Four sentences written nearly two centuries ago by a homesick man on a lonely California beach are being used in the efforts to revive the fading Dena’ina language.

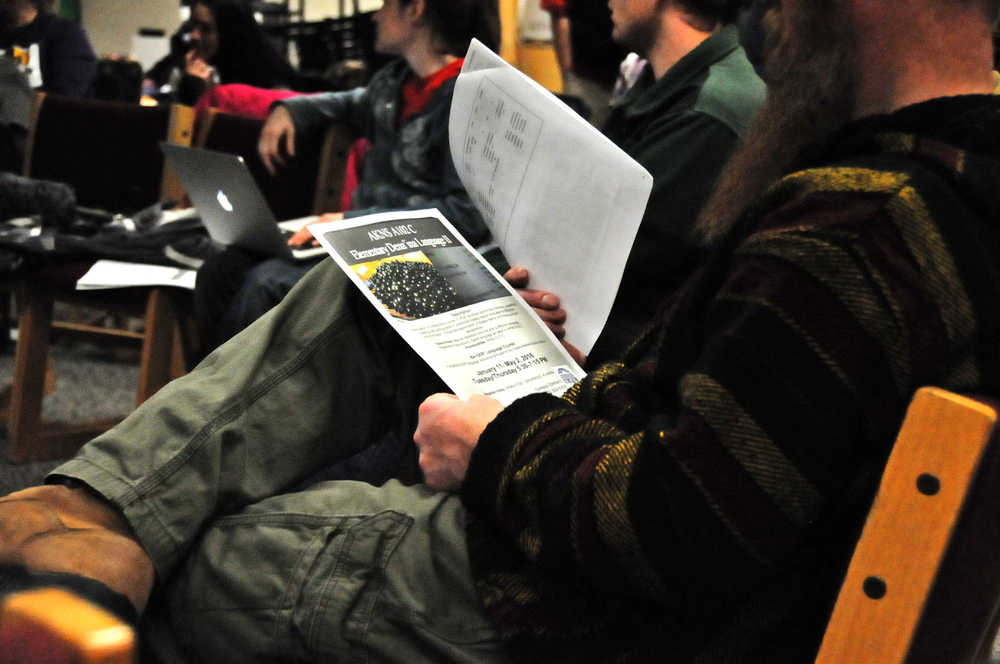

A group of people gathered around a screen in the McLane Commons of Kenai Peninsula College listened carefully to the humming of a four-line song, a man singing the Dena’ina words of his ancestor. The group, many of Alaska Native descent but many of other ethnicities, struggled to follow along with the audio from the printed words in their hands.

The Kenai Peninsula College hosted a forum Thursday to introduce the public to the basics of the Dena’ina language, including a brief lecture on verbs and the aspects of the language that differ from English.

The Native language of much of Southcentral Alaska, including the central Kenai Peninsula and across the Cook Inlet, has been gradually fading from regular use for the last century. It is estimated that fewer than 100 people speak the language today. Teachers at Kenai Peninsula College and members of the Kenaitze Tribe hope to save it from dying out completely.

Kenai Peninsula College and the University of Alaska Anchorage offer basic Dena’ina classes. However, because there are so few fluent speakers, even the teachers are learning.

Sondra Shaginoff-Stuart, the Rural & Native Student Services Coordinator, speaks some Ahtna and some Dena’ina but is learning alongside her students, she said. An elder from Lime Village in Southwest Alaska who is a fluent Dena’ina speaker has been attending her class this semester as a language aide, she said.

The remoteness of some villages has preserved the language there — the closer villages are to the road system, the more the Native languages die out, Shaginoff-Stuart said. Some workers are going out to document the language from the native speakers in the more rural areas, she said.

“Most of our road-system languages are gone,” Shaginoff-Stuart said. “A lot of the (Kenaitze) language is gone, along with my language, Ahtna. The closer you are to the road, you don’t see the language used as much. If you go across the water, away from the road, there are more fluent speakers.”

But the interest on the Kenai Peninsula is clearly there — the Kenai Peninsula College class tends to fill its seats while the class at University of Alaska Anchorage does not, she said.

The college is able to teach the classes through the works of Peter Kalifornsky, one of the last fluent Dena’ina speakers of the Kenai dialect. Although Kalifornsky died in 1993, Dr. Alan Boraas, who worked with him to publish dual-language versions of Kalifornsky’s short stories in 1991, teaches Dena’ina basics at Kenai Peninsula College.

Boraas is not fluent, either. His background is in anthropology, not linguistics, but he said he understands the language well enough to teach its essentials. Boraas, an anthropology professor at the college, will teach the second installment of the Dena’ina class in the spring with Shaginoff-Stuart.

“The sentences we’re going to be putting together, those will be like the Dick and Jane books,” Boraas said. “Not complicated by any means.”

Boraas said he is optimistic that Dena’ina can be revived, but there is a deadline — all the fluent speakers are elders, and many live in remote areas. If the efforts to revive the language do not succeed relatively soon, the elders may die off before any younger speakers become fluent.

Steven Holley, who grew up in Tyonek, said he knows some Dena’ina from his childhood. However, he doesn’t think in the language except for a few words, which still makes it a second language for him, he said.

“I’ve always had an ear to listen for it,” Holley said. “I’ve always heard it. There’s only two words that when I hear it in English, I think it in Dena’ina. It shouldn’t be that way.”

Holley, who currently lives in Anchorage, said he is working on developing an app to introduce the language to more people.

“I’m trying to learn more so we can build more content,” Holley said.

Boraas said one of the main reasons to restore the language is to restore the though patterns that accompany the language. Every language’s grammar is subconscious, which connotes different patterns of thinking. In Dena’ina, the sentences are built around the verb, placing more importance on action rather than the subject, he said.

“Communication is happening in fewer and fewer languages,” Boraas said. “If it is true that there are patterns of thought that are embedded in the grammar of languages, and we are using fewer and fewer languages, we are losing patterns of thoughts. In the same way that when a species becomes extinct we lose genetic diversity, when a language goes extinct, we lose cognitive diversity.”

Shaginoff-Stuart, who was a student in the first Dena’ina class and went on to become a teacher, said the goal is to restore the language enough to allow the native speakers to communicate in either language and be understood.

“The basic goal is to bring back the language into home use, into the families, not so much into the government,” Shaginoff-Stuart said. “They don’t want it to go away. They talk about how in my lifetime, our language could go.”

Reach Elizabeth Earl at elizabeth.earl@peninsulaclarion.com.