Annie Boochever knew there needed to be an Elizabeth Peratrovich biography, but the author and former Juneau resident wasn’t sure she should be the person to write it.

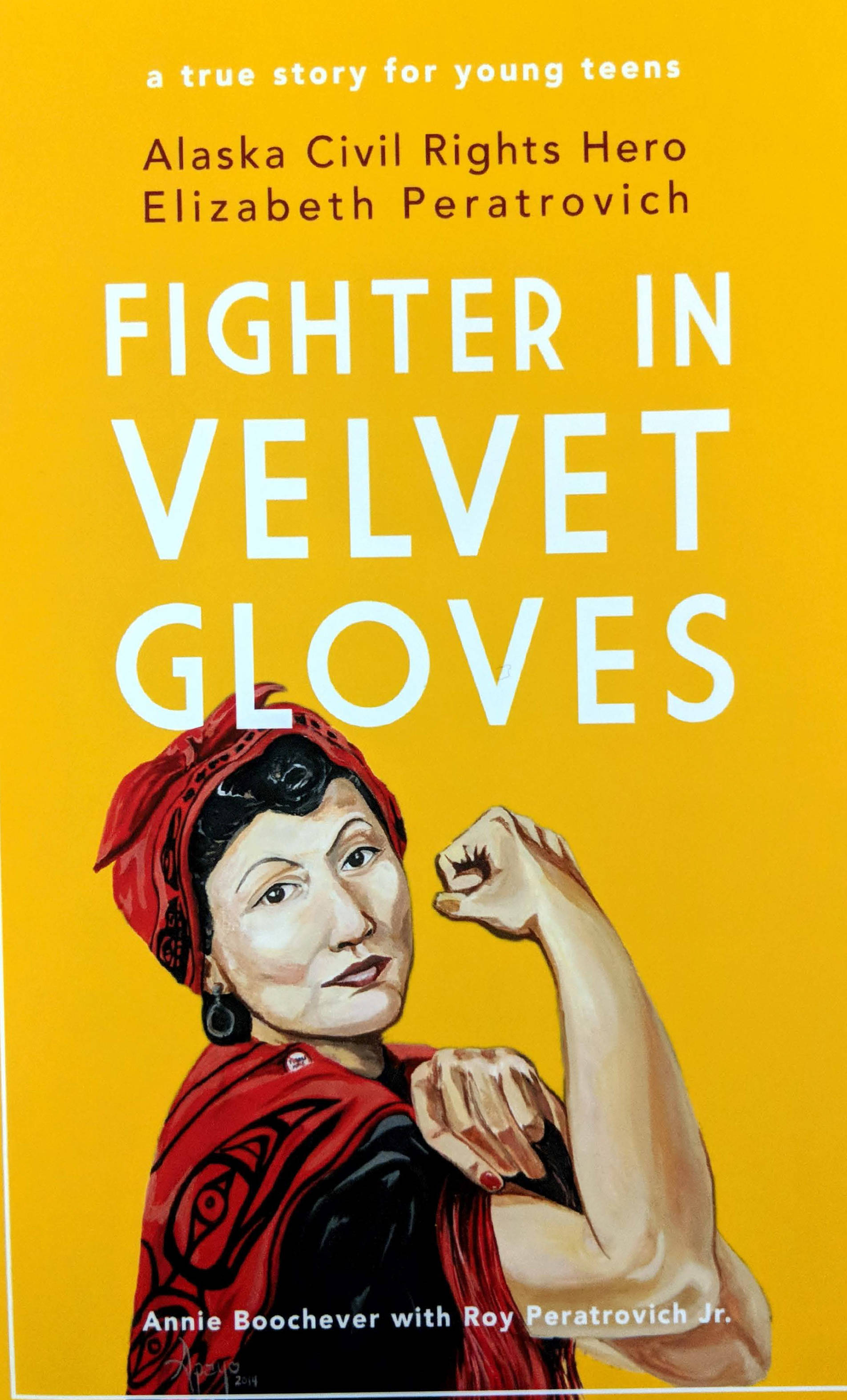

However, when Boochever’s book, “Fighter In Velvet Gloves: Alaska Civil Rights Hero Elizabeth Peratrovich,” written with Roy Peratrovich Jr., came together, it was apparent growing up in Juneau and living in the capital city for decades gave Boochever first-hand insight into many of the places and people Peratrovich encountered while fiercely advocating for Alaska Native civil rights and delivering testimony that helped lead to the 1945 passage of Alaska’s Anti-Discrimination Act.

“By the time I got all the information, by the time I was finishing writing the book, I was completely blown away by the fact that I knew almost every single one of the important players in the passage of that bill,” Boochever said during an interview with the Capital City Weekly. “It’s like it was meant to be.”

Boochever’s time in Juneau also meant she was well aware of the significance of Elizabeth Peratrovich’s advocacy and the systemic obstacles that would have stood in the way of a Tlingit woman in the first half of the 20th century.

“I grew up here, and I was very aware of the prejudice and the racism,” Boochever said. “Not to the extent that there was before the anti-discrimination bill, but I grew up in the ’50s and ’60s, and I saw it in the schools. I saw it with my classmates, and it really bothered me.”

[Alaska Natives want voice in budget-making process]

Her experience teaching in schools also factored into the decision to ultimately write the book for teens released in February.

While working as a librarian and music teacher in Juneau, Boochever realized there were few educational materials that told stories from an Alaska Native perspective. Boochever said she worked with culture bearers from various communities and adapted stories and songs into musical plays.

When Feb. 16 was designated Elizabeth Peratrovich Day, in 1988 Boochever said she encountered a familiar problem.

“It became very clear that there were very few resources,” Boochever said. “In 2014, my first book came out, ‘Bristol Bay Summer,’ and I decided to retire from teaching then, so I could devote more time to writing. A lot of colleagues said,’You’ve got to do a book about Elizabeth Peratrovich, but we need a book about her.’

While Boochever found the idea tempting, she did not know any direct descendents of Elizabeth Peratrovich.

“I wouldn’t dream of doing a book like that without working with the family,” Boochever said.

But not long after retiring, Boochever’s niece introduced Boochever to Roy Peratrovich Jr., Elizabeth Peratrovich’s son.

Boochever said he was eager to talk about his mother, and she soon began to find out more about the day-to-day life of an Alaska icon.

She said Peratrovich was as smart, fearless, well-spoken and determined as one would have to be to transcend the restraints of racism and sexism to effect change.

“She was very smart,” Boochever said. “She was so articulate, and she learned to do it and still be very graceful. She wasn’t combative, and I think because of that when she walked up to the Territorial Legislature to deliver her testimony, I think people were probably astounded.”

[Alaska Native weaving project honors survivors of violence]

Research and conversation also filled in some lesser-known details about Elizabeth Peratrovich’s life, including the unusual, still somewhat mysterious relationship between her birth parents.

“Online, almost everything about Elizabeth Peratrovich, Wikipedia and all that, they kind of gloss over her birth,” Boochever said.

However, the circumstances of her birth and subsequent adoption profoundly shaped Elizabeth Peratrovich’s life.

Her biological parents were Irishman William Paddock and Edith Tagcook Paul, who were unmarried. Things were further complicated because Tagcook Paul began living with Paddock after her sister and Paddock’s wife, Anna, contracted tuberculosis.

“It was customary at the time that if there was a family member that could move in with the children, that’s what happened,” Boochever said. “Nobody knows the relationship between William and Edith, but we know that she got pregnant, and having no way to take care of the baby, she went to Petersburg and had this little baby and gave it up to the Salvation Army for adoption.”

The baby girl who would grow up to be Elizabeth Peratrovich was soon adopted by Andrew and Jean Wanamaker, a Tlingit couple from Sitka.

[Sitka could be heading to the small screen]

“She grew up the Alaska Native way — subsistence lifestyle, spoke Tlingit fluently,” Boochever said.

Her mother was an acclaimed weaver and her father was a lay minister who traveled around Southeast Alaska, which Boochever said taught a young Elizabeth Peratrovich the value of words.

“Later, she would come back to those same little towns and preach about civil rights,” Boochever said.

Speaking to Roy Peratrovich Jr., Boochever said she also learned about the deep vein of compassion that ran through his mother. Boochever said the anecdotes didn’t change how she thinks of Elizabeth Peratrovich but added depth to a figure who is sometimes reduced in collective memory to her important testimony.

“I was in awe of how much actually she had done,” Boochever said. “Plus, getting to know her as a human being, too. Roy told me stories about her that were very, very sweet. He said for a while in high school, all of his buddies couldn’t wait to go to his house after school because she was reading ‘The Hunchback of Notre Dame’ to them.

“She was very generous, ” she added. “She had a big heart. She would invite in all the stray cats in the neighborhood, Roy said. At one time, he remembers the entire Sitka basketball team sleeping at their house. She just sounds like a wonderful person.”

• Contact arts and culture reporter Ben Hohenstatt at (907)523-2243 or bhohenstatt@juneauempire.com. Follow him on Twitter at @BenHohenstatt.