Recently a friend asked me for information about spruce grouse. I am sure he saw the slight look of panic as I thought about what resources I had and where the conversation would be headed.

I seriously knew little beyond what they looked like and how many could be harvested during the hunting season. I ran through my resources in my head.

If I want to know more about where they occur on the globe I turn to eBird. For taxonomy questions and distinguishing different subspecies I dig deeper for papers written since the expansion of DNA-based studies. If I am only interested in identification and tantalizing side notes on life history, I have five different field guides and two apps.

Unfortunately, the answer to a broad question is often more complex than the information being pursued. My first response usually entails more questions about the information being sought, in order to reduce my search time for information not needed. The arduous task of information gathering just got easier.

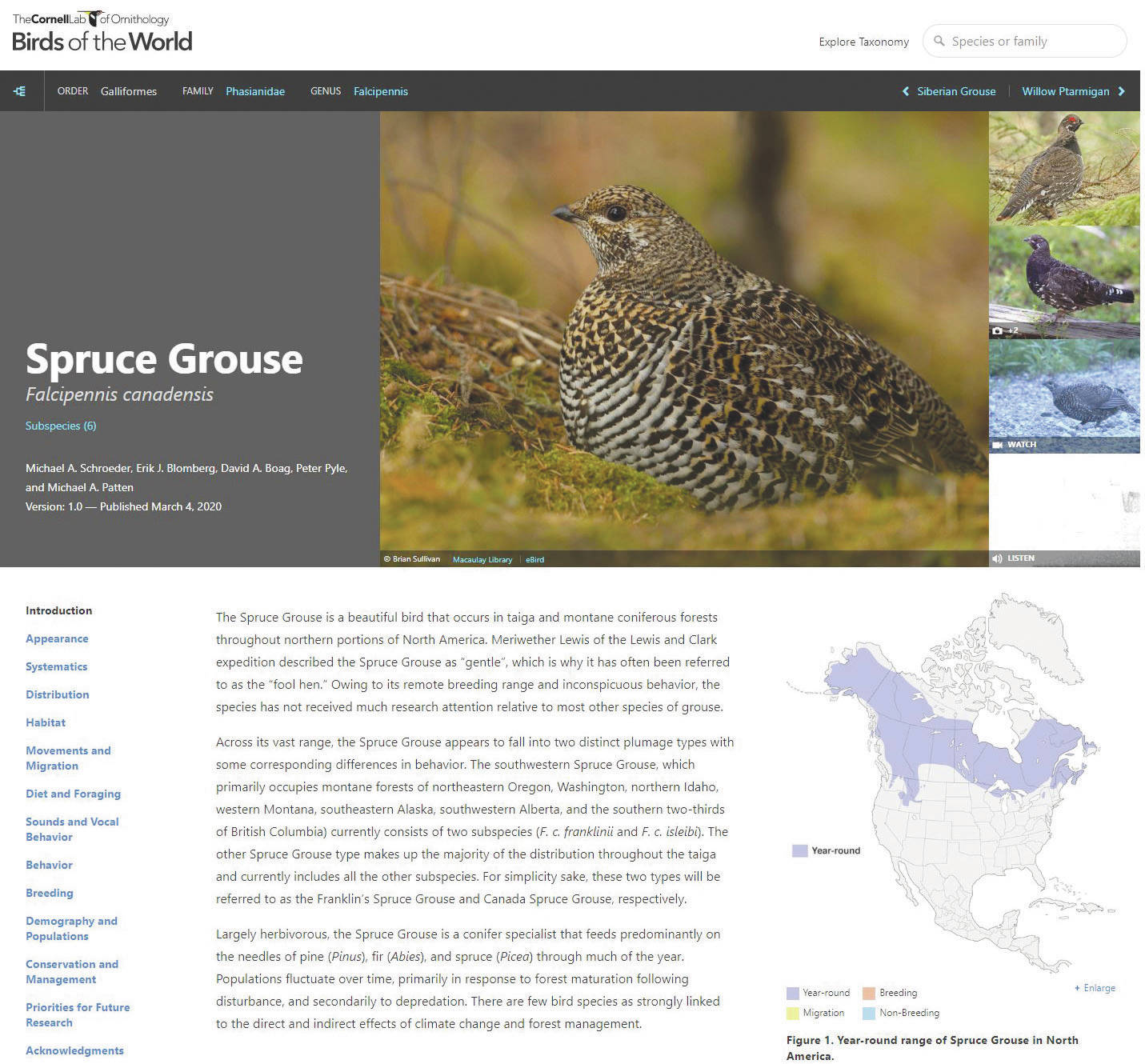

This week the team at Cornell Lab of Ornithology unveiled the most comprehensive source of bird knowledge we have seen in decades. After several years of development they launched a program called Birds of the World.

It follows along the same lines as the Birds of North America series, but goes way beyond. Currently there are 10,721 species that have been included in Birds of the World and new and updated species accounts are being completed regularly.

The volume of work that went into this is astounding. It integrates information from eBird, Cornell Lab of Ornithology Macaulay Library, and the Internet Bird Collection into one easy to use and navigate platform.

Ebird has over 700 million bird sighting records and is adding another 1.25 million daily. The Macaulay Library has over 16 million photo, video and sound recordings.

There are dozens of other apps that provide you access to information about songs, appearance, life history and such. Thayer’s Birding Software, eBird, Bird Journal, Scythebill and Birders Diary all have information available beyond just keeping a spreadsheet of the birds you have seen.

Some are free, some you pay upfront for the whole program, and others are subscription-based systems, such as Birds of the World employs. Some also provide institutional subscriptions so that your school or community library can provide access to users.

One of the things I found most impressive about Birds of the World is that many sections of the program are live-linked to the other sources of information. So as new sightings come in daily, the maps are also updated and I don’t have to wait for the updated version of the program to come out each year.

After pulling up spruce grouse info for my friend, I spent about 20 minutes glassing through species that I knew more about. There was tons of information I had never encountered. It would have taken me weeks to compile all of the information about one species and now I have info on nearly 11,000 species at my fingertips.

I entered my recent two favorite species, Anna’s and rufous hummingbirds. In a matter of minutes, I discovered fascinating info on the differences in their nesting strategies that explains why there are nesting Anna’s hummingbirds in the Seattle area right now.

Anna’s actually nest in what we consider late winter (November through May). Since they are less territorial about feeding areas this is presumably a strategy that reduces competition with more aggressive migrant species like rufous, who arrive in Alaska in early May.

When we finally document overwintering Anna’s hummingbirds on the Kenai Peninsula, we should expect them to start nesting sometime in March. Obviously, this winter was a reset back to our more “normal” temperatures. In subsequent winters, when we have more mild conditions, anything is possible.

How can a hummingbird nest survive even in the Pacific Northwest where cold, damp and occasionally snow are par for the course in February? In my review of Birds of the World, I found a cited paper that tested the thermal capacity of the nest structure. The author found the insulating ability of the nest to be slightly better than polar bear hair!

The inner cup is lined with hair, feathers and plant fibers. The walls of the nest are formed with fluffy plant material like cattail, willow and cottonwood fluff from their catkins, bound together with spider web silk. This forms the perfect insulation. The outside is carefully decorated with lichen and moss held on by more spider web silk, making it extremely camouflaged.

This is an amazing resource. I found digging through the information therapeutic as we enjoy the last of the winter and wait for migrant birds to return.

To preview Birds of the World and view a few of the free species accounts go to the following link: https://birdsoftheworld.org . I don’t think you will be disappointed and will likely have trouble extracting yourself from the computer, as I did.

Todd Eskelin is a Wildlife Biologist at Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. Find more Refuge Notebook articles (1999-present) at https://www.fws.gov/Refuge/Kenai/community/Refuge_notebook.html or other info at http://www.facebook.com/kenainationalwildliferefuge.

By TODD ESKELIN

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge