They couldn’t have timed it better.

As the last of the interagency team of invasive northern pike killers stepped off of the Derks Lake on Thursday, it began to snow in Soldotna. If all goes according to plan the fish killing piscicide rotenone will work its way through each of the four lakes treated by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, its degradation slowed by the coming winter. When it breaks down completely, it will leave behind pristine, but empty, waters to be restocked with native fish in the coming years.

The state agency moved quickly after getting the final approval for the extensive project which, when completed, will be the eighth and largest pike killing project to-date in the state. It will take four years and more than $1 million in both state and grant funding, but if the plan succeeds, the Soldotna Creek Drainage should be free of northern pike by 2018.

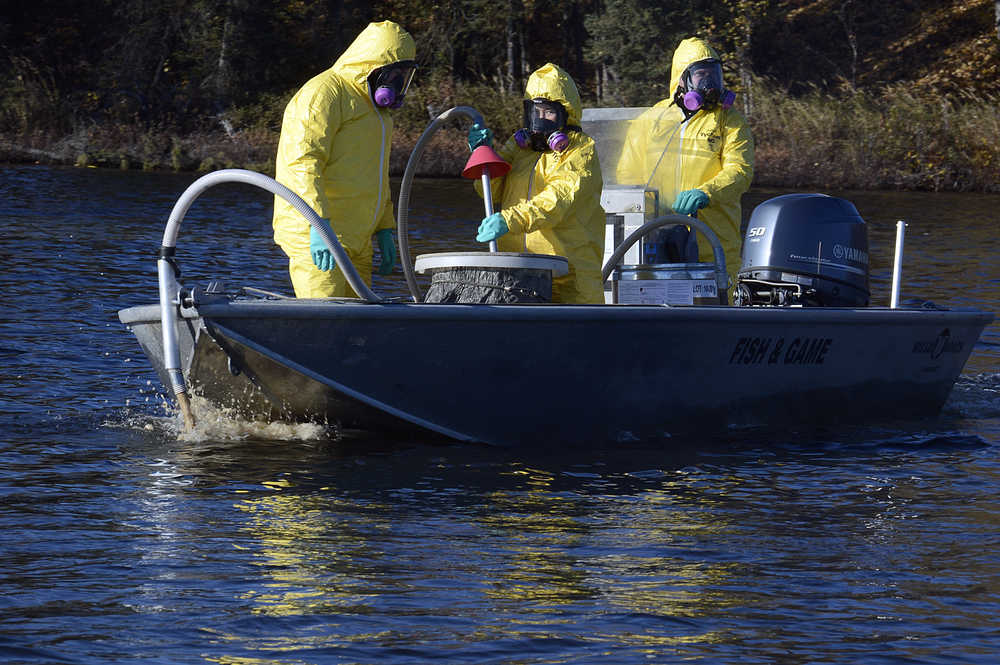

As dozens of personnel in bright yellow hazardous materials suits crossed East Mackey lake on Wednesday, Area Management Biologist Robert Begich and Assistant Area Management Biologist Jason Pawluk sat in a boat netting dead pike that floated to the surface.

“We’ve not picked up any other kind of fish,” Begich said.

The rotenone is being applied in two forms, powder and liquid. Both compounds have to be mixed with the lake water, as the chemical is not very water soluble, before they’re applied. Several boats on the lake apply the poison and then run through the surrounding waters to help mix the poison deeper into the water column.

As the rotenone spread through the lake, the occasional white-bellied fish floated to the surface, its body no longer able to process oxygen.

The poison, rotenone, penetrates the fish’s body at a cellular level and makes it impossible for the fish to use oxygen it takes in, according to the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

It isn’t just fish that are affected by the rotenone however, it’s any invertebrate. Invertebrates are animals that lack any internal or external bone skeleton. They vast majority of animal species on the planet are invertebrates and some of them, like insects, fall squarely into the category of fish food.

“Invertebrates are one of the groups that’s hardest hit, particularly plankton,” said Fish and Game biologist Krissy Dunker, during a recent presentation to the Alaska Board of Fisheries. “Their populations can take between one and two years to fully recover.”

Fish and Game researchers spent time studying the affects of the poison on invertebrate populations as part of the permitting process for the project.

“We needed to ensure that there’s food and forage available for the fish that we’re putting back in (to the water),” Dunker told the board.

Some results were encouraging, she said.

“We did see, at Scout Lake, one year following the treatment … we immediately that spring found tadpoles swimming in Scout Lake and it looked like the loons were feeding on them. We weren’t sure how that was going to play out, but we were encouraged by that.”

Pawluk and Begich zipped around the lake in an aluminum boat, netting the fish as fast as they appeared in an effort to keep the smell of rotting fish to a minimum. There are large houses dotting the shorelines of three of the four lakes Fish and Game treated this year.

“We told people we would do that,” Begich said.

In addition to removing dead fish from the water, Fish and Game will also be monitoring the drinking water near Soldotna Creek, though Dunker said the poison penetrates the soil to about 1 inch and isn’t a concern for nearby wells.

“The primary health concern is actually to the people who are applying the rotenone,” Dunker said.

In addition to applying the poison to East and West Mackey Lakes, Derks Lake and Union Lake this year, Fish and Game staff will monitor the degradation of the poison and continue netting underneath the winter ice, though no fish other than the northern pike are believed to be present in the lakes anymore.

After biologists are sure the lakes are free of rotenone and invasive fish, they’ll move onto the next phase of the project, which is to begin rounding up native fish from the mainstem of Soldotna Creek, Tree Lake and Savena Lake. As researchers catch the Dolly Varden, steelhead, rainbow trout, lamprey, round white fish, salmon, stickleback and slimy sculpin still left in the Soldotna Creek drainage, they’ll transfer the fish into the four lakes being treated this year.

“This will begin the process of restoring fish populations to the drainage,” said Fish and Game Regional Supervisor Tom Vania during a recent presentation to the Alaska Board of Fisheries.

Then, in 2017, Fish and Game plans to treat the majority of Soldotna Creek and the two remaining lakes known to contain northern pike.

“Some native fish will be killed in this section,” Vania said.

Once the final treatment of rotenone has been applied, Fish and Game plans to breach a barrier between Derks Lake and the rest of the Soldotna Creek drainage, allowing the transplanted native fish back into the mainstem of Soldotna Creek and, eventually restoring the native fish populations of the entire drainage.

Reach Rashah McChesney at rashah.mcchesney@peninsulaclarion.com.