Editor’s Note: This is the third part of a series the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge is doing on the history of remote sensing and aerial photography for Refuge Notebook.

In Part I and Part II of this series, I shared the early history of aerial photography, how the military used aerial images extensively in World War I, and the development of its use in natural resource planning during the Great Depression.

Between World War I and II, aerial photography began developing into a science and profession known as photogrammetry. In 1934, the American Society of Photogrammetry was founded. It is known today as the American Society of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing.

The ASPRS defines photogrammetry as “the science and art of obtaining reliable measurements using photography.” Before the advent of computer technology, photogrammetrists used mathematical projection equations to produce maps from aerial photos taken with film.

Today, photogrammetrists can take thousands of digital images from their cameras and download them into special photogrammetry software that can quickly create digital three-dimensional maps. After downloading these maps into programs like Google Earth, anyone can view and analyze them.

Photogrammetry, as a science, started to develop significantly during World War II, which still lasts to this day. Aerial surveillance became so important in the war that the military formed specialized air photo interpretation teams to interpret aerial photos, record data and create maps.

At the same time, the U.S. military contracted with the Kodak company to develop film that would capture infrared images. The ability to take infrared aerial photos provided a significant advantage in the war.

Near-infrared photo film, called camouflage detection film at the time, would be used with great success to identify camouflaged enemy equipment, like tanks. The trees contained chlorophyll that reflects infrared radiation, which makes the trees in the infrared photo appear red. The camouflaged tanks appear in normal color, thus distinguishing the tanks from the surrounding vegetation.

After the war, in the late 1940s, the military’s photogrammetric capabilities were so useful that the U.S. government tasked the military with large-scale aerial photography missions. In Alaska, the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy photographed large blocks of land, producing the first statewide aerial photographs of Alaska. Some of the first topographic maps of the state were developed from these aerial photos.

While military geographers were conducting research on new techniques in aerial photography, infrared photo technology and multispectral cameras, they were struggling to come up with a term to describe what they were doing.

Finally, by the late 1950s, Evelyn Pruitt, a geographer with the Office of Naval Research, coined the term “remote sensing.” Eventually, remote sensing became the preferred term to describe the various methods by which scientists gather information about the surface of the Earth remotely without physically interacting with it. Aerial photography is now considered the earliest form of remote sensing.

In the 1960s and early 1970s, remote sensing started to see advancements in photo imagery not just from aircraft, but also from satellites that take images of the Earth across a wide band of spectral ranges. For example, a satellite with a multispectral scanner can capture multiple images at once by capturing different wavelengths across a wide range of the electromagnetic spectrum.

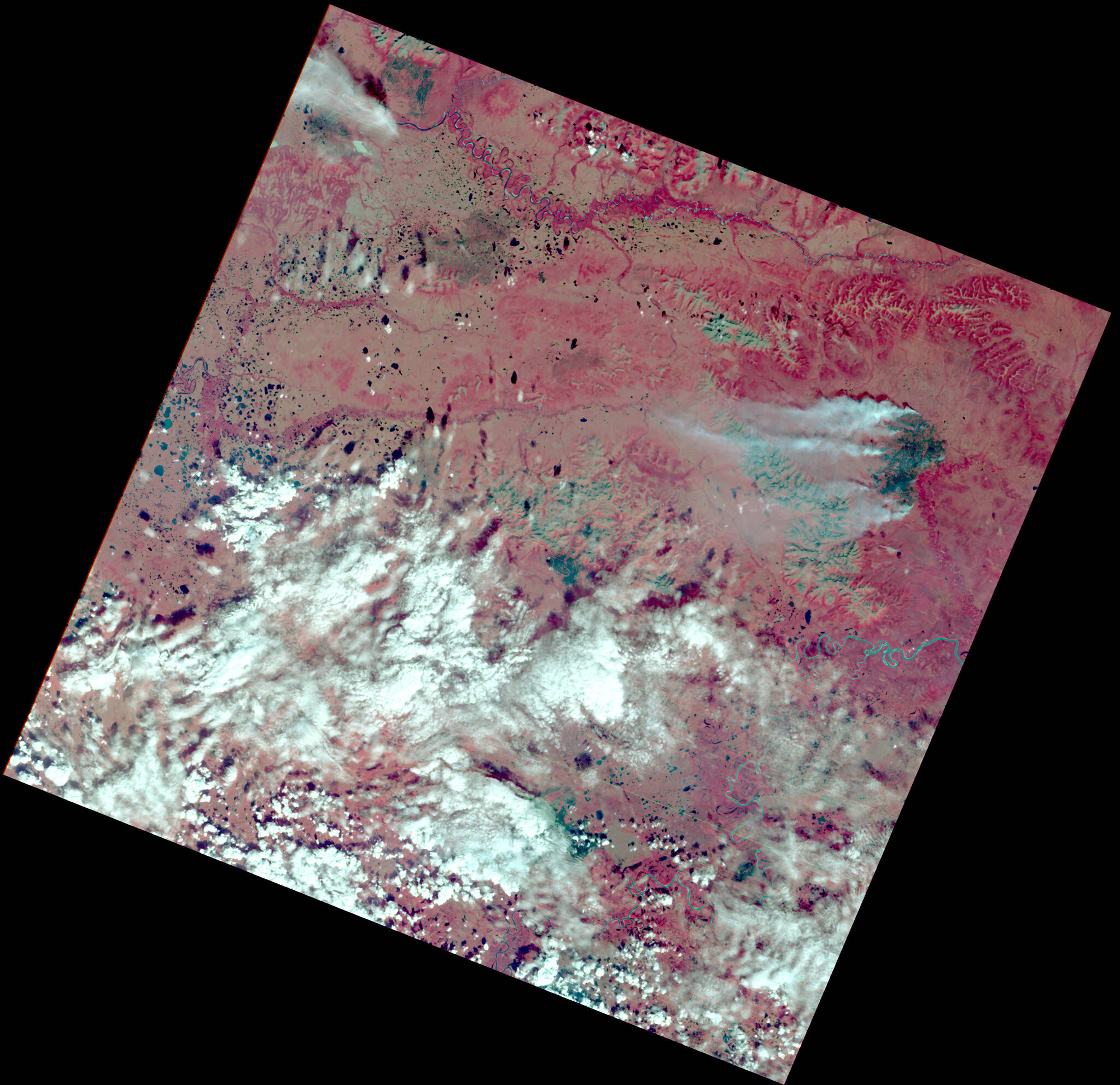

In 1972, NASA launched the first satellite, Landsat 1, specifically designed to collect this type of imagery to study planet Earth. In only a few days after the launch of Landsat 1, remote imagery revealed many unknown islands on Earth. One of those was named Landsat Island after the new satellite. The new satellite also produced stunning images of an 81,000-acre fire that was burning in a remote part of central Alaska.

The historic launch of Landsat 1 was the beginning of a new era in remote sensing, where aerial photography was no longer the domain of aircraft but could be taken from satellites in space.

By the mid-1970s and into the 1980s, every land management agency in Alaska was using remote sensing of natural resources for environmental assessment. For example, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service started the National Wetland Inventory mapping program in 1974.

The program’s purpose is to provide users with a resource that shows the extent and type of wetlands in the U.S. and Alaska. Color-infrared photos became the primary source for this mapping project.

In the 1980s, the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge, in cooperation with other federal agencies, acquired the first Landsat imagery of the Kenai Peninsula. This began a decadeslong vegetation mapping program on the peninsula that continues to be updated to this day. After the Kenai refuge was mapped, other refuges in Alaska started using similar remote sensing methods to map their refuges.

Scientists continue to experiment with remote sensing in ways that help them understand the environment better. Remote sensing today is used for a diverse range of scientific interests, including mapping wildlife habitats, wetlands and glacial retreats.

In the final article, Part IV of this series, I will write about the use of remote sensing today and how we use thermal imagery on the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge to better understand our environment.

Dave Merz is a seasonal biological science technician on the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge who is part of a team working on using aerial photography and remote sensing to understand changing environmental conditions on the refuge and throughout Alaska. Find more Refuge Notebook articles (1999–present) at https://www.fws.gov/kenai-refuge-notebook.