In 1962, Rachel Carson published “Silent Spring” in which the horrors of pesticides like DDT were exposed. Her legacy prompted both government agencies and chemical companies to be more cautious in how pesticides are formulated and used, but it has also made many people fearful or even paranoid about pesticides.

At the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge we are also wary of pesticides, but we do use them to manage some of the more than 110 exotic plant species introduced to the Kenai Peninsula. Over the years, we have been spot treating invasive plants at trailheads and boat launches, keeping the refuge noticeably cleaner than the rest of the peninsula. We typically use three chemicals: glyphosate, aminopyralid and fluridone. These are the active ingredients in the different commercial herbicides we use to control or kill target species.

The big differences between DDT and other pesticides used in Carson’s time and those we use now are their environmental fate and how they degrade over time. DDT has a half-life (time required for half of the original concentration to degrade) of 2-15 years. DDT can also leach into water sources and bio-accumulate in the tissues of animals. In contrast, the three chemicals we use all have half-lives under a year, do not leach, and do not bio-accumulate in animals.

There has been a lot of bad press about glyphosate, but most issues with glyphosate products are associated with its use in agriculture where herbicides are applied chronically or genetically encoded into seeds. Glyphosate products vary in their formulations of glyphosate, the carrier solution, and surfactant. Surfactants enhance the active ingredient’s effectiveness by breaking surface tension of the liquid herbicide to improve its coverage of foliage, its ability to stick to foliage, and its rainfastness.

We typically use two glyphosate formulations for terrestrial weed control on the refuge. Aquamaster can be applied close to water. It is a liquid in which glyphosate comes as an isopropylamine salt and surfactants can be added. The more terrestrial formulation is Roundup ProMax, another liquid but the glyphosate comes as a potassium salt and surfactants are already included. Interestingly the surfactants prepackaged in Roundup products, deemed “nonactive” ingredients and not regulated by U.S. EPA, are actually 100 times more toxic as cellular disruptors than glyphosate itself. Once we finish our current supply of Roundup ProMax we will use Aquamaster exclusively as our glyphosate product since we add a fairly benign surfactant called AGRI-DEX.

Both Aquamaster and Roundup ProMax affect only the emergent foliage to which it is applied. Glyphosate inhibits amino acid synthesis, which stops the production of three amino acids necessary to make enzymes and other proteins. Any glyphosate that reaches the soil binds tightly with sediment until it degrades by microbial action and so is not absorbed by roots. Its average half-life is 44-60 days in the soil. Because it binds so tightly with the soil, glyphosate is unlikely to leach into groundwater.

The other terrestrial herbicide we use is Milestone with the active ingredient aminopyralid. Unlike glyphosate, aminopyralid remains active in the soil after application for the duration of the growing season so any target plants that emerge after the initial application will also be controlled. Aminopyralid does not move much in soil, remaining in the top 6-12 inches after application. Aminopyralid is a synthetic auxin (growth regulator). Its average half-life is 35 days in soil where it is primarily broken down by microbes. In water, aminopyralid is quickly broken down by sunlight (photolysis) with a half-life of less than 1 day. At the rate we apply Milestone, 90 percent of the herbicide is gone from the soil in the first 90 days.

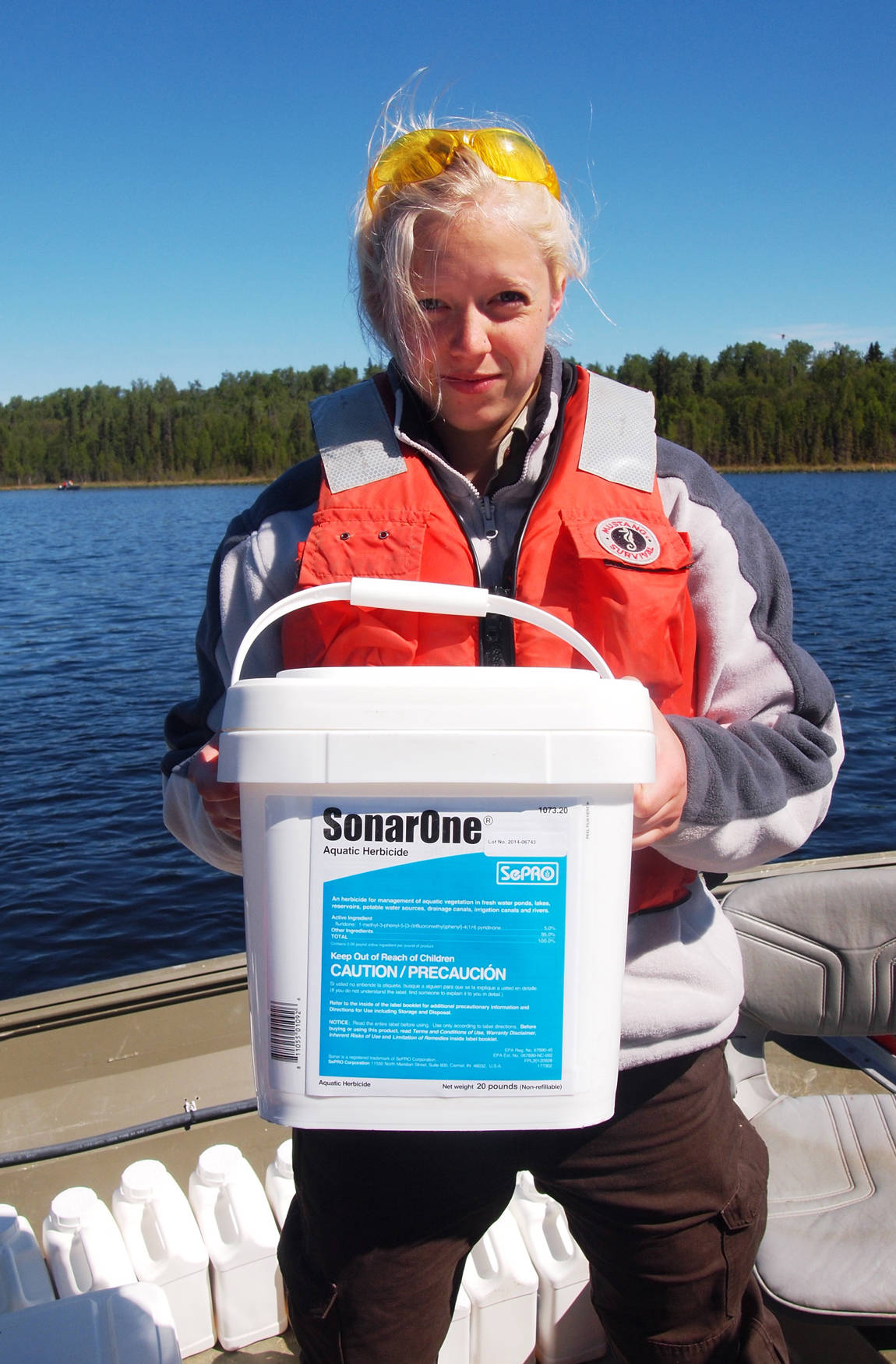

The only aquatic herbicide we use has the active ingredient fluridone, applied as both a slow-release clay pellet (SonarONE) and as a liquid in an oil-based emulsion (Sonar Genesis). This herbicide has been instrumental in our fight with Elodea, Alaska’s only introduced aquatic invasive plant. It is applied at extremely low concentrations (less than 10 ppb) with a long contact time (45-90 days) that is lethal to Elodea but not so to native plants. Fluridone inhibits the biosynthesis of carotenoids, essentially shutting down photosynthesis. In the water column, fluridone is diluted by water movement, plant uptake, sediment adsorption, photolysis and microbial degradation. In sediments, after reaching its maximum concentration 1-4 weeks after treatment, it then degrades by microbial action.

At the Kenai Refuge our goal is to eradicate or contain invasive species, not just control their populations. We believe in detecting infestations early and responding quickly. Herbicides are one of the first tools we use, not because we are “chemical happy”, but because they are generally the most effective tool when eradication is the goal. Treating early when infestations are small means we ultimately use less chemical with a greater likelihood of success. We are careful to use herbicides and surfactants that are both effective and have few secondary effects.

And a word to the wise: Always follow the instructions on the product label. Often times when herbicides don’t appear to work, it’s probably not the chemical. It’s much more likely they were applied on an inappropriate species, at the wrong rate, during the wrong time in the growing season, or in the wrong weather. When in doubt, call the product manufacturer or Janice Chumley at the UAF Cooperative Extension Service in Soldotna (907-262-5824).

Kyra Clark is a seasonal biological technician at Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. Find more information about the Refuge athttp://www.fws.gov/refuge/kenai/ or http://www.facebook.com/kenainationalwildliferefuge.