Being a seasonal biology technician has its perks. Every summer is a new adventure full of incredible fieldwork, new friends and amazing locations. Much like caribou, I tend to migrate throughout the year from wintering in Anchorage or Fairbanks to summering all over the state, much like the life of a caribou.

Caribou migrate farther than any other known land mammal. While the caribou on the Kenai Peninsula migrate around 100 miles each year, there are herds located in northern Alaska that migrate around 800 miles traveling between their summer and winter ranges.

Why bother making such arduous journeys each year? While living in a herd provides safety in numbers, finding sufficient food to prepare the whole herd for harsh winters is no easy feat.

By migrating across large ranges, caribou ensure their food sources — lichen, willow and birch — have time to regrow.

In spring, caribou head toward areas with rich plant growth and open space to raise calves away from stalking predators. As the weather turns, herds move toward sheltered forests with lots of lichen, their primary winter food.

Caribou tend to use different parts of their ranges each year, allowing more time for plants to regrow.

Animals that migrate utilize routes called migration corridors to travel in between their seasonal ranges.

While on these migration corridors they often stop to rest and refuel at places called stopover sites during travel throughout the migration corridor. Identifying and conserving these areas is crucial for the success and health of the herd.

Within the Kenai Peninsula there are four distinct herds of caribou. These herds were established by a reintroduction event on the peninsula in the 1960s by a cooperative effort by U.S Fish and Wildlife Service and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

Herds present are the Kenai Mountain herd, Fox River herd, Killey River herd, and the Kenai Lowland herd.

The Kenai Mountain herd occupies the northeastern portion of the refuge and has herd numbers of 200 to 300 caribou.

The Fox River herd numbers around 50 to 75 caribou and occupies the area south of Tustumena Glacier in the Upper Fox River and Truli Creek drainages.

The Killey River herd is the largest herd on the refuge with around 250 to 350 caribou. It can be found around the upper Killey River and the Funny and Skilak River drainages on the refuge.

The Kenai Lowland herd winters along the Moose river and the outlet of Skilak Lake and summers in and around the Kenai River flats. The herd has around 130 to 150 caribou. This population is most susceptible to human disturbances due to its migration route passing through the communities of Sterling, Soldotna and Kenai.

The Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Chugach National Forest and Kenai National Wildlife Refuge manage these four herds collaboratively. Through the use of GPS collars and aerial surveys we are able to estimate the population and the health of the herds.

With the Kenai Lowland herd being most vulnerable to human disturbances and with the Kenai Peninsula becoming more and more populated during the summer, the question arises of how we can maintain these important migration corridors for caribou.

One way we can look at these migration corridors is by monitoring their movements. In 2006, the refuge purchased and deployed 11 global positioning satellite collars on the Kenai Lowland herd. GPS collars can be programmed to collect data at different time intervals throughout the battery’s life.

These collars were programmed to collect location data every 30 minutes every day from November to April to capture the spring migration and every two hours until they fall off in September the following year.

With this location data we can run various ecological models to see where caribou are moving and spending the majority of their time.

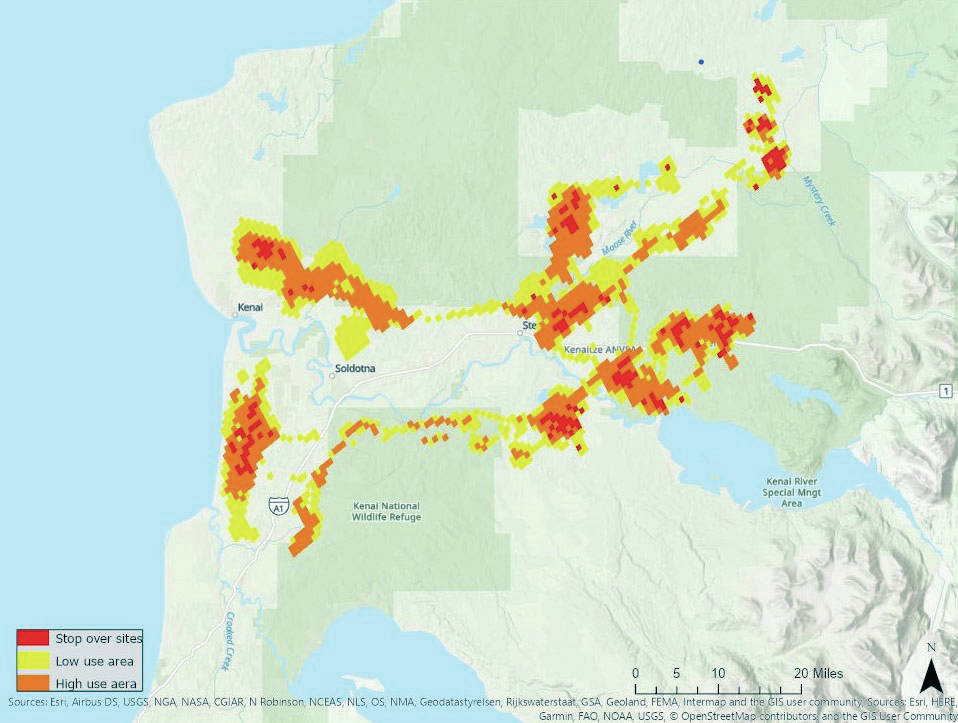

After a taxing process of organizing data from over 60,000 location points over a two-year period, we were able to obtain some preliminary results and run a Brownian Bridge Movement Model.

Although just preliminary data, this model shows an animal’s movement path and utilization distribution (where they are spending the most time) from data recorded from our GPS collars and can calculate high use areas, stopover sites and the general migration corridor.

Caribou need to be able to move freely throughout the landscape without barriers to migrate to their summer and winter grounds. Being able to make it safely to and from their summer range is particularly important as this is where the female caribou calve.

These areas are saturated with nourishing food needed for the mothers to produce nutrient-rich milk for the newly born caribou. Studies have shown that pregnant caribou are especially sensitive to human disturbances such as vehicles, roads and pets.

Human disturbances can affect regular caribou migration patterns and corridors through the development of roads and highways, increased tourist traffic, urban sprawl, and increased interactions by humans.

If humans continue to expand and develop on and within these important corridors and calving grounds this could stop caribou from using these extremely valuable areas. Expansion into corridors and calving grounds also could endanger the health of the herd by leading to a rise in young caribou mortalities, a decrease in offspring and an overall decline of health.

Displacement of caribou from their normal summer and wintering range could also lead to the congregation of caribou in less ideal areas, making it harder for them to get the nutritious food they need to stay healthy.

If development were to happen in these vital areas, the health of the herd may be in jeopardy. Protecting these areas and mitigating future development within these ranges is essential for the future of the Kenai Lowland herd.

Amanda Zuelke is Biological Technician for Kenai National Wildlife Refuge and is starting a graduate program at UAA in the fall examining the diets of brown bears across the state. Find more Refuge Notebook articles (1999–present) at https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Kenai/community/refuge_notebook.html.

By AMANDA ZUELKE

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge