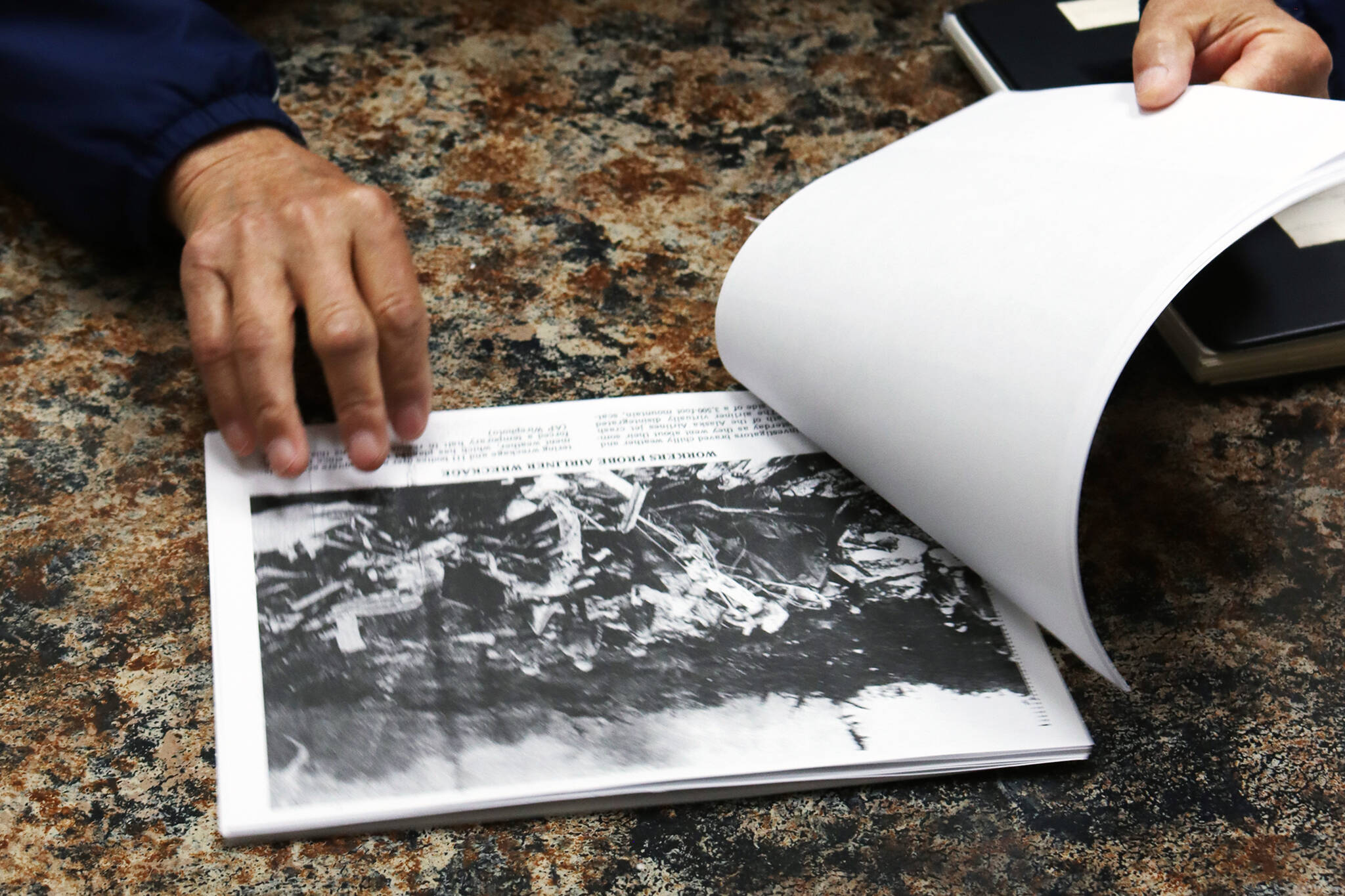

The crash of Alaska Airlines 1866, the deadliest in Alaska’s history, and, at the time, the country, led to changes, including the integration of a new set of navigation specifications, tested in Alaska, to prevent future crashes.

At least one man wants to remember those National Guardsmen who volunteered to help out 50 years ago, before it was even known if it was a search and rescue or recovery.

“It was kind of ironic. I had to go to Anchorage that week,” said Charlie Smith in an interview. “I came back on Friday. I still had my ticket that had me coming home on that flight the next day.”

Smith, then a National Guard first lieutenant leading the 910th Combat Engineer Company of the Alaska Army National Guard, recounted his experience of the crash as guardsmen helped out state and federal organizations in treating the dead and investigating the crash. The crash, caused by incorrect navigational information, according to the National Transportation Safety Board, resulted in the death of 104 passengers and seven crew aboard an Alaska Airlines Boeing 727.

Rapid mobilization

When the plane was lost to communications, authorities were notified as a part of the emergency procedures, including the Alaska State Troopers, whose purview includes all search and rescue operations in the state.

“The troopers were actually in charge. Back in those days, we didn’t have SEADOGS or (Juneau) Mountain Rescue. It was the troopers and the guard,” Smith said. “The Coast Guard was pretty active. They talked about bringing a helicopter in, but they couldn’t because of the weather.”

Alerted by Alaska State Troopers Capt. Dick Burton, Smith asked for volunteers from the National Guard to assist at a time when they didn’t know the parameters of the mission.

Smith recalled the conversation he had with Burton: “‘Hey, Charlie, we got a plane late and we don’t know where it’s at. Could you call out some of your guys to help search?’’

“I called all my officers and sergeants in,” Smith said. “I got 41 people to volunteer. We coordinated with the troopers.”

The National Guardsmen weren’t technically activated at that point, Smith said, but later, an order by then-Gov. William Egan retroactively stood the unit up.

“Within an hour, I had my chain of command activated,” Smith said in an interview. “We got underway that day.”

Weather had flights socked in, Smith said, so the guardsmen rode on a Coast Guard cutter out to the area where the crash was believed to have occurred, not far from Howard Bay. After setting up a base camp, guardsmen walked up the slope into the clouds and fog to find where Flight 1866 had terminated. Three witnesses had heard the plane fly overhead or the explosion, according to the NTSB report, giving them an approximate location.

“It was a typical Juneau day — you couldn’t fly in there,” Smith said. “My guys climbed up the mountain — that’s a long climb.”

A gruesome crash site

While authorities had an approximate location, they needed to localize it first, Smith said.

“They knew approximately where it was. We spread out and started walking out,” Smith said. “We found the crash site. On top of all the bodies, there was 600 pounds of moose meat scattered around.”

The mixed remnants spread over the side of the mountain were a grim sight for the guardsmen responding to the crash, Smith said. The moose was from a hunt elsewhere in the state, being carried by the plane in the cargo section.

“There was some gruesome stuff up there. You don’t really want to remember that kind of stuff,” Smith said. “Sometimes, the body bags had moose meat. We were there until all the bodies were picked up. That was probably two weeks.”

Other organizations, including the troopers, the Federal Aviation Administration, and even the United States Postal Service were involved in the investigation, but the National Guard did their share of the initial recovery operations, Smith said.

“The guys, the stuff they had to put up with — we all put up with some pretty nasty stuff,” Smith said. “We had gloves on and stuff, but when you’re picking up pieces of a young person’s body, it’s a difficult thing to do.”

Assisting the authorities

While some guardsmen were responsible for removing the mortal remains of more than 100 people from the crash site, others guardsmen helped the responding agencies organize body parts for identification at the National Guard armory downtown, now the Juneau Arts and Culture Center.

“It was a morgue. There were several of my guys helping out who didn’t have a problem with what they were seeing or doing,” Smith said. “Some of the other guys were out with the helicopters helping carry the bodies.”

The morgue was used to identify the victims, who were often rendered unrecognizable or even mixed with the remains of other humans or animals by the force of the impact.

“The FBI guys brought in three refrigerator vans and set them up right behind the armory,” Smith said. “It was not a fun job. We got all that done. The armory was used for probably two months altogether.”

The armory interior had to be entirely stripped down, sterilized and refinished when the operation was completed, Smith said. Smith touted his men for doing the work they did, far from home at the site of a terrible tragedy.

“You could walk around there but it wasn’t easy. I didn’t spend the time most of my guys spent up there. I spent a lot of time at the armory,” Smith said. “They put up with a lot of stuff.”

Hard work by volunteer guardsmen

The crash was determined by the National Transportation Safety Board to be the result of misleading navigational information, which led the pilots to descend from cruising altitude too soon, and crashed into the mountain at speed.

“There’s a lot of stuff left up there,” Smith said. “It hit hard. I think they estimated it was doing 250 miles per hour.”

While the guardsmen had helped out with flooding and smaller crashes, the group had never dealt with something of that scale, Smith said.

“I think they did very well,” Smith said. “They said, we have a job to do and we’ll do it.”

Contact reporter Michael S. Lockett at (757) 621-1197 or mlockett@juneauempire.com.