ANCHORAGE — More shrubs moving onto Arctic tundra because of climate change will have minimal effect on many of the bird species that breed there, but birds likely will seek other habitat when the shrubs grow tall, according to a new federal study.

A study by the U.S. Geological Survey concludes that the size of the shrubs was more critical than the density in determining whether birds would continue in the habitat.

“Height came out to be the most indicative of bird habitat selection,” said Sarah Thompson, a USGS research wildlife biologist based in Anchorage and the lead author of the study.

Multiple studies have shown that tundra areas are getting more shrubs, Thompson said. Climate warming also is having effects in the form of longer growing seasons, thawing permafrost and more frequent and intense wildfires, the authors said.

“All across Alaska, you see this kind of shrub encroachment into places that previously didn’t have shrubs or didn’t have tall or many shrubs,” Thompson said.

The researchers over three summers studied 17 bird species on the Seward Peninsula,which juts 200 miles into the Bering Sea in western Alaska and includes the city of Nome. The peninsula, Thompson said, is ideal for study because it includes coastal habitat and inland settings at a variety of elevations. It’s also along the transition between boreal forest and tundra, Thompson said.

“We can look at all these different kinds of habitats that might exist in different amounts in the future and see where birds are, and then we can project forward,” she said.

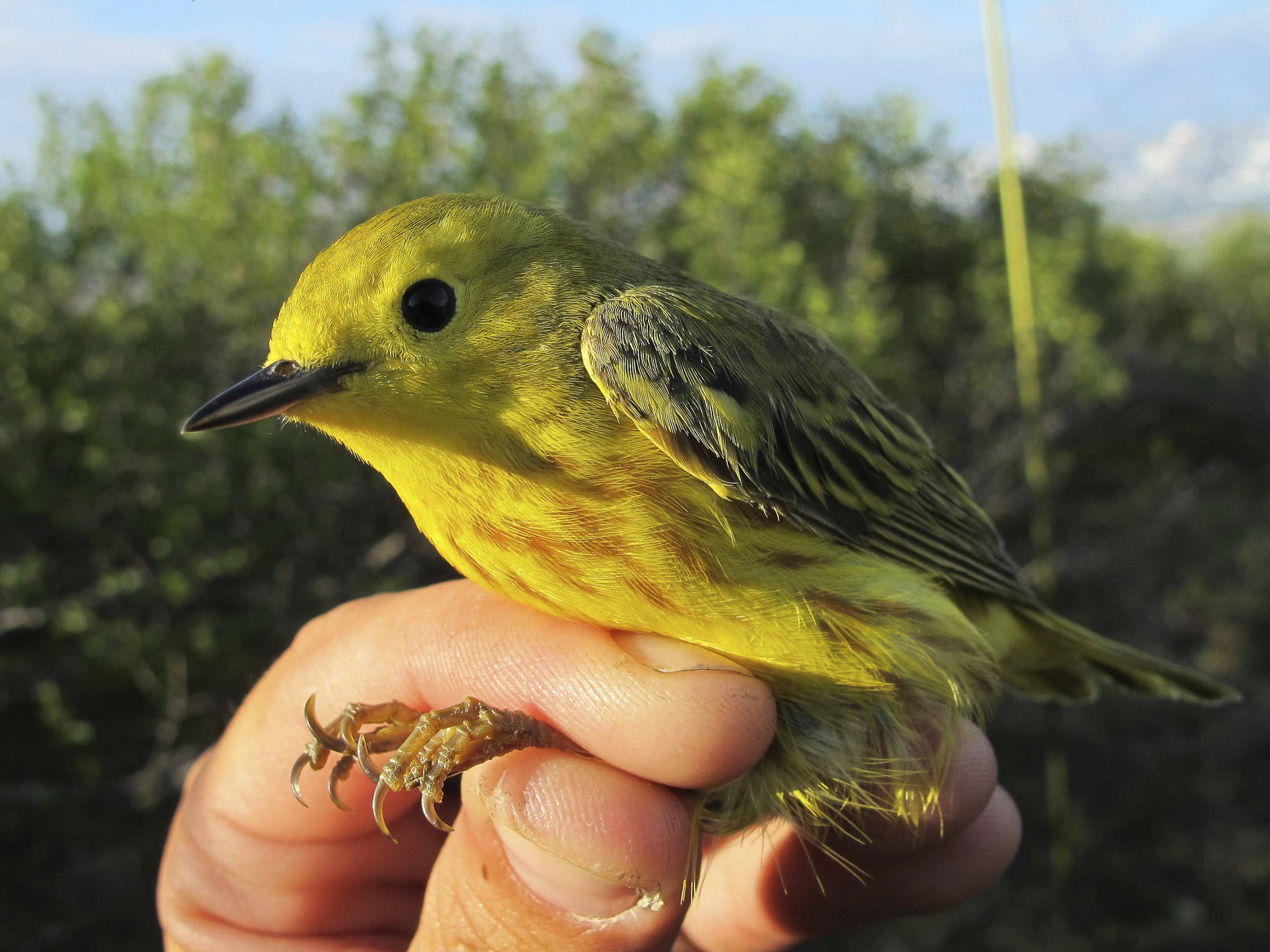

The 17 birds ranged in size from songbirds, such as the bluethroat, which flies in from Eurasia, to wading birds such as whimbrel and bristle-thighed curlews that fly in from other parts of North America to breed on tundra. The birds time the hatching of their eggs to the height of insect season, Thompson said.

The research did not attempt to explain why tall shrubs made tundra less appealing to birds, such as effects on nesting or insects. That likely will be addressed in future studies, she said.

George Divoky, director of the nonprofit Friends of Cooper Island, who has studied Arctic seabirds for more than four decades off the coast of northern Alaska, said the study is one more piece of evidence that the warming Arctic is having effects both at sea and on land to avian populations.

However, he said, the paper only emphasized shrubs instead of other important factors affecting birds on the peninsula, such as warmer temperatures and birds’ dependence on seeds and insects.

“They should have been going out ever since, certainly, the 1990s when climate change got to be an issue, and doing plots and actually measuring the changes in these birds, rather than going out now, and saying, ‘Oh, by the way in the future, these things are going to happen,’ ” Divoky said.