After a college career in wrestling and years of teaching the sport to youngsters as a coach in Seward, 55-year-old Ronn Hemstock never expected to compete in the match of his life on the tarmac of an airport on a pitch-black Alaska morning.

But that’s what happened when a large brown bear — possibly up to 900 pounds according to Hemstock and a friend’s calculations — barreled down the runway of the Seward Airport on Oct. 27 and knocked him off his feet.

“I was out walking my dog,” Hemstock said in a recent phone interview. “My normal routine every morning.”

As fall encroaches on Alaska, the sun rises later and later. By late October around 6 a.m., about the time Hemstock hit the runway, it wouldn’t be up for a few hours.

An avid pilot and Seward resident of more than two decades, Hemstock keeps his own plane at the airport and uses the early morning walks with his dog as a way to keep it cleared of snow in the winter, as well as clearing debris and small animal carcasses off the runway. He describes the morning ritual as somewhat of a public service.

Hemstock was in his “own little world,” on the phone with his brother to discuss the details of his daughter’s upcoming wedding when his dog tore across the runway out of the darkness, he said. It ran right between his legs, tail tucked and hackles up. That’s when it hit Hemstock that his dog was “running for his life,” he said.

Something wicked this way comes

The last thought the coach and shop teacher had before he turned around was, “I hope it’s a moose.” But there was no such luck.

Hemstock described watching the brown bear’s body undulating toward him.

“I could only see its outline silhouetted by the light,” he said.

He had just enough time to turn and begin to run before the bear, which Hemstock originally thought was a sow but now suspects was a male, was on top of him. He remembers feeling intense pressure but no pain as the bear bit down into his right shoulder, with another two teeth sunk into the back of his arm. At that point, the bear picked him up off the ground and shook him “like a rag doll,” Hemstock said.

The bear bit into Hemstock about five or six times during the attack, he said.

“It clawed the hell out of me and it rolled me over,” Hemstock recalled.

It was when the bear began to attack his stomach that Hemstock really started to worry. He wasn’t about to sit there and “watch it eviscerate” him alive, he said. Throwing caution and fingers to the wind, Hemstock stuck his hands in the bear’s mouth, then managed to roll back over onto his stomach.

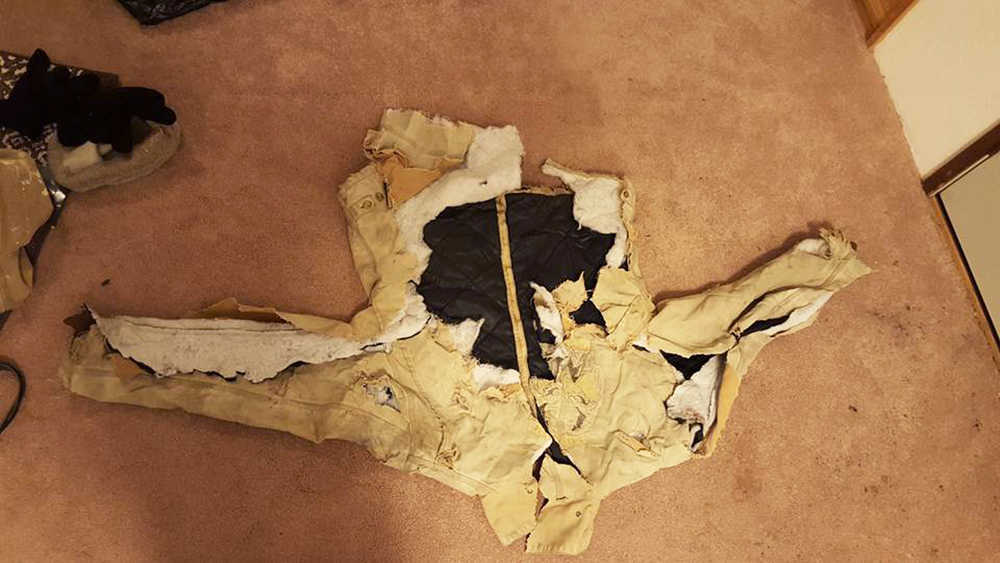

Hemstock credits his preparation for that morning’s walk as a factor in his being alive today. In addition to his Carhartt jacket, the coach had donned a long sleeved shirt and two sweatshirts to protect against the crisp morning air. While the bear attempted to rip into his back, Hemstock said he could hear it gritting its teeth and working away at the clothes.

“I was thinking, ‘God, I’m really glad I dressed like this,’” he said.

A large section of the back of Hemstock’s coat was completely torn away. Upon returning to the scene of the fight, however, he said he wasn’t able to find any material scraps, which leads him to think the bear was literally eating through his clothes to get to him. Luckily, Hemstock’s still covered in the winter gear department — Carhartt sent him a new coat after he sent them a picture of his own, post-attack.

The bear finished its attack on Hemstock by jumping on his back, he said. He laid still on the runway, debating how long he should wait before getting up in case the animal was still around. When he felt his dog licking him in the face, Hemstock said he judged the coast was clear.

In a moment of what he describes as pure clarity, Hemstock dialed 911 instead of the number for the local police, as he knew his phone would be tracked by GPS if he was routed through the dispatch center in Soldotna, about 90 miles away. He was worried the bear might come back for an encore and end up moving him, he said. Before calling the authorities, though, Hemstock called his wife, Jill, who he said knows exactly where he takes his morning walks and where to find him.

“My wife was just phenomenal,” he said.

Police later told Hemstock that in their rush to reach him at the airport, they found themselves stuck behind a car that wouldn’t pull over to let them pass. Sure enough, he said officers realized it was his wife when the car pulled into the airport ahead of them, beating them to her husband.

“She was just cool as a cucumber,” Hemstock recalled.

Business as usual

Hemstock said he was rushed into surgery in Anchorage via helicopter, with his arm in the most serious condition. Aside from numerous stitches and staples, and he suspects a few broken ribs, he emerged from the mauling largely unscathed. In fact, even though a chunk of muscle was so damaged it had to be removed from his arm, Hemstock was back at work the very next day.

He had a wrestling tournament to run, he explained.

Aside from that missing muscle in his arm, Hemstock is still the man he was physically, he said. He doesn’t expect his injuries or his experience to cramp his coaching style when it comes to wrestling. In fact, the ordeal may just help it, he said.

Members of his wrestling team now view him as something of a “super human,” Hemstock said. What’s more, none of the boys he coaches have a legitimate excuse to sit out of a practice anymore, he joked. If Hemstock could be back at work in a day after being mauled by a bear, the boys can wrestle through less, he said.

The teaching community in Seward was supportive after the attack, Hemstock said. Some visited him in the hospital and one even stayed with his wife and daughter.

Hemstock went back to the airport the day after the attack to retrieve a pair of glasses he had dropped, he said. That’s when he looked around for the evidence of his clothes being ripped to shreds. Police and wildlife authorities later told Hemstock they saw tracks in the snow during their investigation that suggested the bear had been chasing after his dog before it found him.

Hemstock then got busy trying to size up his opponent. He measured the distance between the bite marks in his back to get an idea of the bear’s dentition, he said. In comparing those measurements to bear skulls that belong to a friend of his, Hemstock and his friend think the animal was upward of 900 pounds. This is what makes Hemstock think he was attacked by a male bear, but he said he won’t know for sure until DNA test results come back from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

Fish and Game biologists told Hemstock they keep a running catalog of bear attacks, including DNA evidence. Being able to compare the DNA of one bear involved in an attack to that of other bears can help them determine whether they have a “problem bear” that has attacked more than once on their hands, he said.

Nefarious neighbors

Hemstock’s attack was not a one-off this year as far as bear activity goes in Seward. The coastal community had been having problems with bold brown bears coming into town as recently as a week before he was mauled.

“The week I was bitten, they killed (three) bears and there were at least four more bears in Seward,” Hemstock said.

The Alaska Dispatch News reported that a sow and two cubs were shot and killed over the course of two separate incidents the week of Oct. 16-22, while raiding backyard chicken coops. Another bear cub was shot at that week but was not found dead or alive.

An 18-year-old Seward High School student also had a run in with a black bear in early November while walking home from school. The student was not hurt, but the bear made off with his lunch, a Hot Pocket.

While brown bear activity has been relatively quiet elsewhere on the Kenai Peninsula this year, a series of attacks in quick succession had wildlife investigators busy in 2015 — a man walking his dog in Sterling, a young woman jogging along a trail near Cottonwood Creek on Skilak Lake with a coworker, and a Texas hunter stalking moose with his brother at Doroshin Bay, also on Skilak Lake. All three became the victims of bear maulings when they startled nearby bears, according to wildlife authorities. All three survived.

A firefighter was also mauled but not killed while battling one of the lightning-sparked fires in Cooper Landing in 2015.

Hemstock said he suspects heightened bear activity in Seward this year has had something to do with changes in the hunting policy on the peninsula over the years.

“You never saw brown bears in Seward when I moved here 20 years ago,” he said.

He also cited low fish runs this year as a reason bears may have been particularly hungry and therefore more willing to stalk chicken coops.

The attack has done nothing to sour Hemstock toward his daily morning walks — other than a little post-traumatic stress, he said — or his largely active lifestyle. He’s been an avid hiker for 20 years and has never had a similar bear encounter before, he said.

“It’s made me consider life as more worth living,” Hemstock said.

Reach Megan Pacer at megan.pacer@peninsulaclarion.com.