The Kenai Peninsula Borough School District’s advisory committee on Native education is looking for suggestions on how to fill the various educational gaps the district’s Native students face.

Native Education Program Coordinator Conrad Woodhead and members of the school district’s Title VI Indian Education Advisory Committee led a gathering of Native leaders last Friday at the Dena’ina Wellness Center in Kenai. The goal of the meeting was to gather input from tribal leaders and partner organizations for the committee to use when prioritizing how Title VI funds should be used.

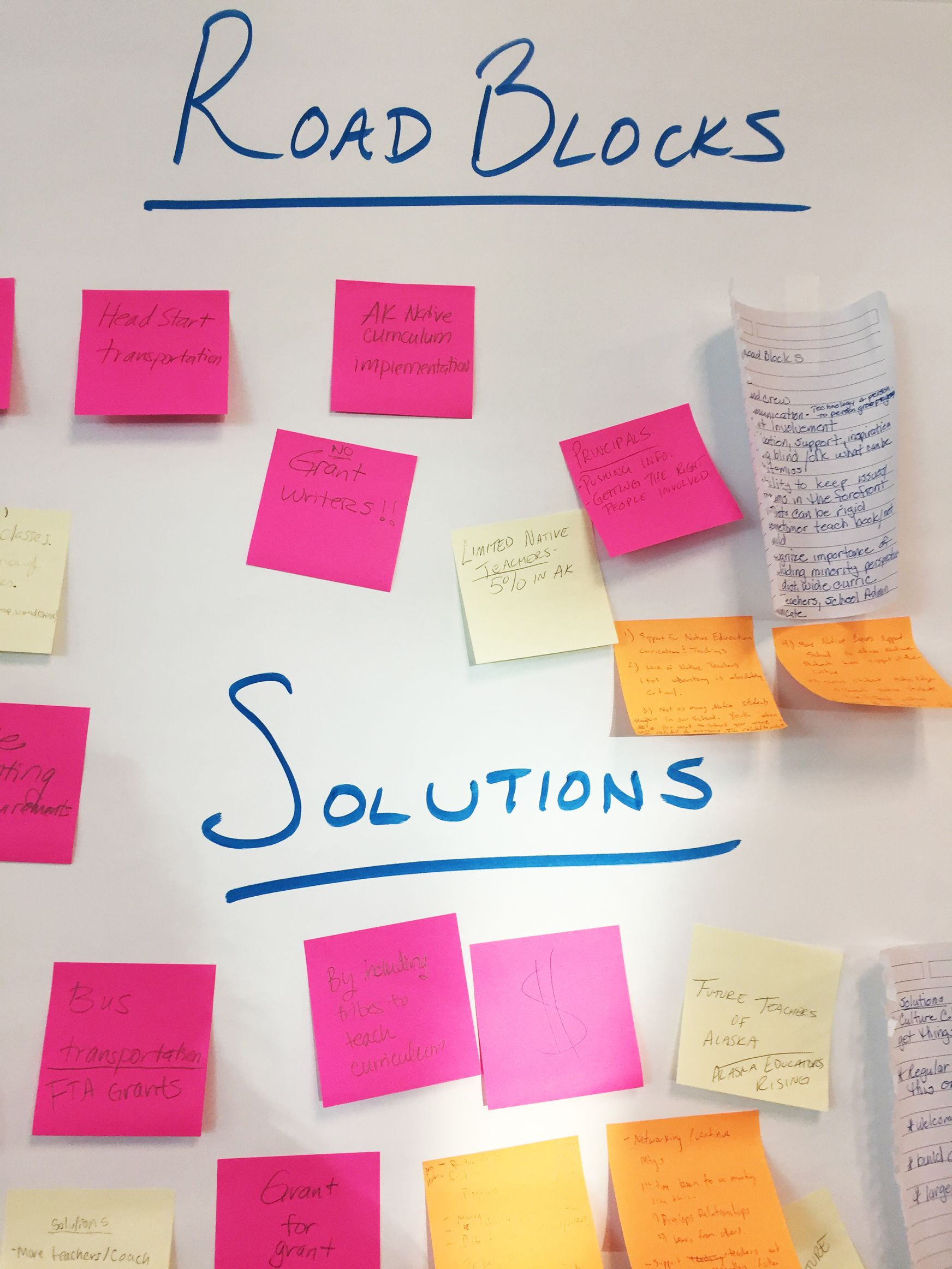

The meeting was the first of its kind to the best knowledge of the organizers, bringing together representatives from groups including the Kenatize Indian Tribe, the Ninilchik Village Tribe, Tyonek Native Corporation, Seldovia Village Tribe, Chugachmiut Native Association, Project Grad and the school district. They broke out into smaller groups to come up with what they feel are the biggest roadblocks and challenges facing Native education in the district, as well as some ideas for solutions to those challenges.

The federal Every Student Succeeds Act, the successor to the No Child Left Behind Act, renews an emphasis on getting feedback from stakeholder groups when it comes to Title VI, formerly Title VII under the No Child Left Behind Act, Woodhead said. The suggestions gathered during the meeting will be used by the advisory committee when its members prioritize what programs to fund with Title VI money, and the district will take those priorities into consideration, he said.

“I think providing that opportunity for us to share what we’re doing and why we’re doing it, and also providing our Native partners and future partners a chance to tell us what’s important to them was overdue,” Woodhead said.

The approximately 1,200 Native students identified in the district represent 114 tribal entities in Alaska, Woodhead said. This makes serving their needs and obtaining funding through grants difficult because the needs and cultural affiliations are very diverse, he said.

“When you’re the size of West Virginia and covering 43 different sites and trying to meet the academic and cultural needs of 1,200 students, it’s a challenge,” he told the gathered representatives. “And that’s why it’s important for us to be on the same page and pursue things together.”

The district currently gets $476,000 for its Title VI programming, Woodhead said. Those funds are largely focused on sending middle school students to the Alaska Native Science and Engineering Program, working with partner Project Grad to identify and support Kenai Peninsula Native Youth Leaders at district schools and placing tutors in schools for Native students.

Since Woodhead began his half-time position coordinating Native education programming in addition to being the principal of Chapman School in Anchor Point, he said the number of identified Native students in the district has grown by more than 100. The district’s current graduation rate for its Native students is 80.43 percent, up from 72 percent the year before, he said.

Still, he and the participants emphasized several gaps in Native education, like the level of parent involvement, bullying, lack of access to technology for some schools and lack of reliable transportation for students to attend camps, cultural activities and more.

“We need to do better,” said Superintendent Sean Dusek at the start of the meeting. “And our district is fully committed to serving all of our students the best that we can. One thing that public education does struggle with, though, is to be all things to everyone, and we just don’t have the resources for that.”

Dusek said he’d like at least one action step to come out of the gathering for the district to move forward and work on.

“I look forward to taking what we come up with today, but having all students participate, not just Native Alaskans,” Dusek said. “All students, because all of our students can benefit with cultural relevance.”

Getting cultural experiences integrated into education in the district was brought up several times by Friday’s participants, both as a challenge or road block and as a suggestion or solution. It was suggested that students be given school credit for cultural experiences, camps or excursions to encourage them to participate.

Other challenges brought up at the meeting were issues with substance abuse, maintaining enrollment for Native students, trouble with finding grant writers who understand the district’s extreme cultural diversity, a lack of Native teachers, lack of access for parents to early learning programs and after school programs, and school start times, which some said are too early to be conducive to optimal learning.

The district has also put out a needs assessment survey so that parents and students can weigh in on these kinds of issues as well. So far, 63 people have filled out the survey, Woodhead said.

When it came to possible solutions the school district could use to improve its Native education programs, the meeting participants suggested encouraging parent involvement, building a list of district assets, forming more partnerships between tirbal entities and schools, recruiting more Native teachers, including a section on culture during teacher training, and better addressing racism and bullying.

Several organization and tribal representatives suggested holding a follow up meeting similar to Friday’s to make sure the work doesn’t stop at the ideas generated at the meeting.

The next steps are for Woodhead to synthesize the feedback gathered during the meeting and send it out to participants and partners. Then, he said, the advisory committee will use that feedback as well as results from the needs assessment survey to help form funding priorities.

“What’s important to me is trying to provide a level of equitability from one end of the district to the other because we have a very diverse Title VI population,” Woodhead said.

Reach Megan Pacer at megan.pacer@peninsulaclarion.com.