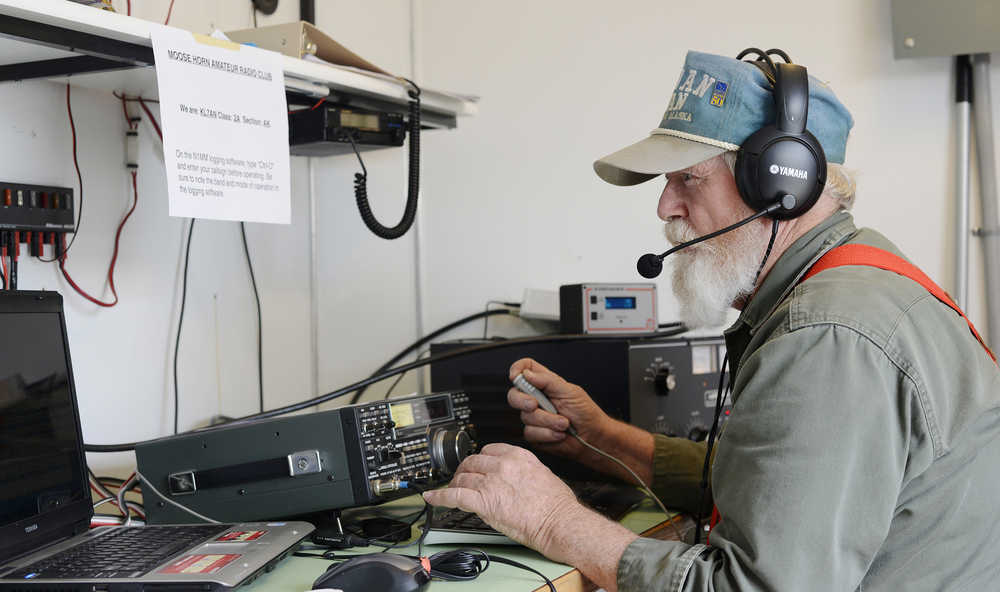

About a dozen people spent the better part of their weekend in the parking lot of Skyview Middle School in one of two trailers belonging to the Soldotna-based Moose Horn Amateur Radio Club. One trailer contained a pair of radio consoles, a bank of generator-charged car batteries to power them, and a pair of bunks for their operators — the other a home-made antennae tower that can be erected with a hand-cranked winch.

A second tower was set up by hand nearby, allowing club members to work the two radios from 10 a.m Saturday until 10 a.m Sunday in a marathon 24-hour competition to contact other operators around the northern hemisphere. By the end, they had exchanged call signs with 326 other amateur radio operators from places including Canada, Mexico, Indiana, Hawaii, Texas, Florida and Connecticut.

Moosehorn club member Chuck Kuhlman described the event as “useful play.” Member Ryan Christman said the goal was “to set up and operate portable stations, to demonstrate our abilities, and to have fun in the outdoors.”

In a world with ubiquitous cell phones and internet, the towers and car batteries of amateur radio seem crude. But this heavy equipment is the opposite of the fragile, invisible infrastructure on which such miraculous modern communications depend — an infrastructure that can be easily damaged by disaster or attack. The pair of trailers allows the Moosehorn club to set up an emergency HAM radio station anywhere they can park.

“We have different methods of communication now, but radio in one form or another is still important,” Moosehorn member Al Hershberger said. “Other methods of communication can be disabled, so although there are many other alternatives now, I think it’s still a good backup.”

The first ham radio field day was organized by the American Radio Relay League in 1933. Locally, the Moosehorn club also has a long history.

Hershberger said he got his first radio while fighting as artilleryman during World War II. It was a “volksempfänger,” or “people’s receiver,” commissioned by Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels and distributed to German citizens in the 1930s and 40s. After “liberating” the radio, Hershberger said he began messing around with it while off-duty.

“I’m curious,” he said. “When I see something that I don’t how it works, I want to know how it works … I swapped the tubes and stuff like that, and I looked inside and tried to see how it worked.”

After the war, in 1948, Hershberger found himself in Kenai, where he said he started fixing radios for fishermen.

“The commercial fishermen used battery-powered radios, and they listened to get the openings and closings of the commercial fishing seasons, when they could fish and when they couldn’t fish,” Hershberger said. “For commercial fishermen in Cook Inlet, the radio was a vital thing. I fixed a lot of those.”

Hershberger said he “just kept playing with radios, until I finally went into business,” opening a radio and TV repair shop in Soldotna in the 1950s.

He joined the local club, which was then the Wildwood Station Amateur Radio Club, after the Wildwood Air Force Station that once occupied much of the present area of Kenai. Hershberger said he still has the hand-drawn membership card of the Wildwood Club. When the military base disbanded, the group changed to its present name.

When the Good Friday earthquake struck in 1964, destroying telephone lines between Alaska and the outside world, Hershberger and fellow club member Ed Back became two of the radio operators on the Kenai Peninsula working to relay messages to the rest of the country.

“We were sending messages from the bowling alley the first night (after the earthquake),” Hershberger said. “Then I went back to my house, where I had a more powerful antennae. We didn’t have power the first night, so we were running off of generators … People would come to us and bring messages, give us a phone number of somebody living somewhere in the States, and say ‘Tell them I’m okay.’ We could talk to a ham who was close by, and he would get on the phone and call that person and give the message … After the first day, my voice was so sore I couldn’t hardly talk. It happened Friday night, and by Sunday evening we relaxed.”

Hershberger also sent messages for fire departments and other civil defense agencies during the 1969 Swanson River fire. Technological changes since Hershberger started fooling with radios have touched the ham world as well. Some members of the Moosehorn club now connect their laptops to their radio transmitters, using protocols that allow them to send digital files with the same signals other operators still use for morse code.

Nationwide, the American Radio Relay League has around 160,000 members in its affiliated clubs, according to the group’s website. A regional radio club based in Washington D.C won last year’s field day competition by making 9,700 contacts in 24 hours. Christman said success in radio often depends on the environment.

“Some people try to contact all 50 states and all the Canadian provinces,” he said. “But it all depends on the current radio conditions — the solar condition of the sun affects how short-wave radio works, and that affects how productive we can be.”

Club member Ed Seaward said he can usually send a signal to the Lower 48, but getting signals is much harder. Christman said Alaska’s latitude sometimes creates problems for radio.

“Being this far north, the ionosphere — which is what affects our radio signals — acts differently than it does further south, closer to the equator,” Christman said. “It bends radio waves kind of like a prism … Since we also have extremes of daylight and darkness, that also affects which bands work better at different times of the day. And the aurora completely shuts us down when it’s very active.”

However, Alaska does have what could be called a cultural advantage in radio sports.

“People find it interesting to contact us as opposed to other locations,” Christman said. “For the sake of contesting, field day, and some other activities, (Alaska) is considered in the ham radio world as almost a separate country. We are sought after in contesting, and for people to talk to generally, because we’re so far away.”

Reach Ben Boettger at ben.boettger@peninsulaclarion.com.