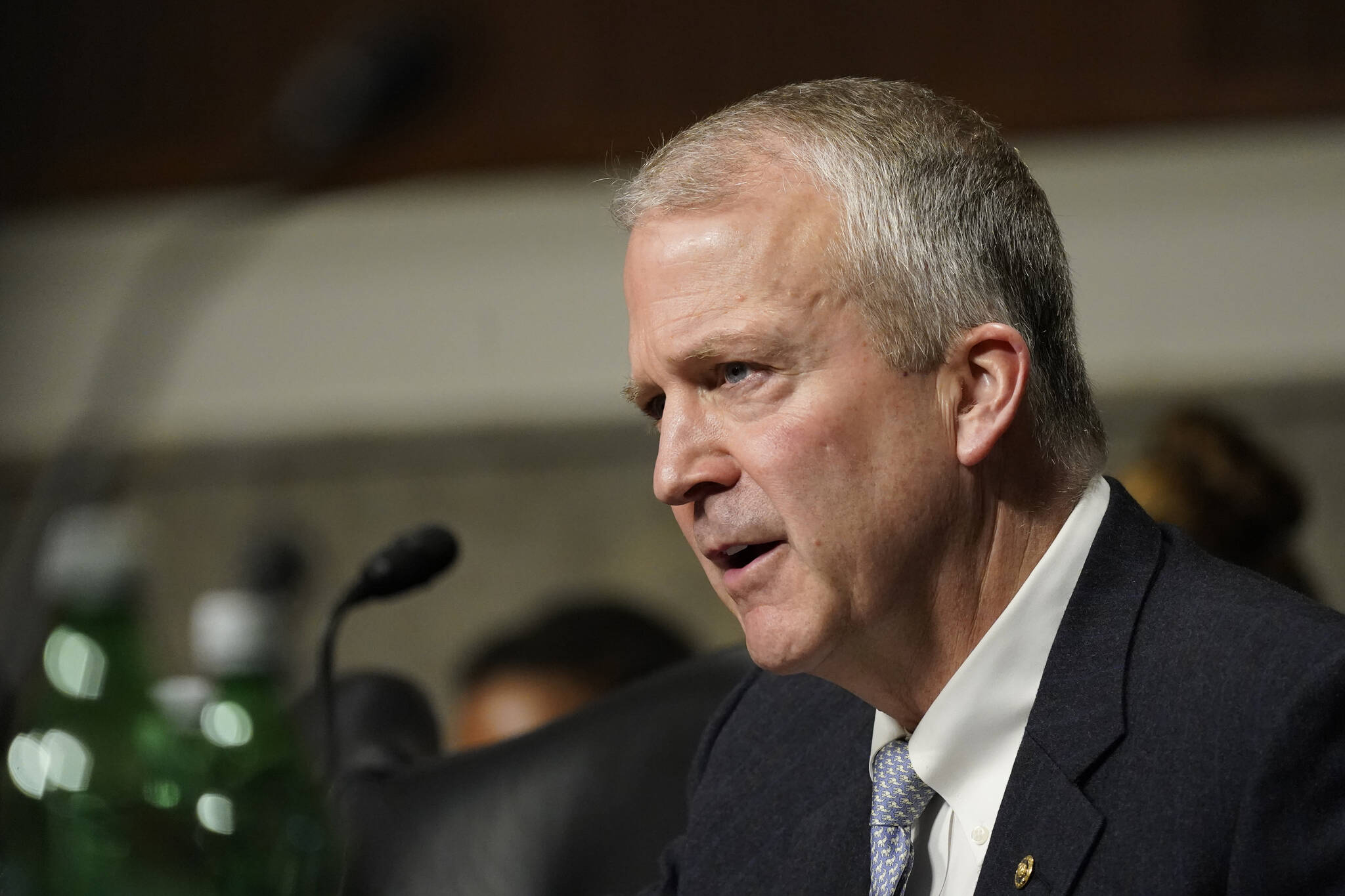

Before Sen. Dan Sullivan voted against the Fiscal Responsibility Act, he praised House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) for “his hard work in getting President Biden to negotiate a debt ceiling agreement that averts a default, reduces wasteful spending and authorizes critically-needed permitting reforms.” Then he complained the agreement inadequately funds the U.S. military.

Sullivan’s reference to wasteful spending is a subtle echo of the failed strategy Gov. Mike Dunleavy applied to Alaska’s budget woes in 2019. It’ll take a lot more than ending government waste and inefficiencies to solve the debt problem.

The Fiscal Responsibility Act meets the minimum implied by its title. The U.S. government won’t default on its debt obligations. But while the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates it will reduce the federal deficit by $1.5 trillion over the next 10 years, the annual deficit this year alone is about the same amount. And the total national debt is a staggering $31.4 trillion.

Sullivan would have supported the bill if his amendment to add $18.4 billion to the Department of Defense budget had passed. It’s not as if DOD is a model of fiscal responsibility though. Its infamous purchases of $600 toilet seats and $400 hammers in the 1980s were embarrassing headlines. Far worse is how after 30 years of audits, DOD still can’t account for about 60% of its $3.5 trillion in assets. And according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, the cost overrun to maintain its F-35 fighter fleet will exceed $100 billion.

Those aren’t concerns of conservative researchers at the Heritage Foundation. “Allegations of fraud, waste, and abuse have always plagued defense contracting,” they wrote in a 2008 report. Eliminating it “is an obligation of government, and rightfully so.” But they also argued it’s been “historically proven to be a relatively modest source of savings compared to the overall defense budget.”

Across the board, waste and inefficiencies are indeed a small part of the recurring budget deficits. Inadequate revenue screws up the government’s bottom line too. And Republican sponsored tax cuts are a big part of that problem.

In my lifetime there are only four years in which the federal government had an annual budget surplus. It was during the second term of Bill Clinton’s presidency. The “peace dividend” which followed the end of the Cold War allowed for significant defense spending cuts. Congress passed moderate spending reductions on other programs. And a booming economy brought in additional tax revenue.

But Clinton also increased revenue by raising taxes. And his budget numbers got a boost from previous tax hikes enacted by his predecessor, George H.W. Bush.

Congressional Republicans weren’t expecting a surplus when they enacted the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. But ignoring Congressional Joint Committee conclusions, many of them, including Sullivan, claimed it would generate enough economic growth to offset the loss of tax revenue. Later, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office pegged the 10-year increase to the federal debt from the tax cuts at $1.9 trillion.

In 2001, the Republican-led Congress passed a tax cut that turned the surplus Clinton handed them back into a deficit. Then in 2003, while the country was fighting wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, they irresponsibly did it again.

But “Reagan proved deficits don’t matter,” former Vice President Dick Cheney reportedly said to Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill, who opposed the second round in 2003. “We won the midterms. This is our due.”

The tax cuts enacted under Ronald Reagan are the largest in U.S. history. And by the end of his second term the annual budget deficit had almost doubled.

To please voters, Republican rhetoric now alternates between the need to balance the budget when a Democrat occupies the White House. And cutting taxes when a Republic is president even if it means increasing the deficit. In a sense they’ve given Americans a partial tax holiday for 40 years. And for too many that’s enabled the expectation of a relatively free ride on the government programs and services from which they benefit.

It can’t last forever.

Holding the line on government spending is necessary to ensure future generations aren’t saddled with the enormous debt incurred under our watch. But until today’s taxpaying public is willing to pony up to help end deficit spending and settle America’s debt it’s an exercise in futility.