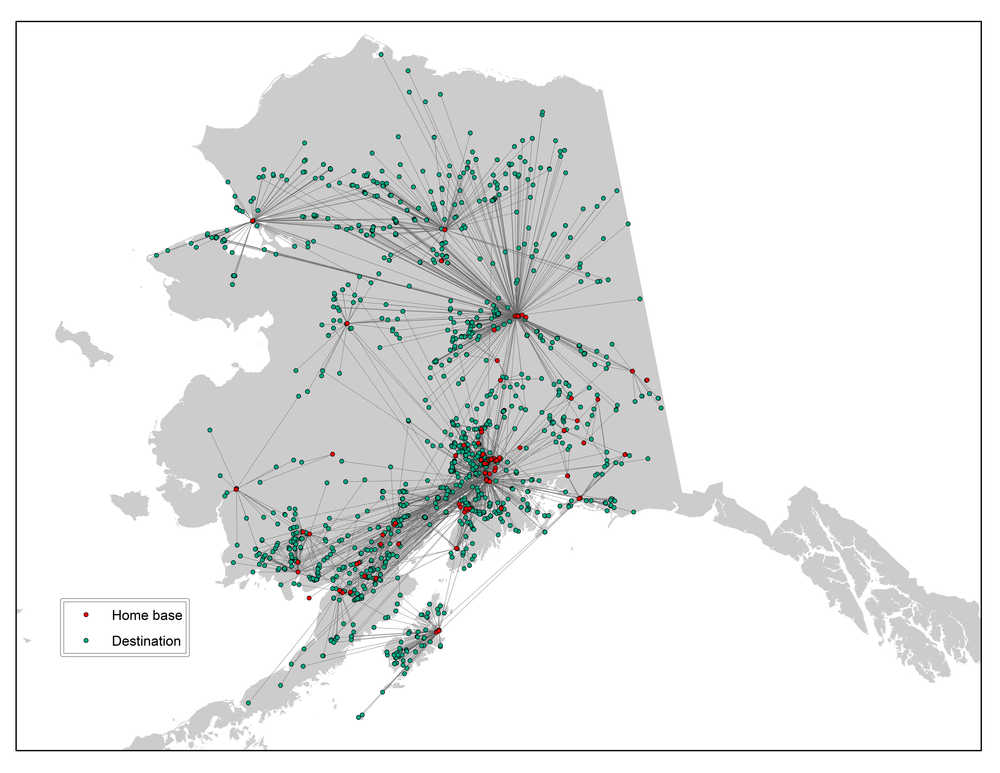

In tackling the question of elodea’s cost, Schwörer is investigating the economic sectors it may touch, starting with floatplane activity. In addition to the economic analysis, his floatplane route mapping will have practical value to state wildlife managers attempting to control elodea. In early control efforts, Schwörer said a big problem was figuring out where the threat is. According to the Alaska Conservation Foundation, the state has 3 million lakes. Schwörer said finding and targeting elodea populations in those lakes was “like finding a needle in a haystack.”

Although elodea was introduced as a dumped aquarium ornament, floatplanes have since accounted for most of its spread, Schwörer said. When elodea was discovered in Anchorage’s Lake Hood — the busiest floatplane base in the world — in June 2015, managers feared that elodea would spread faster.

Schwörer contacted both private recreational floatplane pilots and commercial floatplane operators in a survey he said had a response rate between 50 percent and 70 percent. Using phone calls, mailed forms, and an online voluntary flight-mapping tool, Schwörer said he “got a good sense of where they fly, and how many flights they took last year into each location.”

To get an equally good sense of what value might be lost to elodea, Schwörer used the same survey to estimate each lake’s intangible benefit to pilots.

“We also asked ‘given this location, Lake A, that you fly into 100 times each year — what if that lake gets infested with elodea?’” Schwörer asked. “Most people were familiar with what that looks like from Lake Hood, so most pilots can relate to that hazard… We asked ‘would you still fly there? And if you did, would you fly less?’ You can imagine that for a commercial operator who’s flying to Chelatna Lake to take clients fishing, if they couldn’t fly there anymore, that would have an impact to the industry.”

When the analysis is complete, each lake will have a score measuring how likely it is to be infected with elodea. Shwörer’s model will be able to make this probability prediction for lakes that are difficult to survey directly.

Based on survey responses and on a lake’s fetch — a measurement of how wind blows on a lake’s surface, an important factor in whether a floatplane can land — Shwörer said he can come up with “basically a likelihood model that tells me ‘Lake Z is not showing up in my sample, but I can tell based on its location and based on its fetch, that it is most likely to also be part of the locations people fly to … You can then say to managing agencies: If you want to plan your monitoring or surveillance or whatever looking around for this stuff, go for those lakes with the high probabilities … You can have a targeted approach, and you don’t have to go after a needle in a haystack. You can go after this in a strategic way.”

Aiding elodea managers is his ultimate goal, Schwörer said.

“I’m trying to help with applying social science methods to justify actions, or first to analyze management options, then to justify certain management options,” he said. “That means quantifying the potential damages if nothing is being done.”

Some work still remains in that quantifying effort. Another aspect of Schwörer’s economic research on elodea examines the fishing industry, where ecological data on how salmon are affected by the weed is scanty, he said, due to the time and money such research would require. Fish biologists he’s consulted have given him opinions, however, which he says result in a mixed picture of how salmon could suffer or benefit from elodea in their habitats.

“There’s no scientific evidence to this day that (elodea) harms salmon,” Schwörer said. “So the question becomes: if people are of the opinion that this harms salmon, how we quantify that expert opinion? … The results mainly show that experts are very concerned, and there could be negative effects, but there could also be positive effects.”

Ultimately, the question of how much the state-wide eradication effort is worth will be balanced against its cost. Although his analysis is incomplete, Schwörer said he believes totally eradicating elodea, if possible, would have “a very high price tag.”

“Imagine if this would take $1 billion in management costs,” Schwörer said. “I just threw that number out, but imagine if that would be the case. People would argue, ‘imagine if you use that billion to fund education, or put it in the savings account as an endowment.’ These are all society’s trade-offs. It will be a political decision in the end, anyway.”

Reach Ben Boettger at ben.boettger@peninsulaclarion.com.