Alaska faces a paradox with its health care industry.

In an economy sliding downhill, health care is the only sector still growing. With many jobs that pay solid wages and a growing need for medical services, in some ways it is encouraging even as other high-paying jobs in the state are lost.

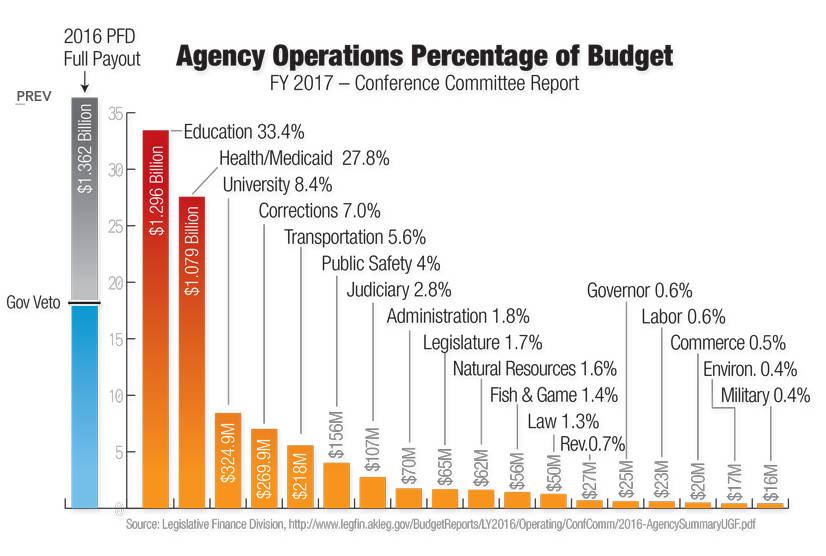

However, health care is also one of the top costs to the Alaskan government and a heavy burden for many local municipalities and businesses. As it continues to grow, with more employees and more income, it is worrisome for employers and public agencies, who pay the vast majority of health care costs in the state.

To try to trim away at some health care costs in the FY2018 budget, Gov. Bill Walker upped premiums for state employees’ health care, avoiding an approximately $8 million increase in costs, according to the Office of Management and Budget’s summary.

“The Governor recognizes the negative impact this will have on lower paid state employees, but it is necessary for the state to make changes that are equal in measure to the challenge,” the summary states. “To demonstrate that change in government must be wide spread and significant, Governor Walker is reducing his own salary by one-third.”

The Senate and the House of Representatives approved a Medicaid reform bill in 2016 and have been sorting through Health and Social Services’ expenses this year, looking for places to cut. The Senate’s budget, passed April 16, proposes millions in cuts to the department, while the House of Representatives proposed a small increase. Changes at the federal level under the American Health Care Act, recently approved by Congress and awaiting hearings in the Senate, may mean changes for the Medicaid program, including requiring the state to shoulder more of the cost.

After Walker accepted the Medicaid expansion in early 2015 under the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, the state began receiving millions from the federal government to prop up the Medicaid program under the additional enrollees. Now, with Republicans in charge of Congress and the White House, the American Health Care Act may roll back that support, leaving the state on the hook to either drop all the additional enrollees or pick up the multi-million-dollar bill.

In February, when Congress was debating the first version of the bill, Alaska Department of Health and Social Services Commissioner Valerie Davidson formally said the state couldn’t bear the cost shift.

“With a $3 billion budget deficit in Alaska, we simply cannot absorb a shift in federal responsibility to states,” Davidson said.

Mouhcine Guettabi, an assistant professor of economics with the University of Alaska Anchorage’s Institute for Social and Economic Research, researches both the health care industry and state government spending. It’s sometimes an interesting juxtaposition, he said.

“At times I present (economic) forecasts … and the only field we’re relying on is that health care is still growing,” he said. “And I’ll go to the next room and rail about health care costs.”

Medicaid growth, federal dollars

Alaska’s health care industry, with some of the highest costs in the country, is an isolated bubble. While other states’ hospitals and clinics draw medical tourists from out of state, bringing in additional money to their economies, Alaska sees the reverse. Many health care plans pay for medical tourism — flying a patient down to hospitals in the Lower 48 to receive treatment and reimbursing the costs of hotels, food and flights along the way, because it is cheaper to do so than have the same surgery in-state. So the fiscal growth of Alaska’s health care industry is coming entirely from the pockets of insurers and companies based here, Guettabi said.

Many of Alaska’s people also rely on federal dollars for their health insurance. Besides those receiving Medicare, Tricare and Indian Health Services benefits, Medicaid in Alaska is in part paid for by the federal government and 90 percent of those who purchase individual plans from Premera Blue Cross Blue Shield through the Affordable Care Act marketplace receive federal subsidies, according to a research summary published by ISER in April 2017. Altogether, about 53 percent of Alaskans have employer insurance, and about 9.2 percent of Alaskans still report being uninsured, according to the summary.

“Employer insurance is still the most common, covering half of all Alaskans,” the summary states. “But fewer small businesses are offering it.”

The actual costs of health care services increase every year, leaving it up to commercial insurers to raise premiums and public insurers to either raise taxes to cover the cost increase or to lower the percentage of a price they reimburse doctors for. The lower reimbursement rates for Medicare and Medicaid relative to private insurers affect providers at all levels. Alaska has not lost any of its rural hospitals yet, unlike the Lower 48, but they feel the lower reimbursements, said Becky Hultberg, president and CEO of the Alaska State Hospital and Nursing Home Association.

“From a hospital standpoint, doing more with less can mean a reduction in rates, utilization or eligibility,” she said. “When the decision to do more with less means lower rates, that is just asking hospitals to do the same thing for less money, which essentially is just squeezing the balloon.”

The federal administration and some in Congress are also looking to reform Medicare, a growing program as the population ages. Among the Alaska State Hospital and Nursing Home Association’s 2017 legislative priorities are goals to preserve Medicaid reimbursement rate stability and look for new payment models, strengthening policies to support the growth of the individual insurance market and advocate for Alaska-specific solutions for Medicaid coverage for low-income residents, according to its website.

Reform

In June, the Alaska Legislature is due to receive a feasibility study on the formation of an Alaska Health Care Authority, which would oversee the implementation and expenses of the Medicaid program. Among its functions could be running a single health care plan for state employees and retirees, with the potential for expansion to private individuals and businesses — fundamentally a single-payer insurance program for Alaskans.

Pat Linton, former executive director of the Seward Community Health Center, said he spent 40 years working in health care and watched its share of the national gross domestic product triple as costs rose out of control. The cost is only likely to increase as the population ages and public health continues to be poor, despite how much the health care system costs. Socioeconomic status, proposed by many researchers as a major determinant of health, is not recovering for many of the poorest people nationally and until it does, health care delivery is not going to solve many widespread health problems people see, he said.

Linton, who also served on the Kenai Peninsula Borough’s Healthcare Task Force in 2015 and 2016, advocates for a national single-payer system, which he said would at least simplify the currently complex health care insurance system.

“Scrap this — transition to a single-payer ‘Medicare for all’ system and it will at least do probably better than we’ve been doing through this hybrid, hodgepodge of market based (and) public-based, just this cacophony of things,” he said.

Hultberg said it’s too early to say what the effects of an Alaska Health Care Authority might be, but that the Alaska State Hospital and Nursing Home Association will provide comments on the study when it is released.

The current status of the health care industry, growing beyond what anyone can afford, is clearly unsustainable, Guettabi said, but just how big it can grow is unclear. Until there’s an incentive for providers to change the system, they won’t be motivated to move toward reducing costs, which means reducing profits as well. And the question of better health outcomes is a separate one entirely — it’s easy to get inexpensive systems or systems that produce good results, but finding one that meets both is the challenge.

“The state is trying to save money,” Guettabi said. “Is it trying to maximize the health of its citizens? I have no idea. The hospitals are trying to maximize their profits, if it’s a for-profit (hospital). The individual is trying to save money. We all have different objectives. It’s not like we’re all in this together.”

Reach Elizabeth Earl at elizabeth.earl@peninsulaclarion.com.