The longest-tenured instructor at Kenai Peninsula College at time of his retirement in 2002, Boyd Shaffer once described himself this way: “I get started on a nature thing or an art thing, and look out. There’s no stopping me. That is what I am.”

His love of art and nature—plus his enthusiasm and ability to teach—propelled him to a 37-year relationship with the college, first as a popular adjunct and then as one of its first full-time faculty members.

Shaffer died June 25 at 90 after a battle with cancer.

Talented at art and deeply curious about nature at a young age, Shaffer sketched what he observed. In and around his hometown of Salt Lake City, he examined structures and painstakingly recorded them on paper. He pulled apart plants and drew their contents. With the help of neighborhood specialists, he also learned the arts of taxidermy and falconry.

“I started to find as I grew up that there were too many things I didn’t know,” he said. “So I started reading books—about every living thing, about every kind of animal. By the time I was 12 years old, I knew every bird in Utah by sight and was a member of the Utah Audubon Society. I was (also) a taster. I tasted everything. I was eating all my mother’s nasturtiums before I even knew they were edible. I could live off the land when I was 16 years old.”

Shaffer also discovered early on that he enjoyed imparting his knowledge: “I started lecturing to kids in my neighborhood when I was about 10 years old. I’d learn something out of my books, and I’d go out and they’d gather around me and I’d talk about this plant or that plant or that tree, what it was all about.”

By 12, he was a guest lecturer on bird behavior and identification at the University of Utah. In his teens, he led tours for the world-famous Tracy Aviary in Salt Lake City.

At 18, he was drafted into the U.S. Army, and he served in the European theater during World War II. After he was shot in the leg in the Battle of the Bulge in France, he convalesced in Paris and refocused on his passions by studying fine art at Sorbonne University. In his late 20s, he was hired as a naturalist consultant by the Walt Disney production company and worked as a wildlife expert and trainer on Disney’s long-running True-Life Adventures film series.

Then in 1958, while vacationing in Alaska, he drove onto the Kenai Peninsula and knew he had discovered his new home. Two years later, he moved his young family to Moose Pass and opened a taxidermy shop to pay the bills. Soon he was working full time as a crew foreman for the U.S. Forest Service — until 1966, when he received an unexpected phone call.

On the line was Clayton Brockel, founding director of the fledgling Kenai Peninsula Community College, who attempted to woo Shaffer into the classroom. At the time, Brockel had little to offer: No salary. No campus. All KPCC classes were taught in public school buildings, after hours. Shaffer said he was too busy.

But Brockel was persistent. He had seen a first-place still-life by Shaffer in a community art show in Soldotna, and he had prospective art students ready if only he could find an instructor. He called Shaffer again a couple days later, and this time Shaffer acquiesced.

At first, Shaffer tried being both forester and educator. During the fall of 1966, for instance, he would turn loose his crew at 5 p.m., rush home to shower, then drive his Jeep 30 miles to Seward to teach a 6:30 class. The next day, he would drive 75 miles to Kenai to teach another class at 7. When his students left, sometimes as late as 10 p.m., he’d make the long, dark drive home to get enough sleep to power him through another day as foreman.

Shaffer didn’t stick with this part-time college gig to get rich. At first, in fact, he was paid nothing for his teaching and received no compensation for his commute, which he did regardless of weather. “The whole thing was on my dime,” he said. And he never cancelled a class.

“I think the main thing is, I loved doing it, thoroughly loved teaching the things I taught,” he said. He persevered on bad roads and through storms. On rare occasions he would arrive in a school parking lot to discover that bad weather had kept all his students away. “I would be there if I had to do it on snowshoes,” he said.

By 1972, when the college had established its own campus, Shaffer had moved from Moose Pass to Soldotna and from unpaid adjunct to salaried full-time instructor, teaching art and naturalist studies classes. He established on-campus nature trails and frequently led groups of students through the woods in search of plants, birds, mammals, insects and fungi. He also developed a loyal following of art students by focusing on classic Alaska landscapes, and he tirelessly promoted the college and his naturalist philosophies throughout the community, often with live specimens in tow.

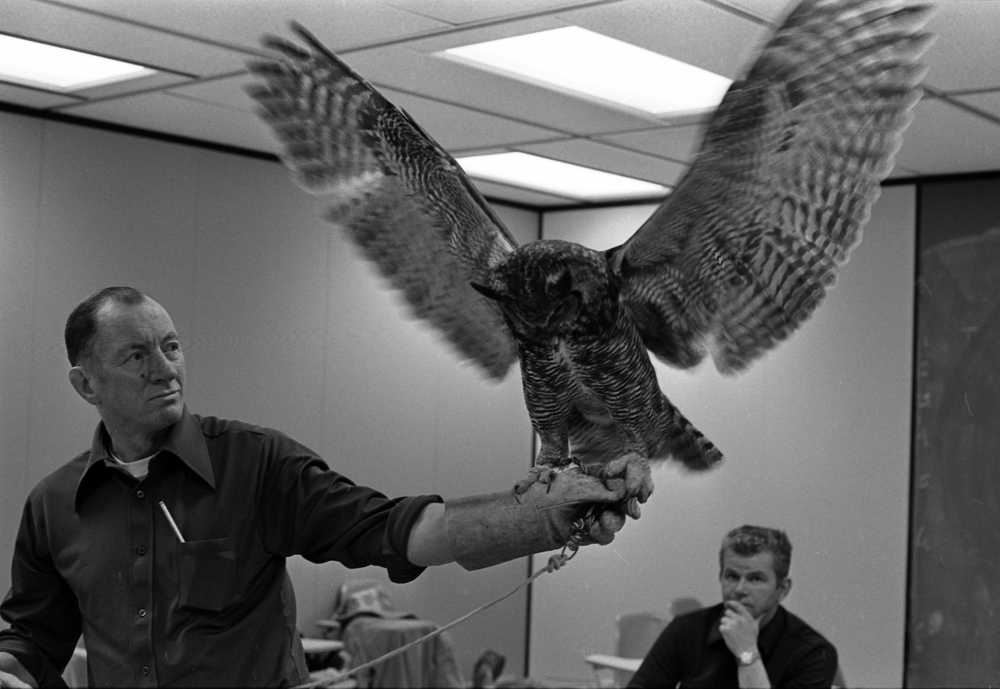

For a while, as he worked to educate the community about its environment, Shaffer toured local schools with a tamed great horned owl. In May 1975, a newspaper article featured Shaffer with his owl. “I have found that if people have a positive experience with something when they are young,” Shaffer said in the article, “they develop a much different attitude about these [things] when they encounter them later in life.”

Shaffer founded the Alaska Mycological Society and the Kenai Peninsula Botanical Society. His volume on local plant life, The Flora of Southcentral Alaska, was published in 2000.

“Boyd Shaffer absolutely loved to teach, preferably outside,” said Alan Boraas, a KPC anthropology professor who taught with Shaffer for 30 years and is now the college’s longest-tenured instructor. “He wasn’t much into new techniques of pedagogy. He was old school—he lectured and demonstrated and students listened, took notes and asked questions. He wanted to understand as much as he could of the natural history of the Kenai Peninsula and wanted to teach what he learned. His art was an extension of his natural observations.”

Boraas also recalled Shaffer’s disdain for administrative meetings, which Shaffer himself once described as an excuse to “have coffee and donuts and sit in a circle.”

“As far as he was concerned,” Boraas said, “[meetings] were a waste of time when he could be doing something productive. He was his own man doing things his own way.”

Shaffer and his wife, Susan, moved to Belize after Boyd’s retirement, and there Boyd performed research on tropical plants, birds and insects and taught volunteer art classes for local residents. As his health began to decline, they moved to Seattle in 2007 to be closer to family.

“I teach because I thoroughly enjoy teaching,” Shaffer said in 1985. “If I retired tomorrow, I think I’d see if I could get a job teaching at the college.”