As the prevalence of COVID-19 in Alaska communities continues to climb, health experts explained how an ongoing backlog of case data is affecting the way new cases are reported each day.

Members of the Alaska Department of Health and Social Services and the state Section of Epidemiology hosted a virtual press conference Friday to explain the backlog, the reasons behind it, and what other data sets are currently more helpful for understanding the true scope of COVID-19’s spread through Alaska.

The state reported 735 new cases of COVID-19, but no new deaths, on Friday, with 278 of them being reported for Wasilla alone. This large entry of new cases is the result of an ongoing data lag, members of DHSS explained, where staff members enter and publish the data as their work flow allows.

In its weekly case update, also published Friday, DHSS reported one part of this backlog was caused by a commercial testing lab in Anchorage — the one that started operating only recently — not reporting its test results to the state for at least four weeks. This, along with the fact that increased case diagnoses over the last few weeks has “exceeded the ability of public health to immediately report individual cases,” has resulted in what DHSS categorized as a “significant” underestimate of actual case rates in Alaska.

“Cases reported this week are an underestimate of true case numbers,” the weekly update reads.

The lab in question, Beechtree Diagnostics, conducted 13,169 tests, the results of which were not reported to the state until Nov. 25. Of those, 1,636 were positive. This delayed reporting is going to cause continued high numbers of new COVID-19 cases being added for the communities of Anchorage and the Mat-Su Valley, according to DHSS. Just over 350 positives for Anchorage and 880 for the Mat-Su have not yet been entered into the state data that is viewable on the coronavirus response hub.

Coleman Cutchins, a clinical pharmacist leading the state’s testing efforts, said the delay in reporting from the Anchorage lab was not intentional.

“I think it was a mix-up up in terms of how they were supposed to report to (the Section of Epidemiology),” Cutchins said. “They’re a new operation — they’ve never done this type of testing. They operate labs in Utah, so we’ve been told, but not doing PCR testing.”

The people who tested positive, and their providers, were notified of results within 48 hours, though, Cutchins said. The delay in reporting did not result in a delay of patient or provider care, he said.

One of the main factors behind the state’s ongoing data backlog is personnel, or lack thereof. Dr. Louisa Castrodale, an epidemiologist with DHSS, said “it’s absolutely a resource situation.”

“We are trying to recruit more folks for data entry,” Castrodale said.

She explained that the number of new COVID-19 cases that get reported by the state each day is more reflective of the data entry work force and its resources at the time.

“If we’ve got a really fast network that day and we’ve got a lot of hands working, we can get those numbers and we can really chew into the backlog there,” Castrodale said.

Delays in case reporting also hinge on local clinics doing testing, she said. If a clinic in a community experiences resource issues or staff shortages, their reporting of test results to the state will be delayed, which further extends the amount of time it takes for those results to get reported out to the public.

Asked whether there are any barriers to recruiting more data entry staff, Division of Public Health Director Heidi Hedberg said there are no limitations on how many extra people the division can bring on to help with the caseload. There’s also no shortage of people applying to the position, she said.

“But we’re really looking for individuals who have critical thinking skills,” Hedberg said. “Somebody that can look at paper faxes, they can look at electronic submissions and then be able to push … the various information into various data systems. So it’s the quality of the person that’s applying for the position.”

Hedberg said pay for these data entry positions is competitive. The Division of Public Health has expanded its work space, as well as telehealth.

Chief Medical Officer Dr. Anne Zink added that once new hires are brought on for data entry, it does take time to get them trained before they can begin helping address the backlog.

The data entry position is called a COVID technician and health associate, and those interested can apply at governmentjobs.com/careers/alaska?keywords=public+health.

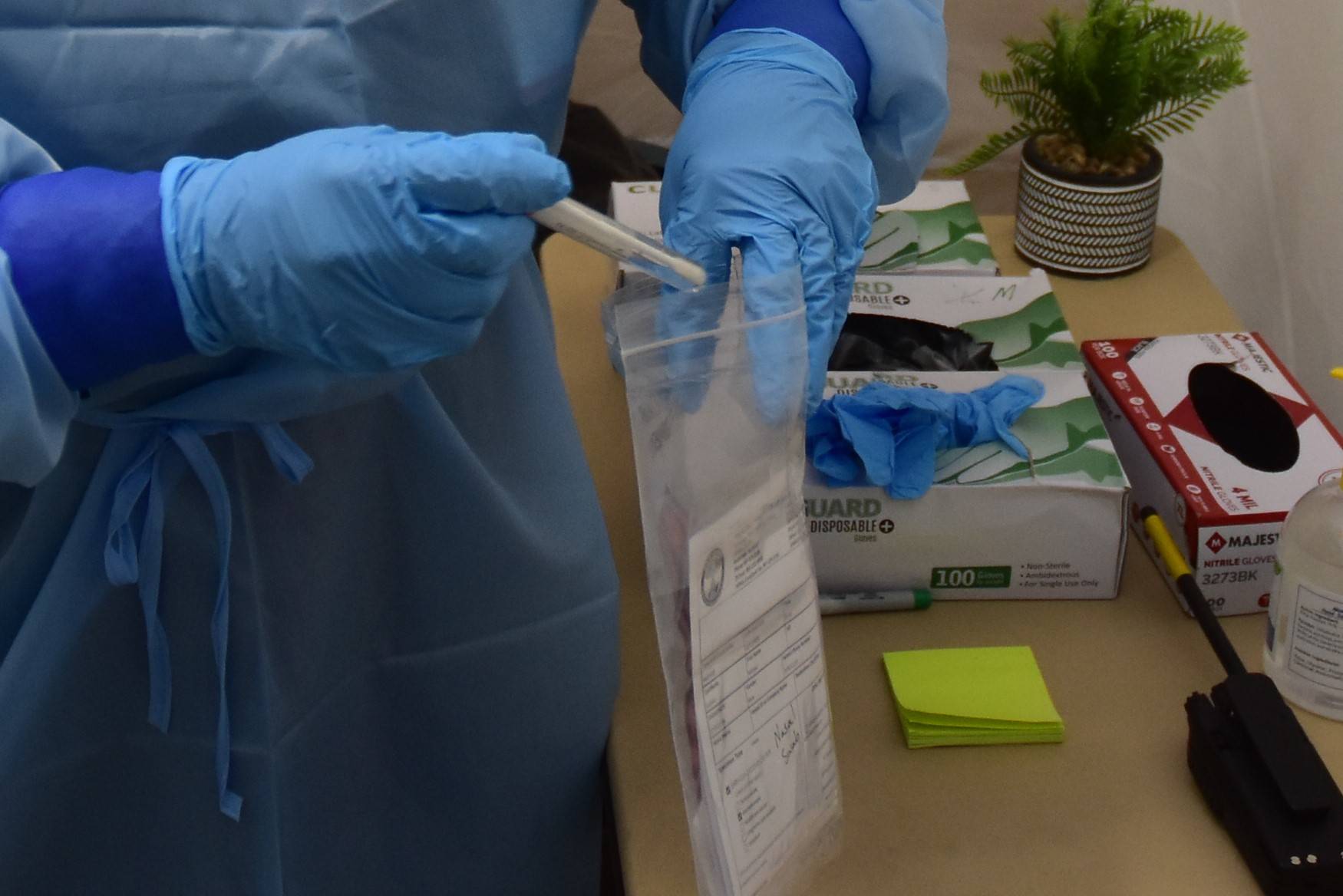

As DHSS data entry staff catch up on the backlog, they receive newly reported cases, validate them to ensure there are not duplicates, and then enter them as confirmed cases of COVID-19 on the state’s data dashboard, said Megan Tompkins, with the Alaska Division of Public Health.

To get a more accurate picture of how COVID-19 is spreading in their community, Alaskans should look to the onset dates of new cases, rather than the dates they were reported.

“That’s just a much more accurate representation of what’s happening in the communities,” Zink said.

She included the caveat that the onset dates of the most recently reported cases won’t always have an identified onset date yet.

Zink said that Alaska is not alone in having a taxed COVID-19 data reporting system. States across the country are experiencing similar data delays, she said.

More useful than the daily case number reports, Castrodale said, is the certainty that there is continued acceleration of the virus in Alaska.