Arsenio “Pastor” Credo was born in Juneau and he wants to die there, too.

As an Alaska Native, he was entitled to up to 160 acres of land in Alaska via the 1906 Alaska Native Allotment Act. But, Credo never got the chance to apply for his rightful land because he was off fighting in the Vietnam War, which was precluded following the passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act in 1971.

However, just this past August — more than 50 years later — the U.S. Bureau of Land Management announced an order and made available more than 27 million acres of public land to Alaska Native veterans who were unable to apply for their acres of in-state land due to serving during the Vietnam War between 1964 and 1971. The announcement following a lengthy review after the passage of 2019 Dingell Act.

Of the more than 1,800 veterans across the state who are eligible to receive land, around 500 are from Southeast Alaska, according to Darrell Brown, veterans land specialist for Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska.

For Credo — and for many veterans living in Southeast Alaska, there’s only one problem — Southeast Alaska land is nearly entirely excluded from the program.

“It’s for us, but it’s not Southeast — it’s all up north,” he said. “It’s not right — they know we live down here and were born here.”

The parcels are mostly in the Kobuk-Seward Peninsula, Ring of Fire, Bering Sea, Western Interior, and East Alaska planning areas, with a very small number of lots in Southeast Alaska north of Skagway and Haines.

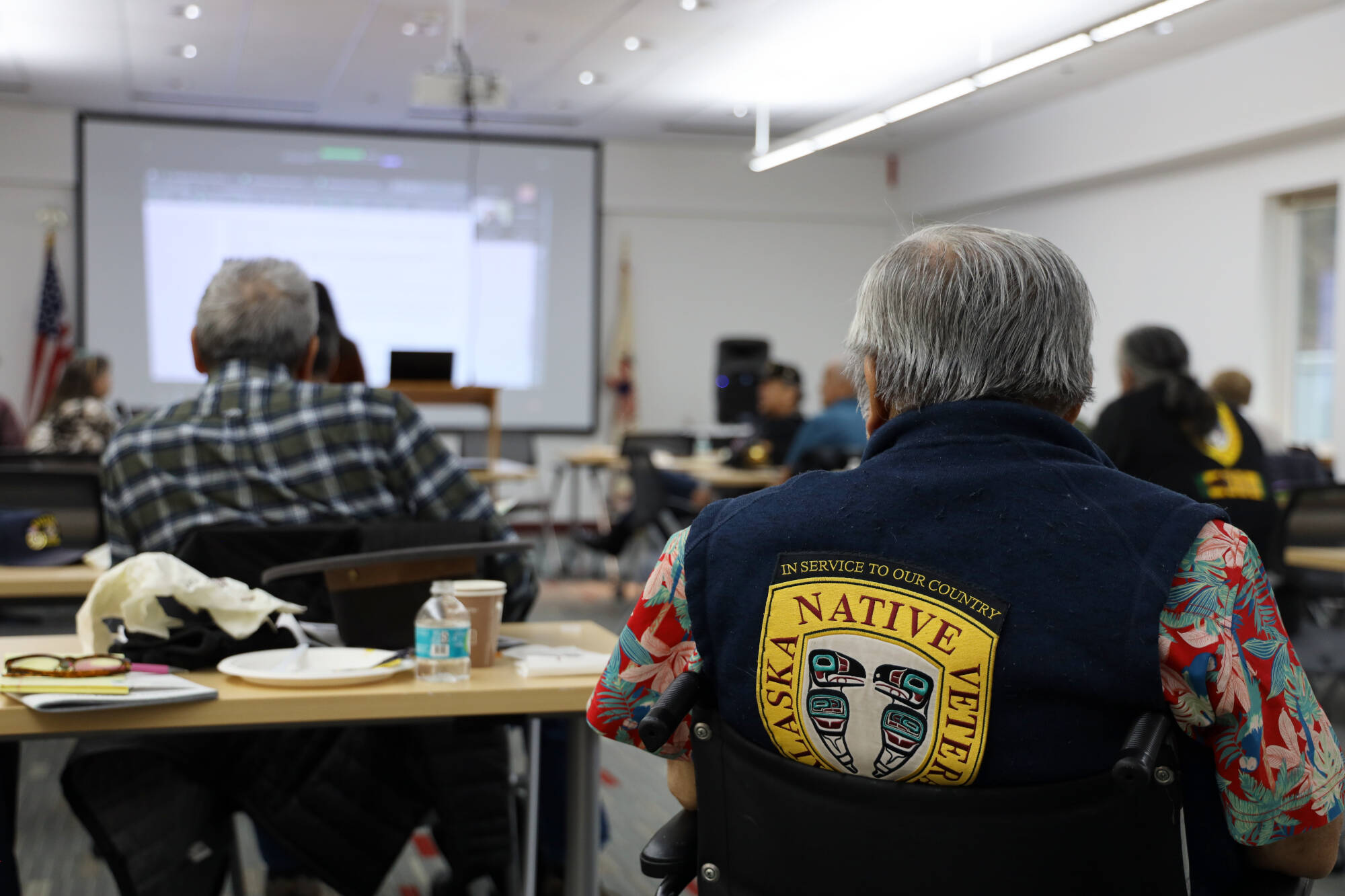

On Thursday, veterans living in Juneau or Southeast Alaska were invited to an event that offered them more information on how to apply for and receive the available land. The event was co-hosted by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska.

Candy Grimes, the bureau’s Native Allotment coordinator, said she and other representatives came down from Anchorage intending to help as many Native veterans as possible get the resources they need to apply for the lands.

“Our goal is to have 100% applications,” she said.

However, among the 45 or so veterans who showed up for the event, there was general unhappiness about the lack of Southeast Alaska land.

“They would rather have landed in their homelands,” Grimes said.

Southeast Alaska Native veteran Cmdr. Wm. Ozzie Sheakley who attended the event agreed.

“It’s too far away, there’s nothing in Southeast Alaska — we want Southeast Alaska,” he said.

Sheakley said he’s been waiting for this land ever since returning from Vietnam. For the past 20 years, he was a part of the efforts to push for the order and include large portions of land in Southeast Alaska. As seen in the map of available land, getting Alaska Native veterans land was successful, but including Southeast parcels was not, and in order to now add Southeast Alaska land, it would require an amendment of the order.

Sheakley and Credo said they don’t know if they’ll be around by then.

“I’m going to do it because it’s all there is,” Credo said. “I can’t wait — an amendment could take 20, 30 years and by then most of us will be dead.”

According to Jessie Archibald, senior staff attorney for Alaska Legal Services, legal representatives can apply for the land on behalf of already deceased veterans who were eligible for the lands, which is estimated to be 40% of veterans.

Eligible Legal representatives and veterans have until Dec. 29, 2025, to apply for the allotments. According to Grimes, once the application is accepted it takes around two years for the allotment to take place. So far, 253 applications have been received, and eight have been certified.

“It’s hard,” Sheakley said. He explained that despite his disappointment in the land offered, he’s still going to apply.

Sheakley said the situation reminded him of what happened to the Cherokee Nation after the Indian Removal Act, which was signed into law in 1830, forced the tribe away from their ancestral homeland and into a land unlike their own.

“It’s a bunch of land in the middle of nowhere, we don’t know anything about up north,” he said. “We want our homeland, where we come from.”

Contact reporter Clarise Larson at clarise.larson@juneauempire.com or 651-528-1807. Follow her on Twitter at @clariselarson.