By Mark Thiessen

Associated Press

ANCHORAGE — Seal oil has been a staple in the diet of Alaska’s Inupiat for generations.

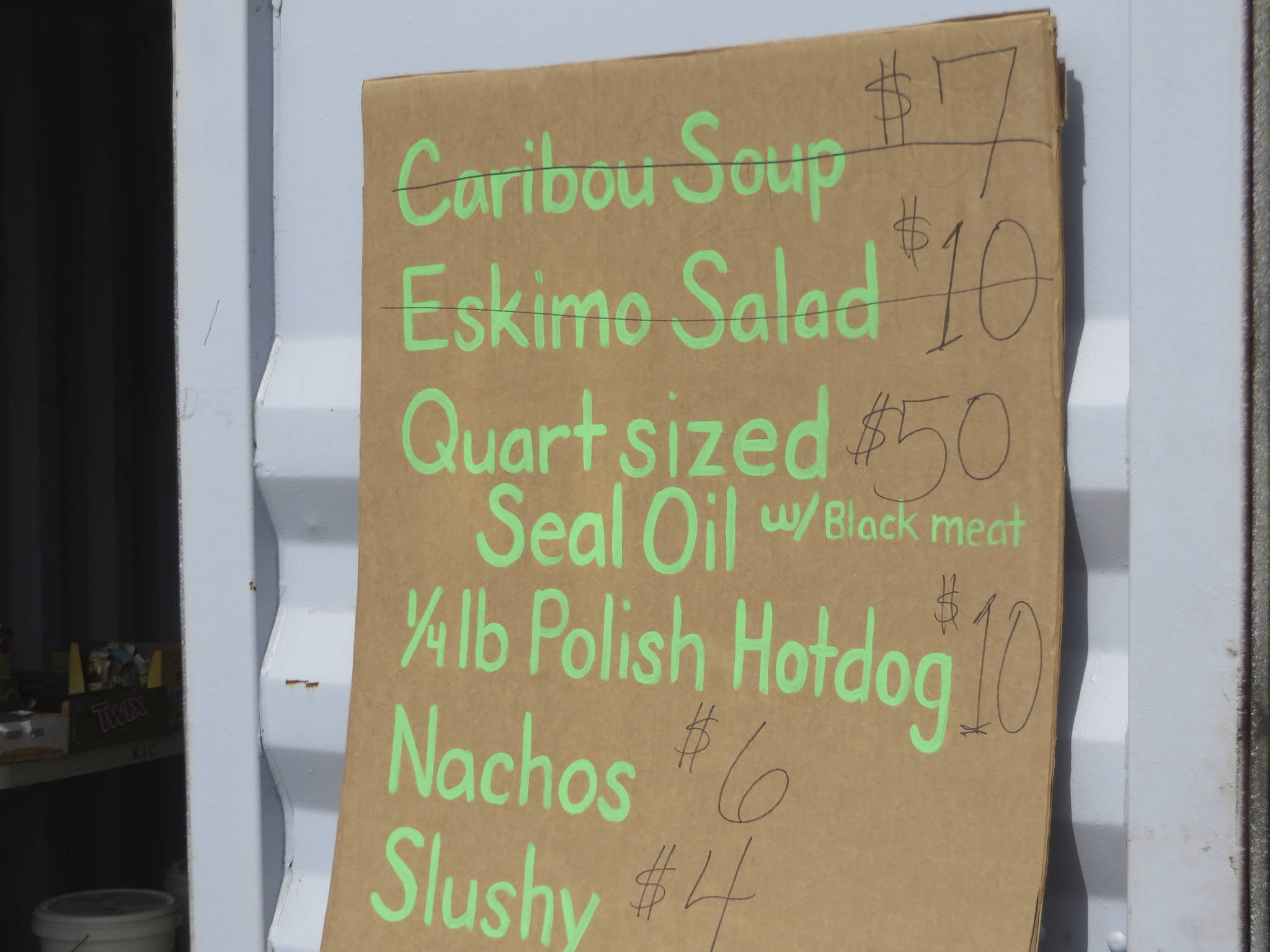

The oil — ever-present in households dotting Alaska coastlines — is used mainly as a dipping sauce for fish, caribou and musk ox. It’s also used to flavor stews and even eaten alone.

But when Inupiat elders entered nursing homes, they were cut off from the comfort food. State regulations didn’t allow seal oil because it’s among traditionally prepared Alaska Native foods that have been associated with the state’s high rate of botulism, which can cause illness or death.

That’s changing for 18 residents at Utuqqanaat Inaat — in English, a place for elders — a part of the Maniilaq Health Association in the Chukchi Sea community of Kotzebue, about 550 miles northwest of Anchorage. The association has worked with partners in Alaska and the Lower 48 to develop a process to kill the toxin in seal oil and make it safe for consumption.

Last month, Alaska’s Department of Environmental Conservation approved its use in elder homes, believed to be a first for seal oil in the U.S.

Maniilaq staff members and an ad hoc seal oil task force worked for more than five years with two universities to develop a way to eliminate the botulinum toxin without dramatically changing the taste or reducing the nutritional value of seal oil.

The effort began when Maniilaq was in the early stages of starting a traditional food program, said Chris Dankmeyer, its environmental health manager and a commissioned officer with the U.S. Public Health Service.

“The No. 1 crucial food that everybody wanted was seal oil, but we weren’t able to give them that,” he said.

Discussions were initiated to determine the safety risk of seal oil and possible ways to control it. Maniilaq staff worked with the task force, which included members across the state and nation, and that led to partnerships with the University of Alaska Fairbanks and its Kodiak Seafood and Marine Science Center, and with Eric Johnson, a botulism expert at the University of Wisconsin.

Most seal oil comes from subsistence hunters who are allowed by the U.S. government to harvest bearded, ringed and spotted seals in the Kotzebue area and to donate what they collect to nonprofits and other facilities.

Cyrus Harris, hunter support and natural resources advocate for Maniilaq, said ringed seals — the source of recent batches of oil — can weigh anywhere from 40 to 80 pounds. A smaller seal will produce 3 to 4 gallons of oil after the blubber, which accounts for about half of a seal’s weight, is rendered.

Botulism has always been controlled by heat, but the questions for those involved in the seal oil project were how high should the heat be and how long should it be applied to destroy the toxin.

“You know, we could boil it, but that’s going to change the whole characterization, the whole nutritional value of seal oil,” Dankmeyer said. “That’s not what we wanted.”

Seal oil was shipped to the University of Wisconsin, where it was spiked with different toxins and tested at varying levels of heat and lengths of time. Researchers discovered that heating seal oil at 176 degrees Fahrenheit for 2½ minutes destroys the toxins. To be extra safe, they decided to heat the oil for 10 minutes then keep it frozen so it doesn’t produce any additional toxins.

Harris said staff members at the Utuqqanaat Inaat facility must now be trained about safe handling, a process that is being slowed by the pandemic. Still, he expects seal oil will be available at the facility soon.

A driving force behind the research was Val Kreil, a former administrator of the nursing home. He made a promise to the elders that he would see the project through, even if he was no longer there. Two years ago, he moved to the Lower 48 but still maintained a presence with the project.

Now, Kreil wonders what additional uses the research could play in the safety of whale blubber and other traditional foods.

“After we were getting closer, we thought, my goodness, this could also help other people,” Kreil said from his home in South Carolina.

Elders at the facility, who range from their 60s to their 90s, have gotten tastes of seal oil in the past when relatives brought them food and it didn’t pass through the facility’s kitchen, where it would have been subject to state regulations.

But now the residents are excited about the prospect of having the oil anytime they want it, said Marcella Wilson, current administrator of the facility.

“They consider it a part of them, their being,” she said about the elders, recalling that some have said they “feel warm inside” and sleep all night after eating it.