On Thursday Kenai Peninsula residents met the farthest-traveling visitors to Kenai in the town’s history.

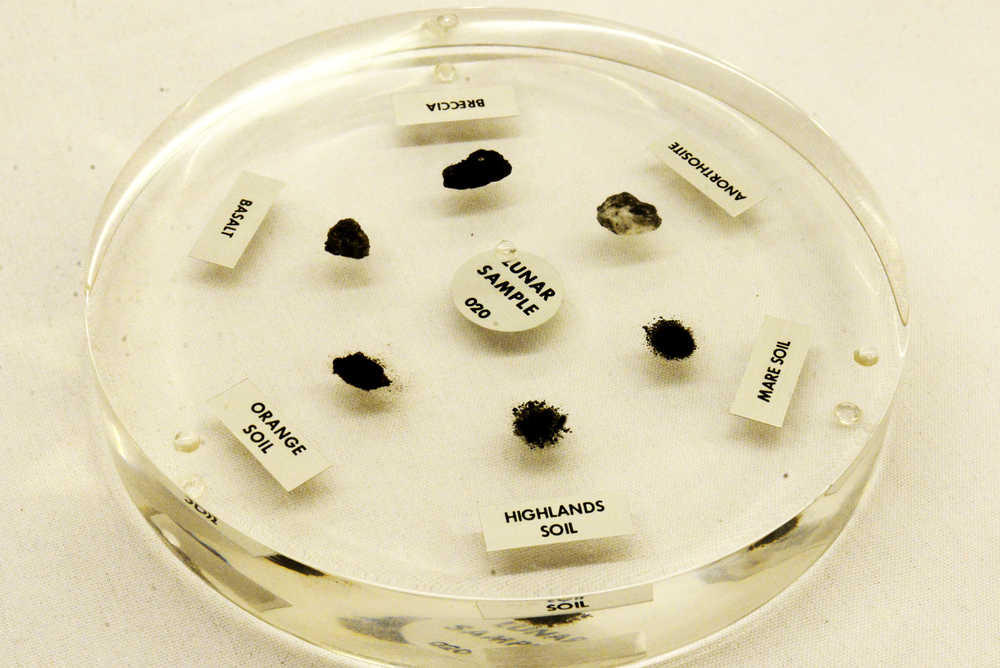

These weren’t tourists, but a set of six lunar mineral samples harvested by the Apollo 15, 16, and 17 missions in the early 1970s. Embedded in a lucite disk, they made up NASA’s lunar sample kit 20, on loan from the space agency for a one-night appearance at Kenai’s Challenger Learning Center.

“This is by far the most people we’ve ever had for a Challenger event,” said Challenger’s Education Director Summer Lazenby. She said that when she planned the event in August 2015, and applied for the loan from the Johnson Space Center’s Astromaterials Acquisition and Curation Office, she had expected around 150 to come.

Instead, Challenger staff later estimated that around 450 people stood in line to file through the room where Lazenby kept close watch over the moon rocks.

Some were first drawn to the two gray rocks sitting on the table nearby, believing them to be lunar. Actually they were samples of terrestrial basalt, a mineral common on both the earth and moon, provided because they may be similar in look and feel to the moon rocks. The actual moon rocks could be examined through the disk, but not touched.

The six samples consisted of three soil samples — one each from the high and low-lying regions of the moon, and one that had partially oxidized on contact with Earth’s atmosphere, turning orange — and three rocks — a breccia composed of fused fragments of meteor-shattered rocks, and lava-formed basalt and anorthocite. A shiny white circle was visible on the side of the anorthocite pebble. At some point in its lunar life, it had been struck by a dust-sized micrometeorite that had fused its material into a tiny glass crater.

A second lucite disk exhibited alongside the moon samples contained fragments of a much larger meteorite discovered in Antarctica.

“It’s not that Antarctica attracts meteorites,” Lazenby told visitors. “It’s just easier to find them there because everything else is white.” She spent two hours speaking to the stream of visitors, answering their questions and quizzing them about the Apollo missions, asking how many manned moon landings there had been (6), how many people had walked on the moon (12 men and zero women), and when the last one occurred (1972). Between them, the Apollo missions returned 842 pounds of lunar material, some of which NASA loans out for educational displays.

Other rooms of the Challenger Center hosted activities ranging from a planetarium show inside an inflated dome to a demonstrations of core sampling using blueberry muffins and drinking straws. In the Challenger Center’s two space simulation rooms, a crowd was playing through the center’s new simulated space mission, Lunar Quest, in which two teams of science students — one playing mission controllers and the other playing lunar colonists — work on computers, cameras, and remote-controlled robot arms to perform simulated tasks such as collecting and analyzing spectrography data from a lunar impactor probe and dealing with an outbreak of bronchitis aboard a lunar colony.

Lunar Quest is the newest of 25 mission simulations that the Challenger Center will run for local science classes. Like other missions, it was sponsored by the petroleum company Tesoro Alaska. Unlike the others, Lazenby said it makes use of real-time data.

“The Lunar Quest mission is a game-changer for the Challenger Network,” Lazenby said. “It’s a major step forward as far as technology goes. … With the Lunar Quest mission, they actually do real-time lunar. So we’re traveling to the moon, and they put in today’s date. They’re dealing with the numbers that it would take today if they actually wanted to go to the moon, wherever the moon is in relation to the Earth. They actually use those numbers to calculate how much thrust they need, and how long they need to burn their engines to get to the moon.”

The mission will have its first real run on Monday and Tuesday with students from Tustumena Elementary.

In spite of the busy activity in the mission simulation rooms, Lazenby said the night’s big draw was the adventurous connotations of the lunar samples.

“The trip to the moon, that was the space race,” Lazenby said. “We said ‘we will go to the moon,’ and we did. And the availability to get to bring these here and allow residents of Alaska to see them, these are really unique. … It’s a really unique thing. Bring the moon rocks in and let the kids experience some unique science and we debuted our Lunar Quest mission. How can you beat moon rocks?”

Lazenby said her training to handle them consisted primarily of security procedures.

“We haven’t been to the moon since 1972, and there’s a finite amount of these,” Lazenby said. “They’re very hard to replace.”

Following the exhibit, the moon rocks were stored in a safe in the Kenai Police Department headquarters before being shipped back to NASA.