Up until last year, Southeast Alaska’s Mitkof Island was home to a creek with some unique salmon: they only turned left. Officially, anyway.

Ohmer Creek, on Mitkof Island, forks. On the west side, the state’s Anadromous Waters Catalog, or AWC, had noted the presence of all five species of wild Alaska salmon, as well as Dolly Varden and cutthroat trout. On the east side of the fork, according to the AWC, there were only steelhead.

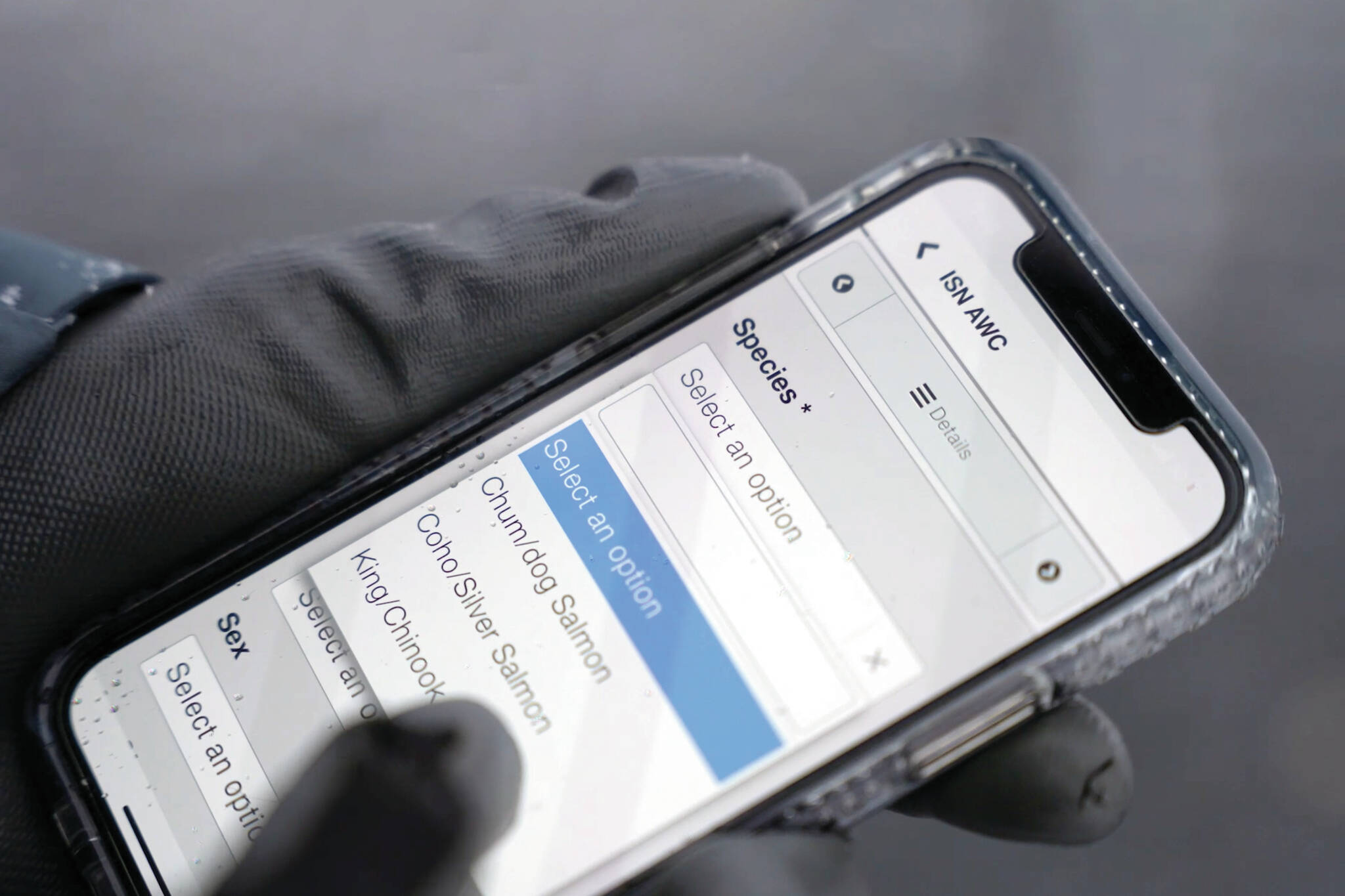

One afternoon last summer, Petersburg Ranger District fish biologist Eric Castro pointed out juvenile coho salmon holding steady in the current about his feet on the undocumented fork of Ohmer Creek. He, hydrologist Heath Whitacre, and Taran Snyder, a Natural Resource Specialist working with the Forest Service through VetsWork by AmeriCorps, set out some minnow traps, caught coho, cutthroat, and Dolly Varden, took some photos, and set about correcting the record via a new app downloadable to your phone: the Fish Map App.

“It’s really fun,” Castro said. “We use our tablets, and we’re able to capture this information for posterity. It’s a game-changer.”

This year, people behind the app hope that in addition to the Tribes, forest partnerships and experts who used the app last year, everyday Alaskans will download and use the app — and earn $100 for each successful nomination.

Anadromous waters

“In Alaska, there are a ridiculous number of lakes and streams that probably, at least if they’re connected to the ocean, support some sort of anadromous fish,” said Network Program Officer at the Alaska Conservation Foundation Aaron Poe, who works on the app through the Northern Latitudes Partnership. (Partners on the app include the Alaska Department of Fish & Game, the Fish and Wildlife Service, Northern Latitudes Partnership and the Aleut Community of St. Paul Island Tribal Government, which made the app possible through their Indigenous Sentinels Network.)

According to the Alaska Department of Fish & Game, “The Catalog of Waters Important for the Spawning, Rearing or Migration of Anadromous Fishes and its associated Atlas (the Catalog and Atlas, respectively) currently lists almost 20,000 streams, rivers or lakes around the state which have been specified as being important for the spawning, rearing or migration of anadromous fish. However, based upon thorough surveys of a few drainages it is believed that this number represents a fraction of the streams, rivers, and lakes actually used by anadromous species. Until these habitats are inventoried, they will not be protected under State of Alaska law.”

The usual estimate is that those 20,000 streams, lakes and rivers are about ⅓ of Alaska’s anadromous waters — leaving ⅔ of salmon, eulachon, trout, whitefish and other anadromous fish-bearing streams without a basic level of protection.

“Even in urban or town-based settings, there are opportunities to get things mapped,” Poe said.

Citizen Science in action

Last year, the Yakutat Tlingit Tribe, the Prince of Wales Tribal Conservation District, and Petersburg Ranger District of the Forest Service documented and nominated about 10 miles of habitat between Wrangell, Petersburg and Kake, as well as a previously unmapped anadromous tributary on East Ohmer Creek. The AWC, Poe said, averages between two and three citizen science nominations each year.

“Even just by launching this app, we got 13 more. But we’d love it to be 1,300 more,” Poe said.

Each of those nominations, if successful, will earn the nominator $100. $100 will be paid for each successful nomination, whether it results in a new stream or not. So the same section of stream could be nominated for, say, coho, sockeye and cutthroat, as long as those fish were not previously noted there.

Sitka Conservation Society and SalmonState Fisheries Community Engagement Specialist Heather Bauscher, who conducted much of the field testing and many of the trainings in 2022, will continue trainings this summer. She hopes, she said, “to connect more with Tribal community forest partnerships and youth crews who are out in the field and know these places best.”

Poe noted that climate change adds a new element to the catalog. “With the rapid and accelerating climate change that Alaska is facing, fish are moving to different habitats, and they’re leaving other habitats. So not only do we have this huge system, we have a huge and dynamic system. Streams in the Northwest Arctic – we need to be able to document those kinds of changes that are becoming a refuge-type habitat for anadromous species,” he said.

Citizen science, Castro said, is “something that’s underutilized in our land management practices. There are plenty of people who walk up these streams and know that there are anadromous fish there. And now they have the ability to help be a part of this process of increasing the knowledge of our state’s anadromous waters.”

Mary Catharine Martin is the communications director of SalmonState, an Alaska-based organization that works to ensure Alaska remains a place wild salmon and the people whose lives are interconnected with them continue to thrive.

How to document anadromous waters:

Download the ISN AWC app on your phone.

Sign up.

Follow the instructions to start documenting and submitting nominations. Photos of sport-caught anadromous fish, wild salmon, trout or other species in the streams, juvenile fish, and even spawned out carcasses work. Species must, however, be clearly identifiable.

Additional resources:

Go to www.alaskafishmapping.org for more information and guidelines.

Text “fish” to: 1-855-736-4949 and you’ll get an automated response asking you what area you’re interested in mapping. Reply with a community name — “Bethel,” “Anchorage,” “Cordova,” etc.) and you’ll get a text with the current AWC map of the area.

Those who want trainings — community groups, volunteer activities, schools or sports teams seeking fundraising opportunities, as a few examples — should reach out to Poe for more information. apoe@alaskaconservation.org.