On the far side of the room facing the audience stood an empty chair.

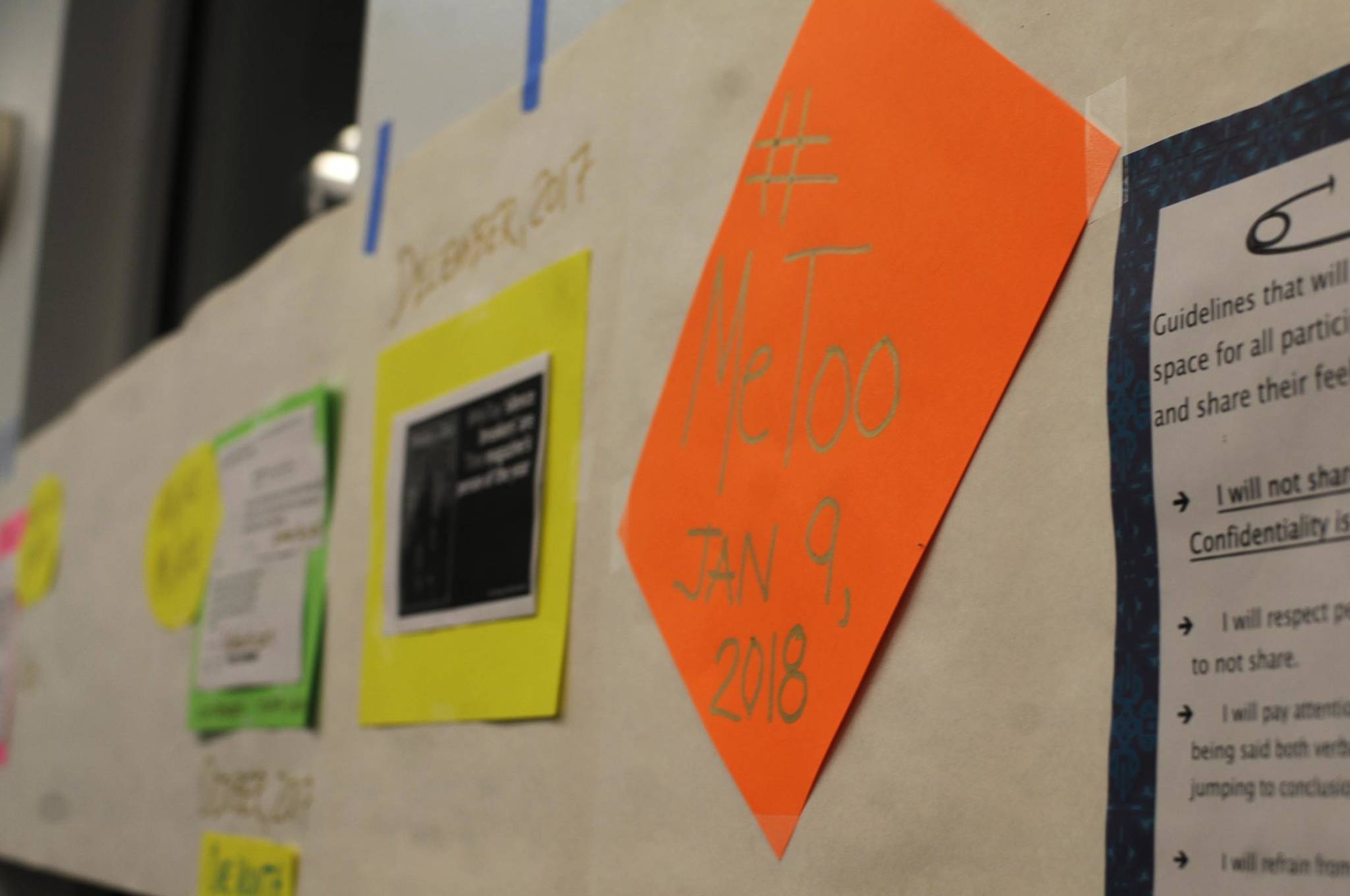

The organizers of the event at the Soldotna Public Library on Tuesday, which included a discussion of the “#MeToo” movement, placed it there to symbolize those not yet ready to speak up.

“Not everyone is ready to speak about these stories,” said Susan Smalley, one of the organizers for the event hosted by citizens’ group Many Voices. “Not everyone is able to speak about these stories. This chair represents those who are not in the room with us this night for whatever reason. We hold this place for them among us.”

Many Voices is a loose group of citizens who want to work on issues related to justice and unity in the community, Smalley said. The #MeToo event held Tuesday night was the first time they’d addressed the topic, and organizers were happy with the turnout, she said.

The #MeToo movement, the name given to an upwelling in public discussion of sexual harassment and violence toward women, gained national and international attention in October 2017. Millions of people used the Twitter hashtag to share stories of sexual assault and harassment in the wake of a New York Times investigation and subsequent stories documenting accusations against film producer Harvey Weinstein and a subsequent burst of accusations against public figures in a variety of industries.

Most of those gathered at the library Tuesday night were women, though the #MeToo movement has included men as well. A panel of five professional women discussed the impact of the movement and their thoughts on what its impacts are before the crowd broke into small groups to talk about experiences and solutions. Clinical therapist Pamela Hays, a member of the panel, said many women may have experienced sexual harassment without realizing it because it has been relatively normalized. The effects go beyond the experiences, too.

“I learned to behave in certain ways that wouldn’t encourage this type of behavior,” she said. “Then I thought about, ‘Well, wait a minute. Why should I have to modify my behavior to avoid something that’s wrong?’”

There has also historically been a stigma about bringing stories forward, which Hays said she’s seen with people in her practice. Kristen Mitchell, a local doctor who also spoke on the panel, said the long-term recovery from sexual harassment or violence can be a struggle as well.

“For some people, the pain and the injury can express itself physically as well as emotionally,” she said. “One of the things in my profession that is unfortunately underrecognized (is that) people who have pains and problems and challenges that somehow don’t make sense or we can’t quite explain on a medical basis may often have some kind of link to a trauma that somebody has experience in the past.”

Throughout the movement, a major theme is that each person’s story is their own and it’s up to them when they want to share it or not. There are risks to coming forward, too — at the highest level in the #MeToo movement, people expressed fear of repercussions at their jobs or in the community for making an accusation. In small communities, the echoes can bounce, too.

Smalley said for many of the people who choose to speak about an instance of assault or harassment, the goal might not be justice for the perpetrator, but rather closure.

“It’s not about bringing those people to justice, per se,” she said. “It’s about freeing up that in your own head that this did happen. … (People’s stories) are separate but they’re all part of the same cloth.”

That was part of the reason for the empty chair — to represent women within abusive relationships or who had experienced something they weren’t ready to talk about yet. Alaska has a sharp challenge within the domestic violence sphere — more than one in nine Alaskan women have experienced physical or psychological abuse within the last year, according to the University of Alaska Anchorage’s Justice Center. In past years, Alaska has shown some of the highest rates of domestic violence in the nation.

Stacie Larion, an advocate for survivors of domestic abuse with the Kenaitze Indian Tribe who spoke on the panel, said she has heard more than 200 stories from people about abuse in the past year. People can normalize abuse within their heads, which makes it harder to spot and harder for people to walk away from abusive relationships, she said.

“One thing I think that is of just utmost importance is educating future generations of our young people about what is a healthy relationship,” she said. “… Education is always an important part of working with clients. It takes a long time, sometimes, when people develop patterns.”

The LeeShore Center, a resource center and shelter for women and children who are victims of domestic abuse, is working on a domestic abuse and sexual assault prevention program through a state grant. The organization also runs a violence intervention education program called Green Dot, which is based on bystander intervention when “something is about to go sideways,” said Ashley Blatchford, the education and training assistant at the LeeShore Center.

“Green Dot will give you the ability to identify red flags by behaviors from the point of view of a bystander, because it’s not always going to be you in it — sometimes it’s going to be others — and what kind of things that you can do,” she said. “It gives you real hands-on tools.”

Leeshore provides the Green Dot training to any organization that requests it. Smalley said Many Voices would be happy to do the training, as it fits with the group’s mission.

Many Voices has conducted several awareness walks, including a walk connected to the national March for Women last January, and one as a fundraiser for the victims of Hurricane Harvey in Texas in August 2017. They’re planning another Walk for Unity and Justice on Jan. 20 in Soldotna at 12:30 p.m., starting from the parking lot of the medical building next to the Soldotna library.

The organizers try not to be “anti-anything,” Smalley said, but want to focus in part on what people are doing to help bridge some of the divides in the community.

“We’re going to coalesce around (the Green Dot training) because that seems like a natural thing for us to do,” she said. “We kind of look for the things that people raise up … part of it is education about what’s going on in the community because we have a tremendous number of things going on in the community because even if you’re in the middle of it, (it’s hard to see everything).”

Reach Elizabeth Earl at elizabeth.earl@peninsulaclarion.com.