Editor’s note: This article has been clarified to show that the Kenai Peninsula Borough School District’s Students in Transition Program assisted 185 students in the central Kenai Peninsula.

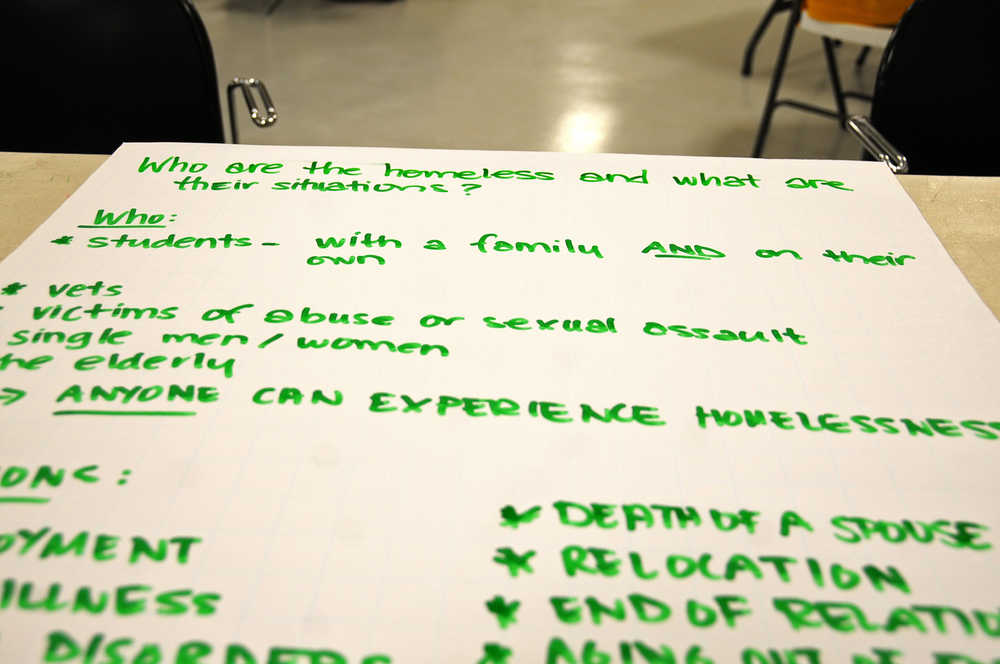

When a group of community members tried to come up with a list of who becomes homeless at a workshop Wednesday night, one phrase appeared multiple times in the results: “Anyone can experience homelessness.”

Asked what the effects were, the common answer was that homelessness is a drain on community resources. But when asked what to do about it, the answers were less clear. More housing was mentioned repeatedly, as was more support from the community.

A new organization, Kenai Peninsula Journey Home, is trying to answer the question of what to do about homelessness. In a community workshop held Wednesday at the Alaska Army National Guard Armory in Kenai, about 25 community members gathered around tables to discuss homelessness on the central Kenai Peninsula and how to handle it.

A group of behavioral health workers in the Kenai and Soldotna areas conceived the idea for the organization over lunch one day last year. Georganne Roberts, Margene Andrus, Michelle Lesiagonicz, Beth Selby and Stephanie Haasis all see the effects of homelessness in their jobs and decided to work collaboratively to do something about it.

Homelessness on the Kenai Peninsula has historically been hard to track. The only organization that keeps continual track of its homeless population is the Kenai Peninsula Borough School District, which offers assistance for homeless students through its “Students in Transition” program, which served approximately 185 students in the central Kenai Peninsula in 2015. No other local agency does a count of the community at large.

In 2007, Soldotna nonprofit Love INC requested a study from the University of Alaska Anchorage’s Institute of Social and Economic Research to estimate the annual homeless population on the peninsula.

The researchers estimated at the time, using a summer survey, that between 400 and 500 people were homeless on the peninsula each year, though “the overall homeless population is difficult to enumerate because of their transience and because oftentimes a state of homelessness is variable and/or temporary,” according to the study.

In 2015, 31 homeless people were living in shelters in Kenai, 28 were not living in a shelter and 10 people lived in transitional housing, five of whom were veterans and 13 of whom were younger than 18 years old, according to a May 2016 point-in-time count by the Institute for Community Alliances, the contractor operating the Alaska Homeless Information Management System, a statewide data collection survey.

But that number is a bare minimum, not including people who choose not to seek out resources, who were missed in an official count or who may be in one of the nebulous homelessness circumstances like couch-surfing with friends, Selby said.

“(That number is) at least how many there are,” she said.

One of the most immediate needs is for additional housing. Only two emergency shelters currently operate on the central peninsula — the LeeShore Center, which offers services for women and children who were victims of domestic violence or abuse, and the Friendship Mission, which offers Christian-based services for men. There are no shelters for children, families, former Alaska Department of Corrections inmates or general shelters for men. For every 1,000 residents in the Kenai Peninsula Borough, there are 1.64 year-round emergency shelter, transitional housing and permanent supportive housing beds, according to a 2015 inventory from the Alaska Coalition on Housing and the Homeless.

“Our problems on the peninsula are Alaska’s problems,” said Catherine DeLacee, funding and development director for Love INC, said at the Wednesday workshop.

DeLacee said the number of homeless individuals on the peninsula has likely increased since Love INC commissioned its study on the population. The organization used to operate a shelter for families without housing but had to close the shelter in 2013 due to a lack of funding.

Federal funding exists to encourage communities to develop these resources. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development grants funds to local nonprofits, state agencies and local governments through its Continuum of Care program to provide housing, support housing programs and promote self-sufficiency among people experiencing homelessness. Local nonprofits Love INC and the LeeShore Center have received funds for their housing projects in the past.

LeeShore Center Executive Director Cheri Smith said at the meeting that public and agencies alike should be involved with the Continuum of Care process to enable local organizations to get funding for projects. The next meeting for the program will be held Oct. 6 at Love, INC, and she encouraged everyone to attend.

“If your community is not strong and working together, you’re not going to get funded,” Smith said.

Attendees broke out into small groups to discuss three questions for 20 minutes at a time, including identifying who the homeless are on the peninsula, defining the community effects of homelessness and naming current resources available for those without a home. To facilitate conversations, participants would move from group to group, never sitting with the same people twice.

The conversation style lends a cooperative dialogue, said Mary Elizabeth Rider, who coordinated the discussion at the event. Afterward, she said she will take all the notes from the evening’s discussions and synthesize them together. Another workshop on the same topic was scheduled for Thursday evening, open to the public.

“We’ll be talking about the same things, so come again (Thursday) night, and bring two friends,” Rider encouraged the attendees Wednesday.

Reach Elizabeth Earl at elizabeth.earl@peninsulaclarion.com.