The state must now address the fact that excessive motor boat traffic in July has made a section of the lower Kenai River too muddy.

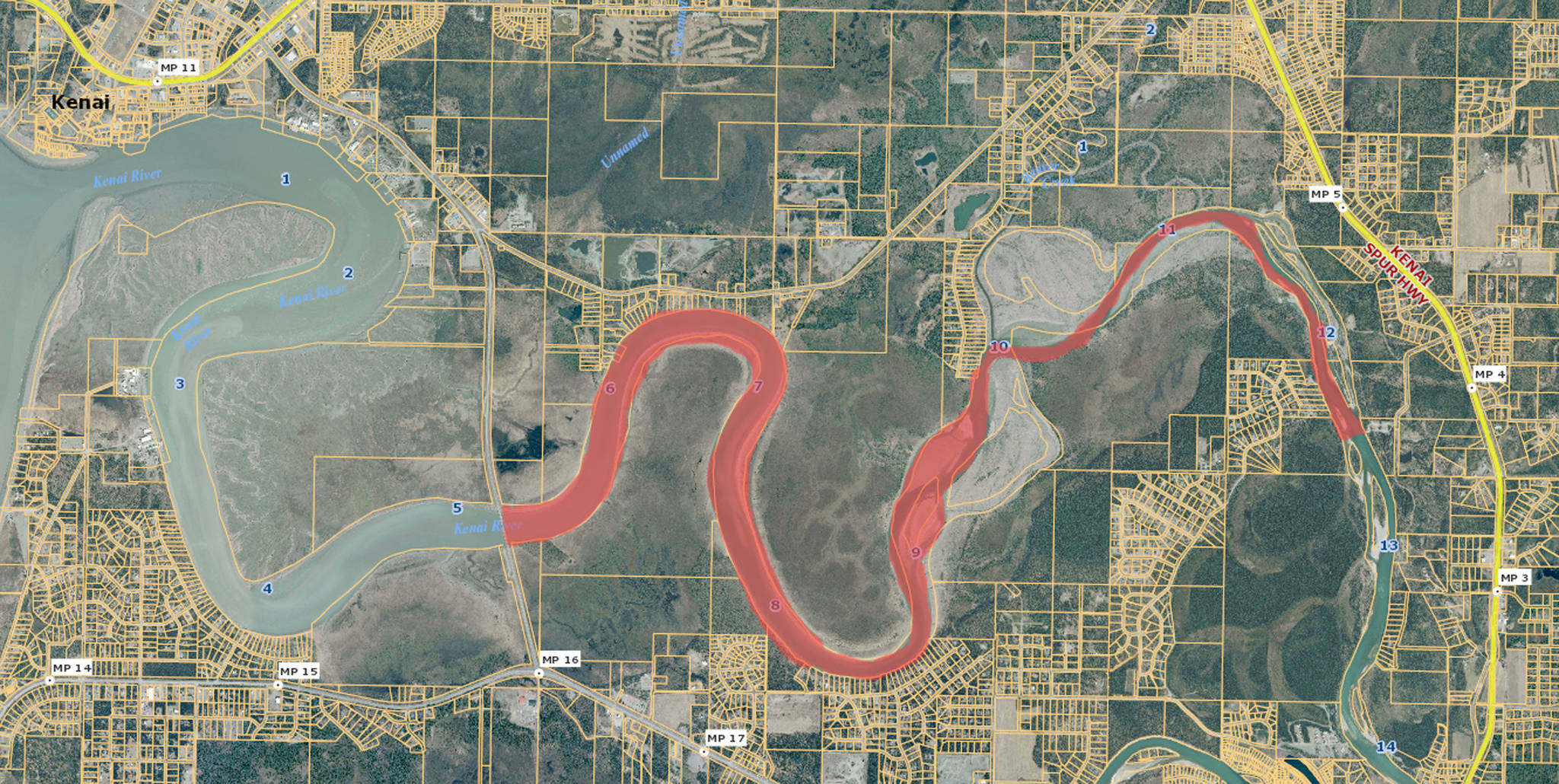

The Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation released a long-delayed report Thursday concluding that about 7.5 miles of the lower Kenai River exceeds the water quality standards for turbidity, or the measure of how much sediment or organic material is suspended in the water column. The result is that the water becomes more and more opaque and less light permeates into the river from the surface.

The river only exceeded the turbidity standards in one section, and only in the month of July, during the highest traffic fisheries on the Kenai River. The measure was high enough to exceed the baseline measure, but not enough to exceed the amount judged as damaging to fish and aquatic wildlife.

Under the category 5 designation, DEC would have to develop a recovery plan for the river. What that plan would look like depends on public input, said DEC Division of Water spokesperson Cindy Gilder in an email.

“DEC works with stakeholders to develop recovery plans,” she wrote. “This often includes hosting meetings to discuss our findings and investigate options for restoring the water. Sometimes we prepare a draft plan and then get stakeholder input. Until DEC has data showing water quality standards have been met, the status of the water remains the same.”

The report is still just a draft. DEC is seeking public comment on the draft from now until Jan. 29, 2018. After the public comment period is over, it will be submitted to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which requires the report to be done under the federal Clean Water Act, which will finalize the designation.

The state’s review of the public comments can take between three and six months, and after it is submitted to the EPA, the EPA has 30 days to take action, said EPA Region 10 spokesperson Bill Dunbar in an email. The agency can approve or partially approve what the state submits, after which the EPA has 30 days to make any corrections to the list. After that the agency goes out for its own comment period, he said.

“However, more often than not, due to the increasing volumes of data, the complexities associated with the data and assessment methodologies and increased public awareness and participation — and more comments to review — it very often takes longer than 30 days to come to a final decision on a list,” he said.

That was part of what took so long on the DEC’s determination, Gilder wrote. DEC originally contracted with Soldotna-based environmental nonprofit the Kenai Watershed Forum to test the turbidity levels in the Kenai River from 2008–2010, taking measurements at river miles 23 and 8. After the nonprofit submitted its results to the agency, radio silence ensued for the next few years, with some updates in 2011 and 2012 as the agency worked on it.

“In addition to meetings with EPA, DEC worked on guidance documents (Listing Methodologies) on how to make impairment decisions for both Turbidity (completed Sept 2016) and Petroleum Hydrocarbons, Oils, and Grease (completed Dec. 2015),” Gilder said. “Data needed to then be re-evaluated based on the guidance documents.”

Robert Ruffner, the former executive director of the Kenai Watershed Forum when the nonprofit conducted the turbidity studies, said he was surprised at the sudden release of the determination after so many years.

“I was pretty frustrated back then when we were presenting the data,” he said. “It wasn’t acknowledged, maybe, or it wasn’t given the scrutiny that it probably should have been. … So fast forward, I’m not in the same job, now it all comes out and I wasn’t expecting this.”

Previous studies and the DEC’s report identify high motor boat traffic in July as the cause of the increased turbidity. Some turbidity is natural, coming from upstream sediment load moving downstream, but the high motor boat traffic exacerbates it in the highest traffic areas of the river. The area indicated by the DEC for Category 5 designation is one of the highest traffic areas, including two major lower-river boat launches and multiple popular king salmon and sockeye salmon fishing areas in July.

Dwight Kramer, who chaired the Kenai River Special Management Area Advisory Board’s River Use Committee for several years, said it was good news that the turbidity issue was confined to a relatively small section of the lower river, but that it still held implications for salmon health.

Some studies have shown that when water is excessively cloudy, it can increase predation risk for juvenile salmon and make it harder for them to spot food in the water.

“The thing about the turbidity issue is it isn’t going to get better,” Kramer said. “It’s only going to get worse. There’s going to be more demand on the river. (Personal-use dipnet fishery boaters) are going to figure out that they can avoid the calamity (of the Kenai City Dock) if they launch further upriver and drive down. The king fishery is only going to continue to come back. … It’s up to the state if they want to try to nip this thing in the bud while they still can.”

Kenai River Special Management Area Advisory Board chairman Ted Wellman said the board hadn’t had the chance to review the full paper yet or provide comment but planned to discuss it at the upcoming meeting in January. The turbidity level isn’t high enough to affect fish health, which was good to know, Wellman said. The river has had other water quality issues in the past, including hydrocarbon pollution, that were more troubling, Wellman said.

“I was much more concerned about hydrocarbons and fecal coliform and things than it being a little muddy once in a while,” he said. “That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t think about it and we shouldn’t address it. If it can’t be mitigated in any way, then maybe we have a limitation on the number of boats in the fishery at a given time.”

Though the river is naturally turbid due to upstream sediment, Ruffner said all the Kenai Watershed Forum’s data showed that the river is outside its natural conditions in July. Though the DEC should be concerned about exceeding a quality standard and should work out solutions, remedies should be commensurate to the scale of the problem, he said. Multiple studies over the years have pointed to excessive motor boat traffic causing bank erosion, hydrocarbon pollution and noise issues, among others, which raise the question of how much traffic the river can take, he said.

“All of those point to a carrying capacity question,” Ruffner said. “Are we at the point where we need to have a serious conversation about it?”

Reach Elizabeth Earl at elizabeth.earl@peninsulaclarion.com.