On the same day Iryna Hrynchenko and her son Ivan, 18, arrived in Juneau, their hometown in Ukraine was suffering what The Guardian called “a horror show” from a Russian attack resulting in “no running water, gas or electricity and apartment blocks destroyed at random.”

But at least briefly thoughts of that were eclipsed by their welcome at Juneau International Airport on June 25 by a couple of their hosts carrying a yellow-and-blue sign and flowers. Mother and son, the first refugees from the war-torn country to find haven in Alaska’s capital city, exchanged hugs with their benefactors in the shadow of a giant glass-encased bear before taking some first photos along the wall-to-wall windows overlooking a vista of nearby snowcapped mountains.

Ivan’s first impressions were pretty much the same as any first-time visitor.

“I can’t believe there’s so many … I’ve never seen so many … it’s just so beautiful,” he said.

Stepping outside for the first time through the airport’s sliding doors for his verdict was more succinct: “Wow.”

Iryna, nearby with one of her hosts, mimicked plenty of other locals enduring the weekend heat wave with a universal hand gesture for “hot.”

“She’s never seen anything like this on this scale,” Ivan said of her first impressions, translating for his mother. “She loves it because of the mountains.”

Iryna and Ivan’s arrival on Saturday marked the end of a four-month journey through their country, at refugee stops in Poland and Germany after crossing the border, and via flights from Berlin to Anchorage and then Juneau. Much of it was on foot and across dangerous territory, and the single suitcase they each arrived with mostly contained clothing and other items obtained from hosts when they finally reached Berlin.

It also marks the beginning of a new journey here that may last up to two years.

For Ivan, the first immediate worry in his new Alaska hometown was the last of his high school exams, focusing on specialized trade courses in computer engineering scheduled to take place online last Sunday at 11 p.m. Alaska time (9 a.m. Monday in Ukraine). But while he expected to spend most of his first 24 or so hours here studying, he expressed optimism about his chances (and two days later felt confident he’d passed).

But first Joyanne Bloom — who led local efforts to bring Iryna and Ivan here, and is sharing her house with them during the first week of their stay — planned to take them for a walk on Perseverance Trail near her house before feeding them a welcoming meal of smoked salmon, roast beef and rhubarb crisp.

“They‘ve been eating sandwiches for four months,” said Masha Skuratovskaya, a Ukrainian living in Juneau who has family members in a village under heavy attack, who is helping Iryna and Ivan with translations as they try to assimilate into a new community.

For Bloom it’s the fulfillment, but perhaps not completion, of efforts that started by her and four other Sponsor Circles members to bring refugees from Afghanistan to Juneau. When complications with that arose her group started focusing on Ukrainians after Russia’s invasion began in February.

“We did some fundraising and background checks … but it turns out the refugees from Afghanistan chose to go where mosques and maybe Afghan communities existed,” she said. “When this war broke out we said ‘maybe we can take Ukrainians.’”

Sponsor Circles, a nationwide effort to resettle Afghan and Ukrainian refugees that claims to have more than 2,000 local groups, asks hosts to find initial housing, groceries and other essential supplies, youth education opportunities, adult employment and income support.

The match between Bloom’s group and the Hrynchenkos was coordinated by the Ukraine Relief Program, operating under the parish of the New Chance Church in Anchorage. So far the program has resettled about 200 refugees in towns from Ketchikan to North Pole (with some possibly heading for Utqiaġvik), said Director Zori Opanasevych.

“We can’t keep up with the flow of people wanting to come here,” she said.

Opanasevych said her program began sending aid to Ukraine when the war started. They were subsequently able to find sponsors in Alaska willing to host refugees, many of whom had family members or knew other people in Ukraine.

Word-of-mouth resulted in several hundred requests from those seeking to leave the war-torn country, despite the numerous climate and other unique aspects compared to most of the rest of the U.S.

“They know Alaska isn’t for everybody,” Opanasevych said. But “at this point I haven’t had anyone decline because they are desperate to be in the United States and live safely.”

Ivan, when asked what he knew about Alaska when he and his mother sought to live here, said, “I know there is beautiful nature.” But beyond that they simply wanted to escape the everyday danger of the invasion.

“We didn’t have many options,” he said.

News of the renewed attack on their Ukrainian hometown when the arrived in Juneau got an exchange of words between mother and son that was both animated and resigned.

“It‘s very sad, of course,” Ivan said. “Every day they‘re bombing our town.”

They still have family in Ukraine who were unable to flee, due to legal or practical hardship reasons.

“They can’t pass the border because they are military age, or our grandparents, for example,” said Ivan, who was able to depart despite his age due to a medical exemption.

The mother and son spent weeks crossing Ukraine, stopping in various places for short periods along the way, before taking a train to the Polish border.

“Then we just passed the border by walking,” Ivan said.

From there they walked to where they could catch a bus to a shelter for Ukrainians, eventually ending up in Berlin.

“We stayed there for a week,” Ivan said. “Some people helped us.”

They were matched up with Bloom’s group because “a friend of a friend told them about us,” Opanasevych said.

“(Iryna and Ivan) don’t have any family or anybody here, so they didn’t have any preference,” Opanasevych said. “Just the timing of them, both calling at the same time and same day I said ’perfect, let me introduce you.”

“With various people you try to make sure it’s a good fit,” she said. “It can be anything from religion, to language to whatever.”

As for the hosts, “I have a very thorough conversation with them before taking on a sponsorship,” Opanasevych said.

Bloom said she’s now well-familiar with the requirements her group — and herself personally — must fulfill, as well as the limits Iryna and Ivan will face at least initially. For instance, Bloom said while $12,000 in donations have been raised, enough to seek support for up to five refugees, the sponsor arrangement decrees that “I can show I can personally provide for these people for up to two years.”

Housing has been arranged for Iryna and Ivan until Aug. 18, after which a low-cost longer-term location is needed, Bloom said.

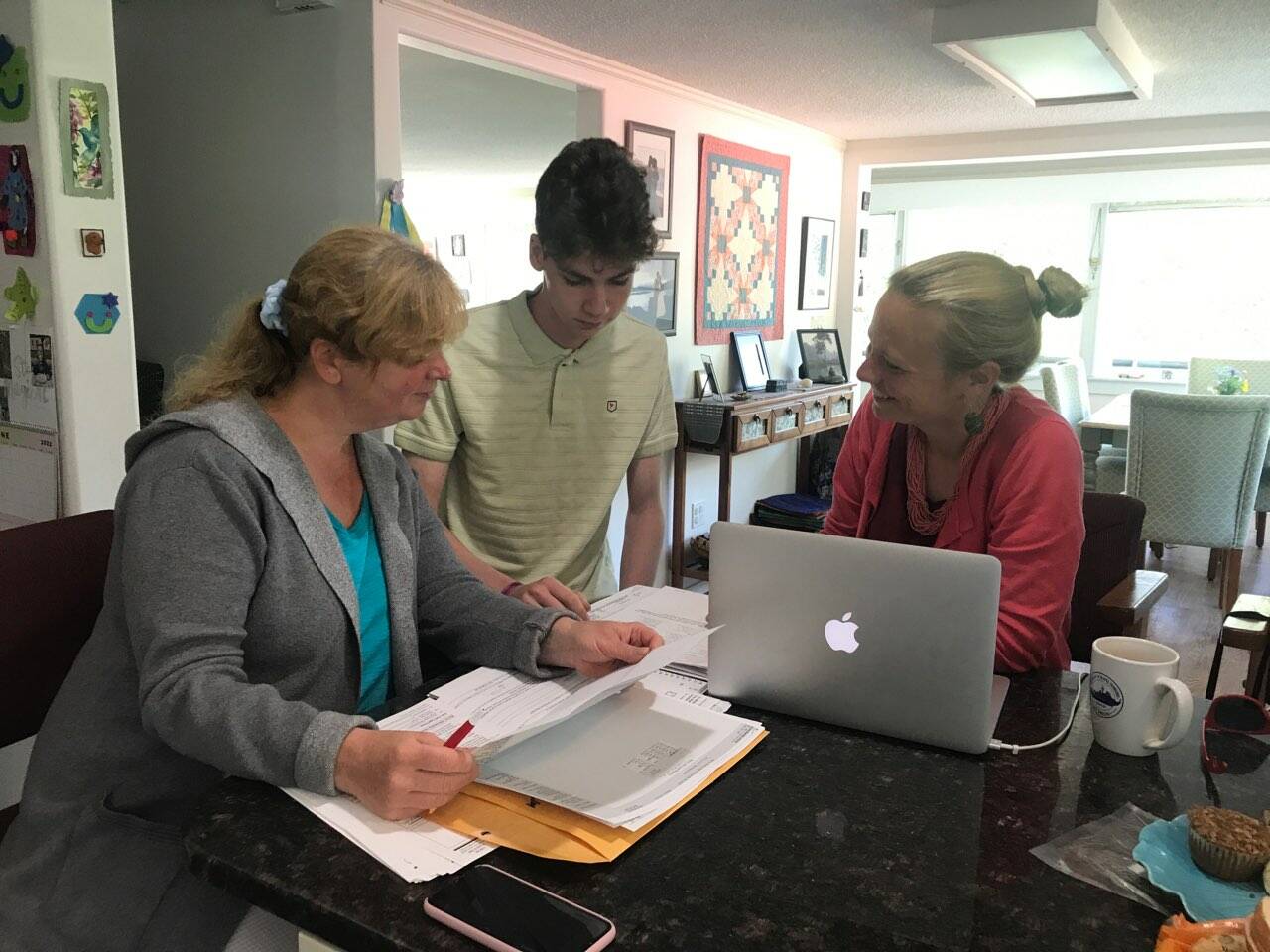

Meanwhile, Bloom spent part of Sunday taking her guests out the road and then — later than planned due to Ivan’s multi-hour exam that night — to The Learning Connection on Monday morning so Iryna could sign up to take English classes for two hours a day. While Ivan said he hopes to continue studies as well as exploring, and Iryna would like to find employment, the rules for refugees don’t immediately allow that.

“She’s a professional pastry chef” who’s worked in multiple countries, Skuratovskaya said. “I know a half-dozen places in Juneau that needed a baker yesterday.”

Iryna is for now allowed to do volunteer or what in casual terms might be called “bake sale” work, so among other things she can impressively feed those who’ve been feeding her. But as with her son’s quick grasp of the words used to describe the area, she’s quickly picking up the common lingo of just about every local resident shopping for groceries these days.

“I can’t believe you have to pay a dollar for a potato,” she said during one of her first shopping trips, according to Skuratovskaya.

While Iryna hopes her work authorization will be approved soon, Ivan has a German company who’s expressed interest in hiring him as a programmer, Skuratovskaya said. But accepting the job would mean being separated from his mother, plus other complications such as language and housing.

For local residents wondering how they can help, there’s plenty that doesn’t involve taking the sting out of insanely high grocery prices, Skuratovskaya said.

“It would be great if CBJ [City and Borough of Juneau] could issue them an activity pass (for recreation facilities) just to help them get some of the stress out,” she said, citing an example.

Skuratovskaya, who is letting Iryna and Ivan stay at her house much of the summer while she’s away, said people with similar vacancies or other available living essentials can provide non-monetary help.

Meanwhile, Bloom’s group is continuing to raise funds and exploring options for bringing three additional refugees to Juneau. She said a second group of people as well as Ḵunéix̱ Hídi Northern Light United Church have also expressed interest in hosting refugees, and a collaborative effort may be pursued.

While those hosting and arriving generally hope stays will be short, despite what joy there is finding safe havens, it appears the war is going to make such connections a long-term need, Opanasevych said.

“I wanted it to be a few weeks or a few months thing,” she said. “Now we’re looking at how to do this long-term. We don’t want this to continue, but we see that we have to. Even if war ends today we have to help them resettle for months.”

Reach reporter Mark Sabbatini at mark.sabbatini@juneauempire.com.