The Alaska SeaLife Center’s resident female Steller sea lion, Mara, is pregnant, and she could give birth as early as this spring.

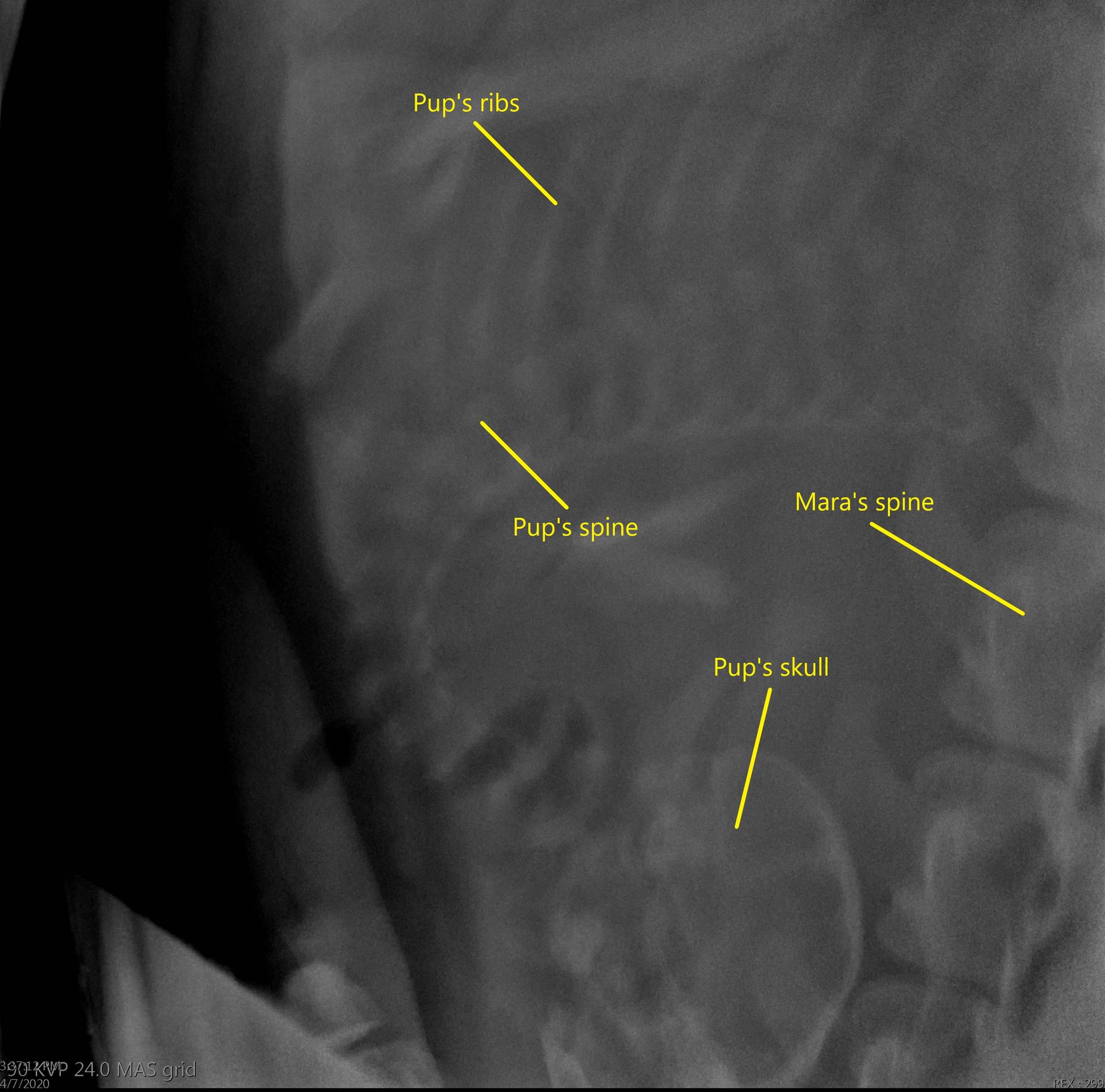

“Estimating a delivery date is imprecise in any species, but in Steller sea lions it is even harder since we have only tracked a few pregnancies,” Dr. Carrie Goertz, director of animal health at the SeaLife Center, said in a Thursday press release. “Nevertheless, I expect Mara to give birth earlier than all of our other births since I was able to detect the developing pup about a month before other cases.”

Mara is a 17-year old Steller sea lion and will be only the second of her species to give birth at the SeaLife Center. Lisa Hartman, husbandry director for the SeaLife Center, said on Thursday that Mara is a little on the older side for a Steller sea lion — most only live to their early 20s in captivity — so they don’t plan to breed her again.

Hartman said that Steller sea lion pups stay with their moms for at least a year after being born, so if all goes well, visitors will be able to see Mara and her pup once the SeaLife Center is able to reopen to the public. The sire, or father, of Mara’s pup is Pilot, a 10-year old male at the SeaLife Center

In the past, the SeaLife Center has been host to four other Steller sea lion births, all from another female named Eden who now resides at the Mystic Aquarium in Connecticut. Hartman said those births were part of a study recently published in the Aquatic Mammals Journal that looked at the effect of cortisol levels, a hormone associated with stress, among female Steller sea lions like Eden during mating and pregnancy.

“The Alaska SeaLife Center is one of only three aquariums in North America that house Steller sea lions,” Hartman said in the press release. “We are optimistic that the birth of Mara’s pup will continue to contribute to the understanding and knowledge base of this endangered species. This pregnancy and birth also contribute to the collaborative management of this species.”

The study found that animals trained to voluntarily participate in health care had lower cortisol levels than animals that have to be restrained, so mammalogists at the SeaLife Center train Mara and other aquatic mammals to be familiar with medical equipment through frequent ultrasounds and radiographs in order to keep her stress levels as low as possible. Hartman said that is also accomplished by gradually introducing the equipment into the animals’ exhibits so that they eventually become desensitized to it.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Steller sea lions have been listed under the Endangered Species Act since 1990. In 1997, NOAA made a distinction between the western population and the eastern population of the species. The western population, which includes Alaska Steller sea lions, is still endangered, while the eastern population has since recovered.

The SeaLife Center is currently closed to the public to help lessen the spread of COVID-19, but livestreams of the exhibits are available on the center’s YouTube page.