Thinking back to my childhood days in Alaska, I don’t recall wildfires being a regular occurrence. I’ve learned that I was uninformed at that time. I have since found that wildfires have a long history here and play a key role in shaping our landscape.

In mid-April of this year, I started as the Fire Management Officer at Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. Having grown up in Anchorage, summered on the Kenai Peninsula in my youth, and recreated across Southcentral Alaska, I couldn’t feel more privileged to be tasked with stewarding the lands where I grew up.

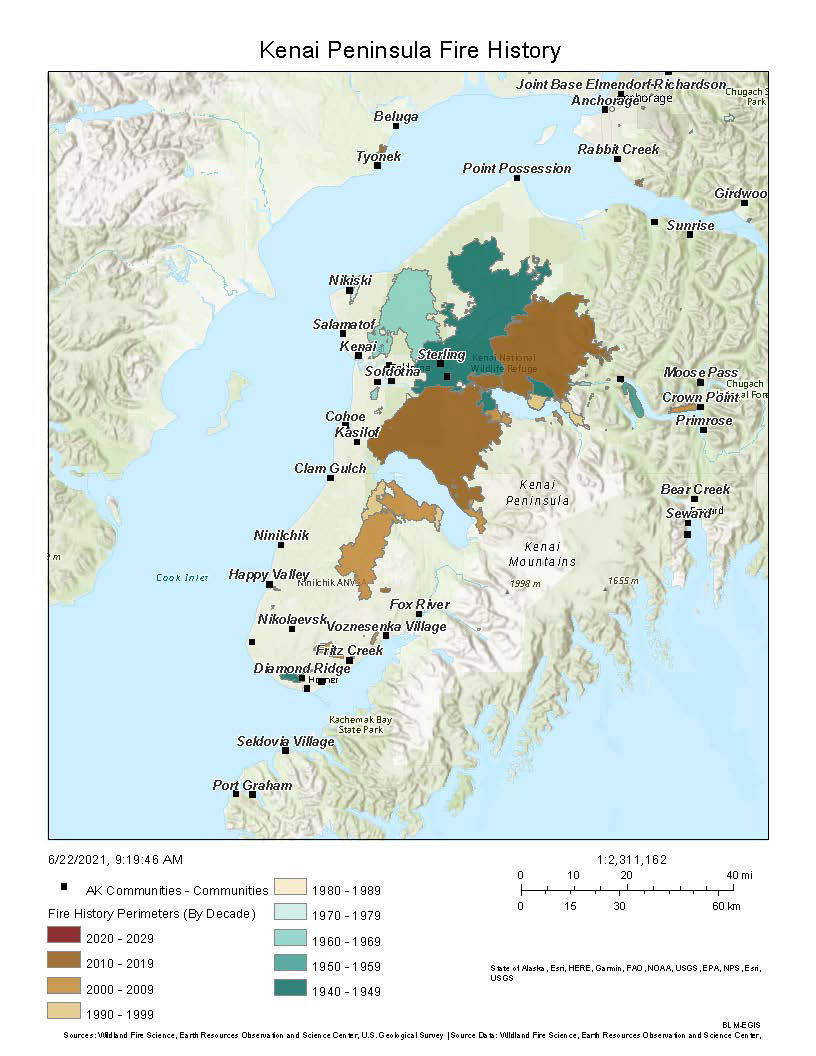

My first real exposure to wildfire was on the Kenai Peninsula as a teenager during the 1991 Pothole Lake Fire, an escaped campfire that consumed 7,900 acres of the refuge in mid-May. It was controlled by early June and was monitored for several months until ultimately declared “out” in late October of that year.

I was traveling down to the peninsula with my grandfather, and we witnessed a large column of smoke, followed by seeing active flames next to the popular Jim’s Landing. We were concerned, mostly about how it might affect our fishing trip, and were thankful that from what we knew, there weren’t any structures or campgrounds that could be at risk from the fire.

We were able to pull off the highway along with the other “rubberneckers,” as my grandfather would call them, to watch the fire burning on the south side of the Kenai River. We were completely unaware of the size of the fire or that it was burning along Skilak Lake Road as well.

Witnessing the smoke and fire was a new experience. It was loud and a little frightening. You could clearly see a significant change occurring on the landscape right in front of us.

Seeing this fire ignited an interest for me in becoming a firefighter. I wanted to help. The dirty, arduous work of protecting our natural resources also drew me in.

At that point, I believed that we needed to protect our forests from fire and put fires out quickly as they came along. I did not recognize the role that fire plays in keeping our ecosystems healthy, resilient and productive.

Since that time, I’ve had the opportunity to work for several land management agencies in different areas of the country. I’ve learned that we can’t put out every fire as they come along, nor should we try to suppress all fires.

In many areas, suppression of all wildfires has led to unhealthy forests. Heavy accumulations of hazardous fuels contribute to more frequent, larger and longer duration fires that are difficult to control and put us all at risk.

Instead, there needs to be a balance in how we approach fire management. Fires that are directly threatening our communities must be suppressed quickly to limit impacts.

Other fires will necessitate protecting property, improvements, critical wildlife habitats or valuable at-risk timber, and some should be allowed to play its role on our landscape.

Our fire seasons are becoming longer, we are experiencing more frequent lightning events and the number of large fires is on the increase. So, we must learn to live with fire on the Kenai Peninsula.

Fire is a natural part of our forests. When forests mature, fire returns, creating new and early successional forests that benefit our resident wildlife. Fire can also be destructive by burning property and infrastructure, impacting tourism, our local economy and negatively impacting our health from wildfire smoke.

As our communities continue to grow, as more properties are developed in the wildland urban interface, our challenges only increase. We need to become fire adapted as a community. As our forests have adapted, we must as well.

Accepting that fire is part of the landscape is the first step to becoming fire adapted, and that landscape is why many of us have chosen to call the Kenai Peninsula our home. One of the things that have become clear to me is that reducing the risk and potential impacts of wildfires can’t be solely managed by state and federal land management agencies.

Within our communities, people and property owners have a key role to play utilizing fire prevention practices, understanding personal preparedness for areawide emergencies and adopting firewise principles.

Creating defensible space around your property, reducing hazardous fuels and making your communities fire adapted or resilient to the impacts of future wildfires are things you can do. In turn, we can provide the tools, information and the most current science available.

By being a firewise community, we become more resilient to fire, a natural part of the landscape. We can also do this for our neighbors and the first responders tasked with protecting our homes in the wildland urban interface as part of all of our efforts to adapt to living with fire.

Jeff Bouschor is the Fire Management Officer at Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. To learn more about the fire history and fire ecology of the refuge visit: https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Kenai/what_we_do/science/fire_ecology.html Find more Refuge Notebook articles (1999–present) at https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Kenai/community/refuge_notebook.html

By JEFF BOUSCHOR

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge