When you first become interested in the world of biology, wildlife biology in particular, you never picture yourself sitting at the computer. But the reality is that even the most field-intensive projects include months of doing exactly that.

This reality is because biology, the study of living organisms, now goes hand-in-hand with the science of electronic devices. Enter what I affectionately term “computer biology,” the study of living organisms through nonliving devices.

These devices range from a laptop or remote camera trap to a program to identify individual seals by their face (like your cellphone does with you). Kenai National Wildlife Refuge’s biology team is very well acquainted with most of these products, especially the remote camera traps, otherwise known as trail cameras.

We have a well-established network of trail cameras throughout the refuge that either monitor the efficiency of animals using the wildlife crossings structures or create media content for our wonderful co-workers at the visitors center.

There are numerous benefits to using remote cameras to monitor wildlife. One of the biggest advantages is that biologists have the opportunity to observe more natural behavior of wildlife because there is reduced human presence. Additionally, unlike biologists, these cameras work around the clock, so they have a much higher likelihood of capturing images or videos of wildlife.

But with the pros always come the cons. A major downside to camera trapping is “false triggers” and “empty” images. Because most trail cameras are triggered by motion, changes in weather conditions, odd lighting and growing vegetation can all cause a “false trigger.”

One tall blade of grass blowing in the wind can end up in tens of thousands of empty images. Also, cameras in public areas usually end up with thousands of images of people, pets, vehicles and machines.

So, by the end of a field season, you may end up with over a hundred thousand photos from your cameras, but how many of those actually contain wildlife? And how much time do cameras really save when biologists must spend weeks or months painstakingly going through each individual photo to look for wildlife?

But what if you could use what I termed earlier as “computer biology” to identify and catalog these photos? Maybe even help identify individual animals? Spoiler alert, you can!

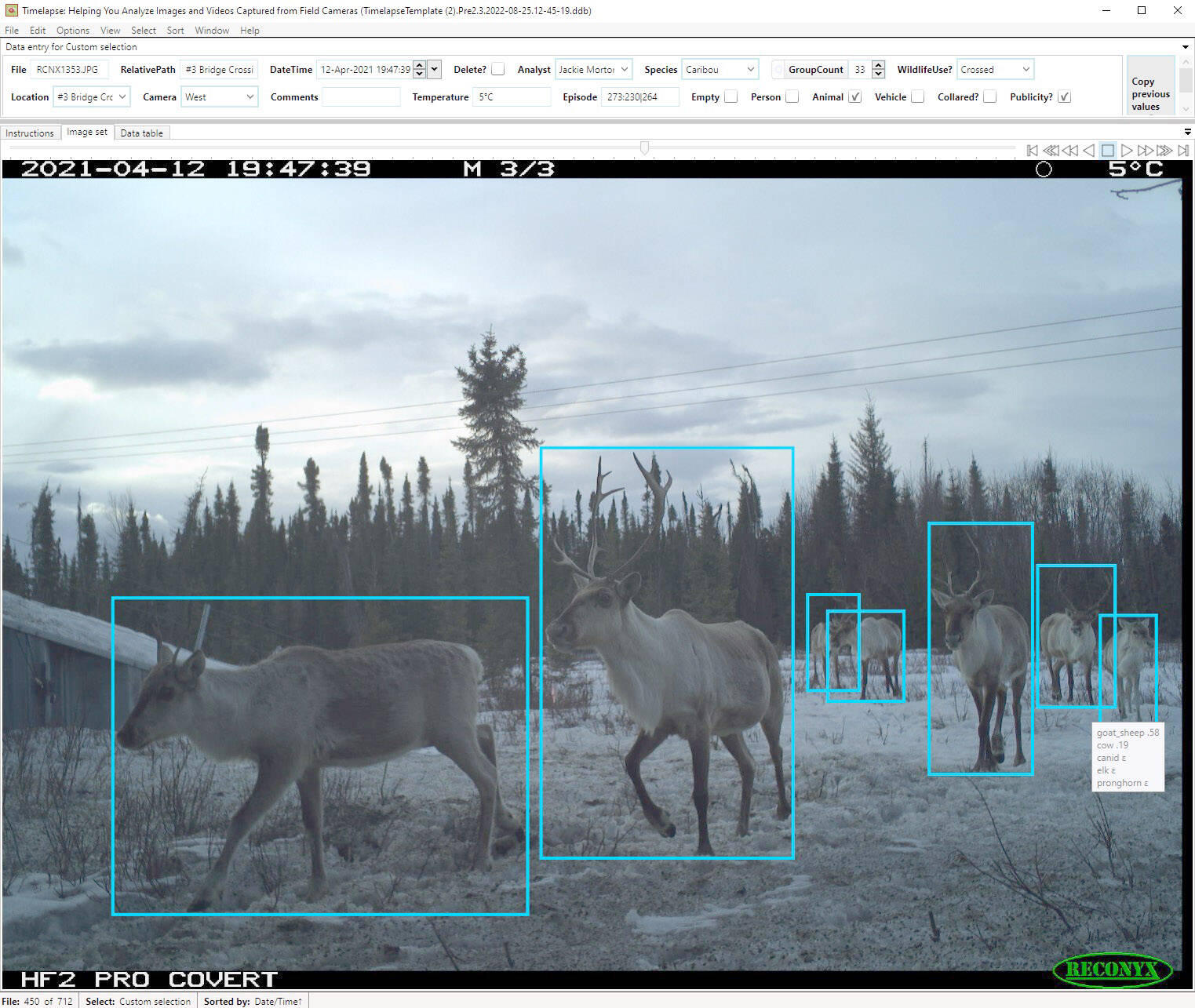

Currently, we are using innovative computer programs like Timelapse2 and MegaDetector to help us do just that. As a Seasonal Wildlife Biological Technician at the refuge, who spends a significant portion of my time working with remote cameras, I thank my lucky stars every night for this technology.

Most of the images and videos we collect are from trail cameras placed near the Sterling Highway wildlife crossing structures. In two years, nearly 280,000 images were captured from 12 remote cameras.

Timelapse2 saves us significant time processing the data from these images by automatically entering metadata taken from the image into a datasheet. Metadata includes anything from time and temperature to the light settings of each individual image.

Another added benefit is that there is no need for a separate Excel spreadsheet as the program automatically inputs the data into an integrated Excel-style spreadsheet. The program makes catching and correcting errors much easier by directly linking the image with a corresponding row in the data sheet.

We also use the Timelapse2 computer program to record and identify the type of crossing behavior (crossed, presumed crossed, approached, did not cross or unknown) to determine the efficacy of the crossings and recommend improvements. By the end of the day, Timelapse2 cuts the time I spend analyzing an image in half. With over a quarter of a million photos to process, that time adds up!

But as impressive as Timelapse2 is, you still must look through every photo individually to identify wildlife species, record the pertinent data and then fact-check the processed data. So, welcome another innovative computer program, MegaDetector, a publicly available artificial intelligence program.

With new advances in AI technology, you can code programs to detect movement and recognize species in a photo. MegaDetector is coded and trained on wildlife in the Rocky Mountains, so it comes to users already programmed to use machine learning to accurately identify moose, lynx, coyotes, bears, wolves, hares, dogs, cats and humans in images.

Empty images take up most of the time in image processing because they make up most of the photos. MegaDetector identifies not only wildlife species but also vehicles, machinery, domestic animals, people and, most importantly, these empty images.

For example, in our initial dataset of images from wildlife crossing structures, which contained 279,779 photos and videos, roughly 55% of the images and videos were empty. Only 8.7% contained wildlife, and only 5.6% of these (15,777 of the total photos) were the primary species (moose, caribou, lynx and bears) that the wildlife crossing structures were designed to provide safe crossings across the highway. Other species, like snowshoe hares, porcupines and ermine used the crossing structures as well.

Once MegaDetector was added to TimeLapse2, we no longer had to spend time identifying species and empty images. Our efforts now focused on training the AI software by introducing new species (caribou) and correcting misidentified species (elk) because the program was designed in the Rockies, not Alaska.

We had to retrain the program to the subset of wildlife on the Kenai Peninsula and then review and correct the dataset for any other mistakes. These AI errors led to quite a few laughs as the program attempted to learn that caribou were, in fact, caribou and not cars, cows, dogs or goats.

While we are taking considerable time in learning, training and correcting the AI program, the time it saves us now and will continue to save us in the future, once fully trained, is invaluable. Some studies estimate that MegaDetector (once trained) can accurately analyze photos with a similar success rate, or better, than human eyes.

One study reported that MegaDetector was 99% accurate in identifying humans in images, 82% accurate with animals and increased the efficiency of biologists by 500%! This increased efficiency means more time out in the field collecting important information!

With today’s technology already capable of so much, how do you imagine the future of wildlife biology will look? Picture this: One day, you are driving down Skilak Loop Road and think you see a lynx. You are able to capture a quick photo before it jumps back into the woods.

You upload this photo into an app on your phone, and BOOM! Not only do you get confirmation that it is indeed a lynx (and bragging rights to your friends) but maybe even insights about the life history of the lynx that you only caught a glimpse of today!

Now imagine that some of the nearly 1 million Kenai National Wildlife Refuge visitors upload data into this app. Before you know it, we have a citizen science program that contributes to science, all with the touch of a button and a little computer biology.

Thank you to Saul Greenburg’s team, the creators of Timelapse2, and Dan Morris’ team with MegaDetector for creating these great programs and being available to help resolve any issues we had!

Jackie Morton is a Seasonal Wildlife Biology Technician at the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. Find more Refuge Notebook articles (1999–present) at https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Kenai/community/refuge_notebook.html.