HOMER — What’s the difference between a sensor and a censor? Does it mean anything if a stamp is upside down? What is the significance of June 1944? These were just some of the hard-hitting questions fifth graders at West Homer Elementary tackled as mini detectives in a special lesson.

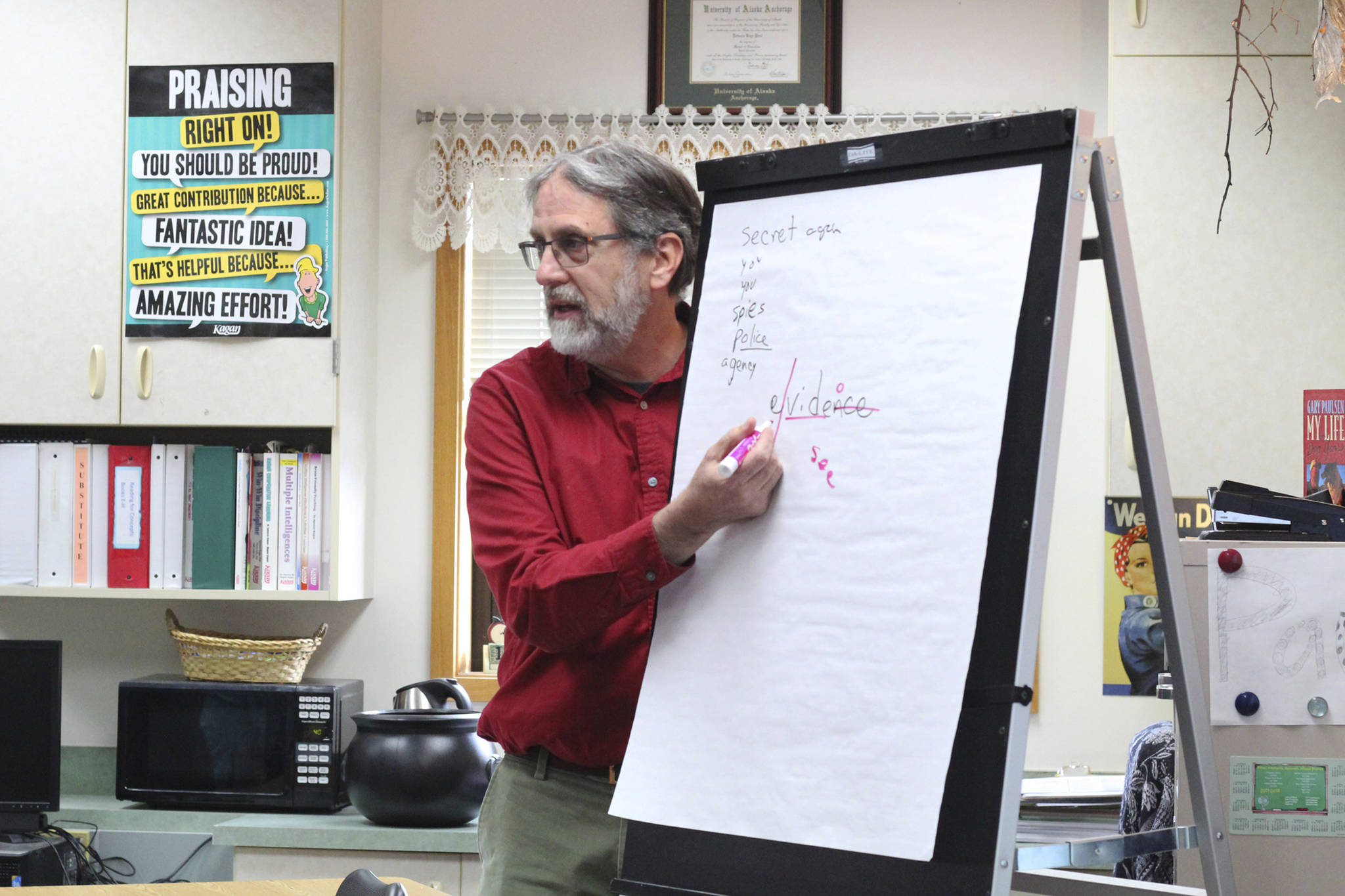

Former McNeil Canyon Elementary School educator Bill Noomah visited Becky Paul’s class on Oct. 19 to turn each and every student into a pro investigator. Arming them at first with only a photo of an old letter from a member of the U.S. Navy and their own observation skills, Noomah took them on a journey of war, historical social norms, battle and recovery in a lesson he created using a collection of interviews, documents and art from the Veterans History Project.

Noomah created the lesson about 10 years ago during a teacher training event in which the participating educators were being taught how to utilize the Library of Congress’s then-newly digitized collections as primary sources. Each teacher was asked to create a lesson they would be willing to teach in their classes based on materials from any of the collections. Noomah was browsing through the library when he was hooked by a collection from the Veterans History Project, he said.

“The work of T. A. Sugarman . just jumped out at me,” he said.

Sugarman was an ensign in the Navy during World War II and provided the Veterans History Project with an extensive collection. Veterans History Project Director Karen Lloyd was in Alaska already and made the trip to Homer to watch Noomah put his lesson using the Library of Congress resources to work, and commended his choice.

“Tracy Sugarman is this amazing artist, and not only did he do art as a way to relieve his stress during the war, but he continued afterwards,” she said. “And so we have all this amazing art from him.”

Noomah used the lesson to teach his students about Veterans Day, as well as to help them learn how to use primary sources for research, something he said he hadn’t done with elementary students before. His original lesson was videotaped and put on the internet, and he said he wasn’t sure what more would come of it.

About four years ago, however, Noomah found out the Library of Congress had become aware of his lesson, and he was invited by the library to speak on a national webinar panel of educators.

“I guess it just had some life and there were people who remembered it,” Noomah said of the lesson.

Noomah just retired a few months ago, but when Paul, an old friend, ran into him at the grocery store, she convinced him to come momentarily out of retirement to teach the lesson to her fifth-grade class.

“It was very timely because we had also . had had a special presenter from Island and Oceans (Center) on Oct. 13, and he had come in and talked with the students for an hour about Attu Island and about the realities of World War II here in Alaska,” Paul said.

For nearly two hours, Noomah immersed Paul’s students in the life of Sugarman just before he went off to the battle of Omaha during the storming of the Normandy beaches at the start of the liberation of Europe from the Nazis. They studied the envelope from a letter the veteran sent his wife just days before the battle, a letter she wouldn’t have gotten until the fighting had already started — and that could have been his last letter if Sugarman had died in battle.

“It’s my favorite lesson of all time,” Noomah said. “I know that I’m entering something that’s kind of a trust relationship.”

After getting the kids hooked with the thrill of being detectives, Noomah read them the real contents of Sugarman’s love letter to his wife, and showed them the artwork he created depicting the vicious storming of the beaches. More than one student was moved to tears before Noomah let them in on the fact that Sugarman had survived and died an old man in the 2000s.

“It’s about telling one story well,” he said of the lesson. “And that’s what’s different about it, and that’s what primary resources give us the ability to do, is to hear one voice clearly.”

Paul said she was pleased with how invested her students became in the investigation and how attentive they were throughout the lesson. She said the materials and Sugarman’s story helped bring to life the story of D-Day to help the students understand it on a much deeper level.

“As a teacher, to have my class completely empowered in their learning the way he was able to do that with them is exactly what we all strive to do,” Paul said.

Part of Noomah’s goal with his lesson is to help students to better connect to what it means to be a veteran. He previously worked with homeless populations both in Portland, Oregon, and in Juneau, and said the number of homeless veterans he saw has showed him that there’s still plenty of work to be done when it comes to honoring veterans.

“There’s a special place for veterans in our civic life,” Noomah said. “We devote a lot of our time and attempts at recognizing our veterans. But as someone who worked with homeless populations, I know that we often fall very short.”

For Lloyd, who was an Army aviator for 28 years before joining the Veterans History Project, watching Noomah get the kids to connect to a veteran’s personal story was a treat.

“My hope is that they will now know they’re there, and especially those that made that connection (to the material) to . ask themselves a couple of questions. One, who’s the veteran in my life? And what story should I ask them about? Or, what are those stories that they have? And if not a veteran in their life, then, you know, what about their parents?” she said.

Lloyd was already scheduled to come to Alaska, where the Veterans History Project hosted two workshops at the Alaska Veterans Museum in Anchorage. The project provides workshops and training to people around the country to teach them the interview skills needed to collect veteran stories. Those stories can then be added to the collections at the Library of Congress.

“Our goal is to reach out to volunteers across the U.S. . to encourage them to talk to the veterans in their lives,” Lloyd said. “And we give workshops. We happened to see Bill — he was working on (using the library for) teaching primary sources, and he happened to pick, lucky for us, the Veterans History Project. And he picked one of the most amazing collections.”