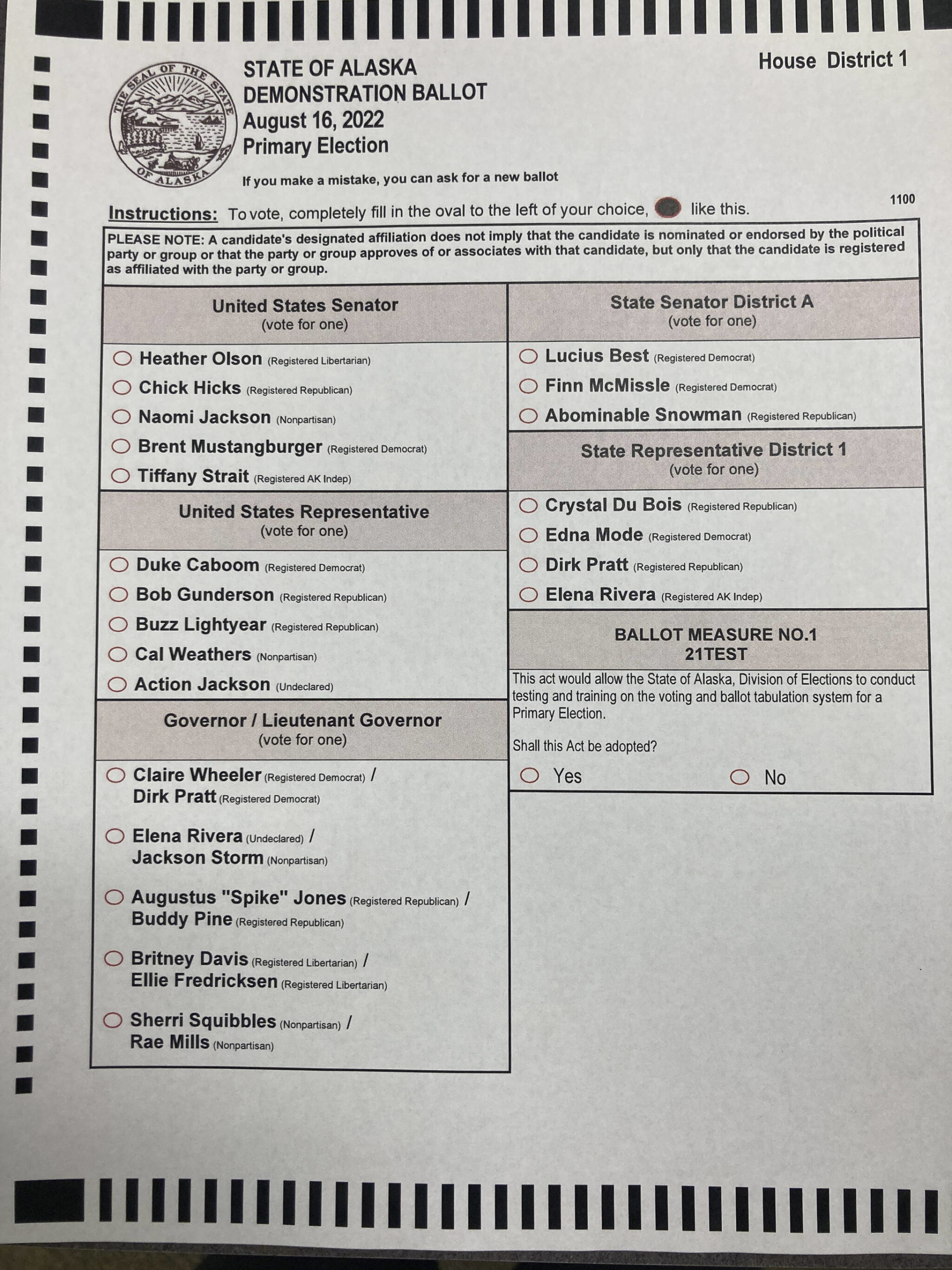

Last week, the state Supreme Court upheld the open primary voting system approved by Alaskans in 2020. The single ballot will list all candidates regardless of party affiliation. It will be open to all registered voters. The top four vote getters, regardless of party, will then compete in the general election where the winner could be decided by how voters ranked their choices.

This is a story about how voters in Alaska, as well as other states, retook control of primary elections from self-serving political parties.

In 1947, Alaskan voters approved a blanket primary for statewide elections. All candidates appeared on a single ballot, with the winner in each party appearing as that party’s nominee on the general election ballot.

In 1992, Alaska’s Republican Party sued the state to prevent candidates not registered as Republicans from seeking their party’s nomination in the primary. The presiding judge announced a tentative decision based on a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in a Connecticut case. It found that state’s primary laws violated the constitutional right of a political party “to enter into political association with individuals of its own choosing.”

A subsequent agreement between the state of Alaska and the Republican Party stipulated that one primary ballot would list only Republican candidates and it would not be open to voters affiliated with other parties. All other candidates would appear on a separate ballot.

The state was then sued by a voter. In 1996, the Alaska Supreme Court ruled the blanket primary did not violate the state Constitution.

That same year, Californian voters approved a blanket primary. But in 2002, a 7-2 ruling by U.S. Supreme Court declared it was unconstitutional. That resulted in Alaska reverting to the 1992 agreement.

The Democratic Party in Washington leveraged the 2002 ruling to overturn the state’s blanket primary which had been in use since 1935. Two years later, voters approved a “top two” primary system. It called for a single ballot for all candidates with only the top two vote getters, regardless of party affiliation, moving forward to the general election. Republicans, joined by Democrats and Libertarians, sued. But in another 7-2 decision, it was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court.

California adopted a similar primary system in 2010.

In the immortal words of Yankees legend Yogi Berra, it was “like déjà vu all over again” when our turn came in 2020.

The heart of the dispute in every one of these cases was the parties’ constitutional right of political association.

In writing for the majority in the California case, the late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia argued that forcing parties to open primaries “to persons wholly unaffiliated with the party” will likely result in “changing the parties’ message.” Furthermore, “It encourages candidates—and officeholders who hope to be renominated—to curry favor with persons whose views are more “centrist” than those of the party base.”

But since that ruling, if not before it, closed primaries resulted in equally dishonest campaign tactics. When competing against only members of their own party, candidates craft their message specifically for the base. Then, in an appeal to voters across the political spectrum, the primary winner almost always pivots to the center.

Later, in his dissent of the ruling upholding Washington’s top two primary, Scalia argued “the state-printed ballot for the general election causes a party to be associated with candidates who may not fully (if at all) represent its views,” which would then “color perception of the party’s message,” leaving “no space for party repudiation or party identification of its own candidate,” thus impairing “the party’s advocacy of its standard bearer.”

Donald Trump’s 2016 candidacy for president, which was in full bloom when Scalia passed away, proves the fallacy of that argument. Despite his many non-conversative views and un-Christian-like behavior, the Republican Party never repudiated Trump. Instead, its leadership vigorously campaigned for him.

If Scalia were alive to see Republicans downplay Trump’s attempt to overturn the 2020 election, he’d most definitely rethink his defense of the freedom of political association. They’ve made mockery of that and numerous other constitutional laws.

Alaska’s new election laws is an opportunity to improve our experiment with self-governance. But only if ‘we the people’ take that responsibility more seriously than the parties do when dishonorably courting our votes.

• Rich Moniak is a Juneau resident and retired civil engineer with more than 25 years of experience working in the public sector. Columns, My Turns and Letters to the Editor represent the view of the author, not the view of the Juneau Empire. Have something to say? Here’s how to submit a My Turn or letter.