Just over a year ago, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game applied the pesticide rotenone to two lakes and a stream in the remote Miller Creek drainage on the northern Kenai Peninsula to eradicate the last known population of invasive northern pike on the Kenai Peninsula.

Before the treatment, ADF&G, Kenai Watershed Forum and other partners caught hundreds of native rainbow trout and other fish from these waters, which they transported to a nearby pond. Over the following months, the rotenone dissipated, so ADF&G released the rescued fish back into the system this past spring.

It was not possible to rescue the countless snails, insects, zooplankton and other freshwater invertebrates, which the returning fish would need for food. Many of these invertebrates are susceptible to rotenone, so they likely were affected along with the pike. We wanted to know: How did the invertebrates fare?

Before the planned treatment, teams from ADF&G and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service collected invertebrates in Vogel Lake, North Vogel Lake and Miller Creek to catalog the kinds of invertebrates that lived there. We scooped the shallows with D-nets, towed plankton nets through the open water, and plumbed the lake bottoms with grab samplers to find as many kinds of little animals as we could.

We identified many specimens the old-fashioned way with microscopes, good identification guides and plenty of patience. Most of our vials were full of invertebrates, which we sent off to a lab for metabarcoding.

At the lab, the samples were ground up, and DNA from the mixtures was sequenced, yielding lists of species present in the samples.

Unfortunately, we later learned that the lab apparently could only process a small volume of material from each sample, so they only processed some of our samples, and the rest were discarded. As a result, we detected fewer species than we might have.

We still documented 51 species of invertebrates. One of my favorite finds from the pre-treatment samples was the black spongillafly, a small relative of green lacewings that exclusively eat freshwater sponges.

I had looked for these years before, but I had not gotten to see one until poking around at Vogel Lake. It turns out that spongillaflies were pretty common out there.

I enjoyed learning about zooplankton, which was new for me. Jelly waterfleas, one of several kinds of waterfleas we found, secrete blobs of jelly around themselves to deter other things from eating them.

They look like soaked chia seeds. When they detect predators, the jelly waterfleas make even more jelly around themselves. Another common waterflea out there grows spines for the same purpose.

These little invertebrates need their defenses because many other animals eat them —even other waterfleas! Ghost fleas lurk invisibly in open water thanks to their long bodies that are extremely clear except for their tiny eyes.

These predacious crustaceans nab other unsuspecting waterfleas while stealthily hiding from larger animals. I had no idea that plankton were so interesting! I hoped that we would find these same species after the rotenone treatment.

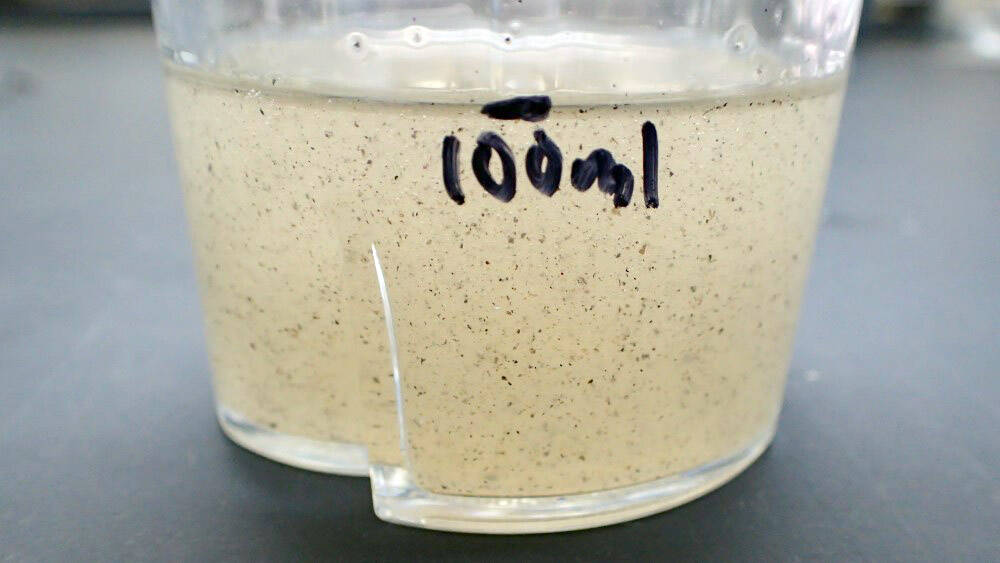

We returned to the same places the following year and collected the same kinds of invertebrate samples to find out how the invertebrates were doing. However, this time we ground up our invertebrates in a kitchen blender and mailed only a small volume (about 2 teaspoons) of blended invertebrates from each sample to the sequencing lab.

The idea is that even a small portion of each blended sample should include tiny bits of all the species that had been in the original sample.

The kitchen blender worked well. I still need to go through the new data, but so far, we have found 92 species of invertebrates post-treatment, including most (33) of the species that we had documented pre-treatment.

It was good to see that waterfleas, black spongillaflies, dragonfly nymphs, caddisflies, stoneflies, mayflies, worms, fingernail clams and other invertebrates remained plentiful in the lakes and Miller Creek.

This year’s most interesting additions were parasitic worms like Australapatemon burti, a fluke with a long name and a complex life cycle. Each one of these worms must first live in a freshwater snail, then leave the snail and infect a leech.

If a duck or swan eats the leech, then the fluke can reach maturity and produce eggs in the bird’s intestines. The eggs get into the water in the waterfowl’s droppings.

My favorite post-treatment find was Echinorhynchus salmonis, a spiny-headed worm that lives in freshwater shrimp in its early stages. Then, after a fish eats the shrimp, it infects the fish. It parasitizes rainbow trout, salmon, sculpins and other fish, but they are generally not harmed much.

We found some invertebrate species, like Harris’s diving beetle, only once before treatment, so we might have just missed them post-treatment. Other common species, like the Yukon floater (a freshwater mussel) and the common forestfly (a stonefly) that we failed to find afterward, may have become scarce due to the rotenone treatment.

Thankfully, even if these species were truly absent, they are capable of quickly recolonizing from nearby waterbodies.

While some short-lived invertebrates, like the waterfleas, might have survived the rotenone treatment as eggs, it was noteworthy that long-lived invertebrates, like marsh ramshorn snails and darners (a kind of dragonfly) lived through the rotenone treatment.

I was glad to get out and find so many invertebrates at Miller Creek this year for my own enjoyment in seeing them, for their sakes, and for the hundreds of hungry native fish that are pursuing them. It was satisfying that the watershed appeared to be returning to the productive trout lakes that they had long been.

Matt Bowser serves as a Fish and Wildlife Biologist at Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. Find more Refuge Notebook articles (1999–present) at https://www.fws.gov/kenai-refuge-notebook.