A group of scientists is coming together to share information related to harmful algal blooms in Alaska.

Under the umbrella of the Alaska Ocean Observation System, part of the national ocean observation system network, a partnership of state agencies, Alaska Native organizations and the University of Alaska has launched the Alaska Harmful Algal Bloom Network. The intent is to stitch together a statewide approach to researching, monitoring, responding to and spreading information about harmful algal blooms in the state.

Algal blooms are natural processes in the ocean and occur when the population of algae in a certain area increases dramatically. However, they can turn toxic when certain types of algae proliferate and produce chemicals that can be harmful to other plants, animals and people, or consume all the oxygen in the water as they decay. The events, called harmful algal blooms, occur all over the planet, in both freshwater and the ocean, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“Over the last 10 years, we’ve been seeing more and more of these bloom events happening,” said Ginny Eckert, a professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Juneau and co-chair of the Alaska Harmful Algal Bloom Network’s executive committee. “It’s always a question: Are we seeing more because we’re paying attention more? But … the more information we can get out to people, (the better).”

Harmful algal blooms can have devastating consequences. In 2014, nearly 500,000 Ohio residents had to go without clean drinking water because of harmful algal blooms near a water treatment plant in Lake Erie. A harmful algal bloom in a lake that flowed into the ocean near Monterey Bay, California in 2007 is thought to have killed 11 sea otters with infections of microcystin, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Every year in Alaska, a number of alerts go out to shellfish gatherers to be careful because some of the clams, oysters and mussels may have high levels of a toxin that causes paralytic shellfish poisoning, a fatal condition in humans.

Paralytic shellfish poisoning is particularly concerning in Alaska’s rural subsistence communities, where there is less information available and people are more dependent on gathering wild foods. Tests are costly and not easy to get, and cooking the shellfish doesn’t kill the poison. The Alaska Department of Health and Social Services’ official advice is to treat all noncommercially harvested shellfish as toxic, and if they choose to do so anyway, not to eat alone and know the symptoms of PSP.

Though PSP is one of the major pressing issues resulting from harmful algal blooms, it’s not the only one the members of the group are interested in, Eckert said.

“We’re interested in all the issues that affect humans and wildlife health, including birds and mammals,” she said. “That is a big gamut of things out there. In Alaska, PSP definitely comes up as one of the most pressing health issues, especially for people, and as the waters are warming I think there may be other issues that are coming us as well.”

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency released a white paper in May 2013 saying changing environmental conditions in fresh and marine waters could favor harmful algal blooms. Harmful algae usually boom during the warmer months or when water temperatures are warmer than usual. As waters warm earlier and later in the year, the areas susceptible to harmful algal blooms could spread. Increasing salinity and carbon dioxide levels and coastal upswelling could also increase incidences of harmful algal blooms, according to the EPA.

There didn’t used to be algal blooms in the Aleutians. Now, they’re frequent enough to lead to significant PSP issues in the area’s shellfish, said Bruce Wright, the senior scientist with the Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association, the Alaska Native tribal organization representing the Aleut people.

“In the Aleutians, 100 years ago, they didn’t have PSP out there,” he said. “In our case, in Alaska’s case, it’s just a matter of water temperatures.”

There are a number of different kinds of algae that cause harmful blooms, with different effects. The tiny microorganisms that cause PSP, a genus of dinoflagellates called Alexandrium, produce a toxin that is water soluble and doesn’t stay in a person’s system long-term. Mussels build it up quickly and are a snapshot of what’s going on now in the water, while butter clams store it up and can hang onto toxic amounts of the poison long after the bloom has ended, Eckert said. Other types of blooms cause the release of a toxin called domoic acid, which has been shown to cause permanent neurosystem damage in mammals, including humans.

In 2015, the Gulf of Alaska saw broad algal blooms, likely as a consequence of a mass of abnormally warm water nicknamed “the blob” in the North Pacific. That same year, more than 30 large whales were reported to have died in the western Gulf of Alaska, including fin and humpback whales. The National Marine Fisheries Service reported that the definitive cause was not confirmed “although ecological factors were a contributory cause,” citing the ongoing El Nino event, the blob and domoic acid from a west coast algal bloom. Wright said the researchers were not able to sample any of the whales but many attributed the mortality event to domoic acid.

The Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association is participating in the Harmful Algal Bloom Network and Wright serves on the executive committee. The association is also working with Alaska SeaGrant, he National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, on developing a field test for PSP, using a grant from the North Pacific Research Board.

“We’re all providing samples for that objective,” Wright said.

All the partner organizations are doing their own research, but it’s possible they could apply for funding as a group through the network, Eckert said. Ultimately, the goal is to be able to forecast when harmful algal blooms will happen and prevent harm to humans, she said. The advantage to a network is to help cover more distance — Alaska is a massive state with a lot of diverse coastline.

“The network is more of a coalition, it’s not really an agency,” she said. “… It’s sort of a forum to share information. It’s not really a brick and mortar kind of thing.”

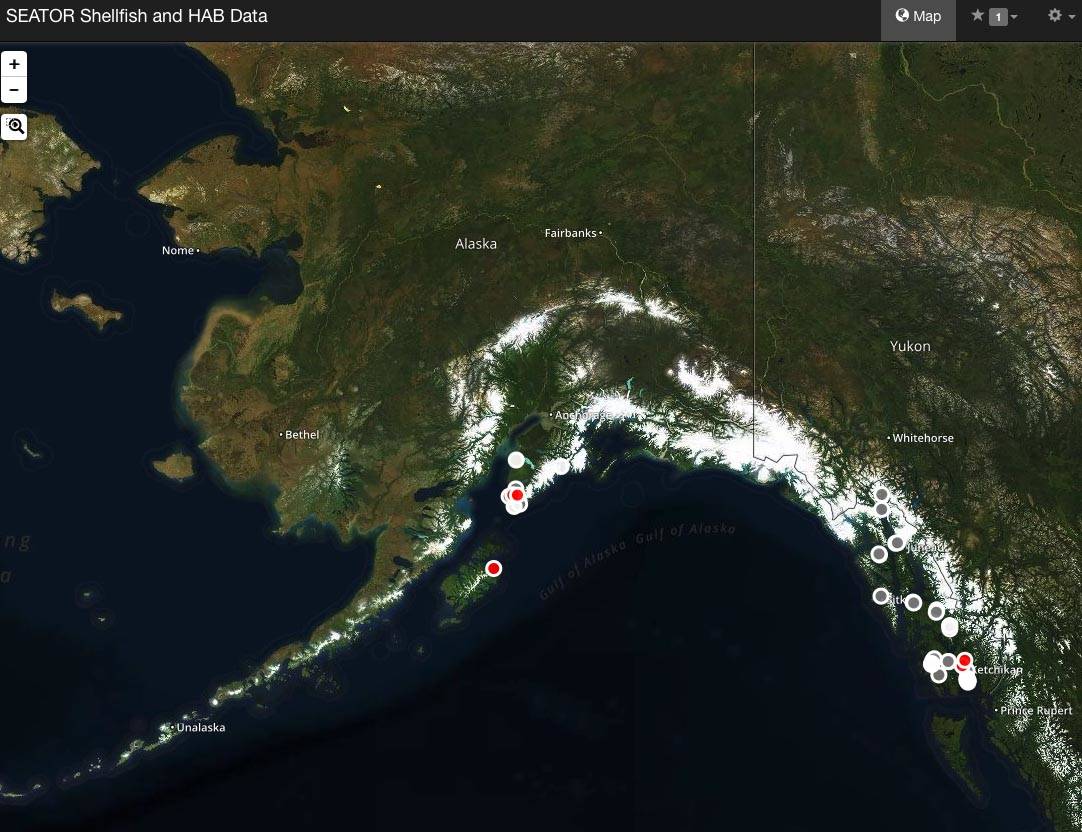

The Alaska Harmful Algal Bloom Network keeps a number of resources on its website, including a portal showing where PSP advisories have been issued.

Reach Elizabeth Earl at elizabeth.earl@peninsulaclarion.com.