When most hikers reach a summit, they look out over the landscape before them to capture that point in time. They pull out their camera or phone to get the best shots from their new vantage point. When I’ve been hiking recently, I look up into the trees to try to gauge what it looks like from the sky. I’m using an iPad, taking four pictures in the cardinal directions. It makes sense that my perspective is different because instead of looking for good views I’m helping remake a landcover map of the Kenai Peninsula.

Since July, the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge has been sending teams of biologists into the field to gather vegetation data at specific points. My partner and I started out at the end of the Swan Lake Road, with another team working from the Swanson River Road. We have since surveyed all roadside points in between, plus others in the Swanson River Oil and Gas Field, and along Skilak Lake Road.

Not all the points, however, are accessible from a road. Some are closer to lakes and rivers, so we use a boat to access those plots along the shores of Tustumena Lake and Skilak Lake. For several days, two teams of two or three people leapfrogged each other around the lakes, surveying one point as the other team was dropped off to survey the next point.

From the spot where we jump off the boat or park the truck, we use a compass and GPS to navigate to our sampling points. These points can be as close as 200 feet away to almost a mile away, longer still if there is more than one point in that area. When it’s more efficient to go from the first point directly to the second point, instead of returning to the vehicle, we sometimes hike over a mile to complete a series of points. But, of course, that means hiking through whatever terrain is between us and the next point.

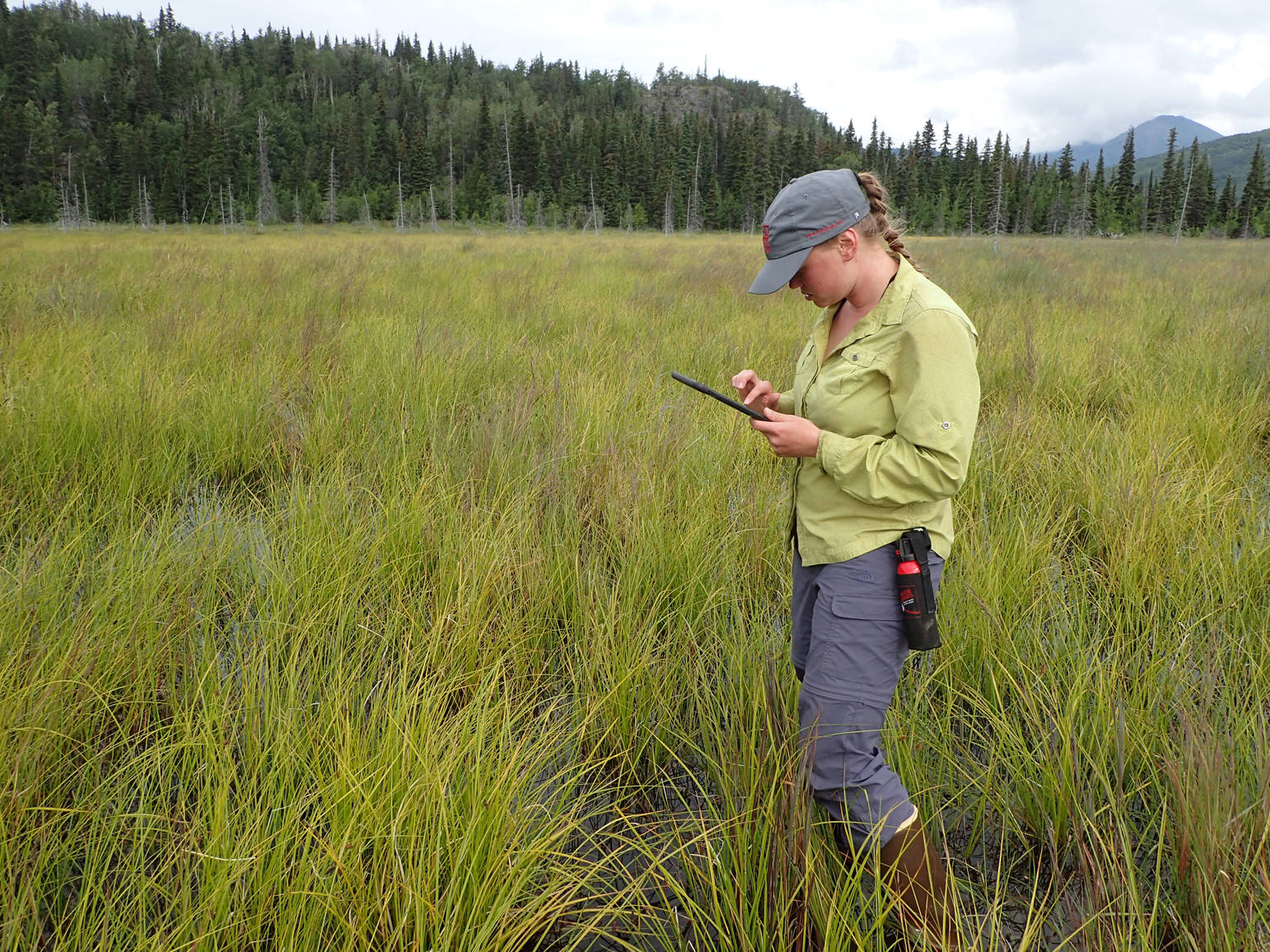

Sometimes it’s easy, walking through groves of “quakies” and birch trees. Other times it’s more of a challenge, scrambling over fallen or burned logs, pushing through devil’s club, crawling under elderberry thickets, slogging through peatlands (which seems to be a favorite of whoever set the points) or scaling a rock face.

We begin flagging when we get to the point in order to delineate 50 feet, the radius of the circular plot we’re surveying. One person walks the perimeter if it’s difficult to see to make sure all the plants are included. After determining the slope and aspect of the plot, we estimate the percentage of the different species of trees, shrubs, forbs, grasses, ferns, mosses, lichens and deadfall within the 50 foot radius as would be seen from above by an eagle or, in this case, by high-resolution digital photography captured from a fixed-wing aircraft. The data are entered into Survey123, an app specifically designed for these surveys.

At the end of the day, all of the points that were surveyed are submitted to the Forest Service’s Remote Sensing Application Center where they are compiled onto a digital map so the field teams can track what areas have been completed in real time.

Back in 2006, Lee O’Brien, a GIS expert with the Kenai Refuge, made a landcover map of the Kenai Peninsula. Since then, vegetation on the Kenai Peninsula has undergone dramatic changes from a rapidly warming climate, as well as from wildfires and spruce bark beetle attacks. This summer, biologists at the Kenai Refuge, along with their counterparts from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game and Chugach National Forest are joining forces to resurvey the Peninsula. The difference between then and now, a span of a bit more than a decade, is that this mapping effort is using high-resolution digital photography rather than satellite imagery.

Eventually, the analysis of the imagery, called a supervised classification, will be completed by software with unusual names such as RandomForest and eCognition. Before the supervised classification can model the data and create the map, however, there are about 1,600 points that need to be surveyed. The more accessible half of those data points will be obtained by foot and other, more remote plots by observation from a hovering helicopter.

The importance of having an accurate, up-to-date landcover map of the Kenai Peninsula can’t be overrated. It is a cornerstone for modeling wildlife habitats, assessing fire fuel loads, and evaluating land management by all agencies.

Mary Thomas is an undergraduate in Animal Science at Colorado State University who is doing a biological internship at Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. Find more information about the Refuge athttp://www.fws.gov/refuge/kenai/ orhttp://www.facebook.com/kenainationalwildliferefuge.