In 2019, I became a biology intern at the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge for the first time! Here I was met with forward-thinking and tradition-challenging scientists.

Working in the field, I identified and inventoried vegetation and forest response to fire, surveyed invasive species, and collected and processed invertebrate samples. I absolutely loved my time here. However, I was having a hard time narrowing my career interests.

The following year, I began thinking about a potential undergraduate thesis project. Because the Kenai NWR is such a unique and fascinating region, seeing rapid shifts as a result of climate change, I knew I was interested in studying these changes.

After reaching out to two of the biologists on the team, I began working remotely with some aerial imagery the refuge had collected in 2019 and taking courses at my school that would tie in closely with this kind of data.

By keeping in contact with the refuge this way, they invited me to return as a remote sensing intern for refuge ecologist Mark Laker in the summer of 2021.

Remote sensing is defined just as it sounds, remotely sensing the physical qualities of the earth from planes or satellites, which meant I would be in planes collecting and processing aerial imagery of water, land cover and wildlife. I was very new to this kind of work but ready for the challenge.

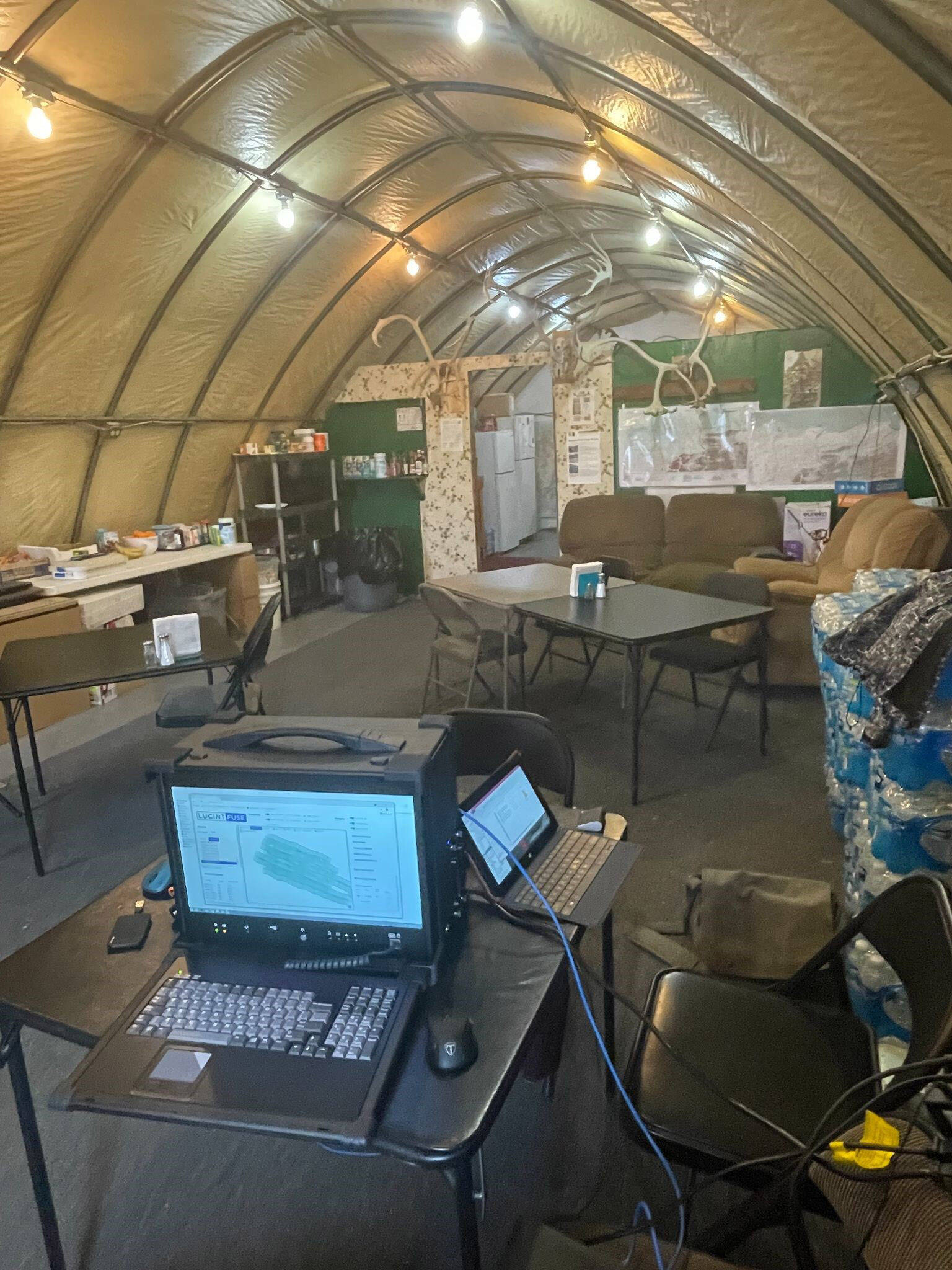

Fast forward to the end of the summer, and I find myself flying imagery above the arctic tundra by day and making excessive flight lines by night! Mark and I had made our 17-hour trip from Soldotna to Galbraith Lake, where Brett (our pilot) shuttled us and piles of cords and computers to Kavik River Camp.

This remote camp, near the Arctic Ocean and about 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle, consists of an airstrip, a few trailers, outhouses and fuel. These trailers can be rented out, which is common for those in need of accessing the nearby Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

If you are familiar with the show “Life Below Zero,” it follows the extreme lifestyle of Sue Aikens, the hardcore woman running this frigid camp year-round. When I landed, I was greeted by her toy poodle, Bob, who is not “Alaskan” enough to be featured on the show. However, he has somehow lasted 10 years without being snatched by any predators.

While we were fogged in much of our time there and even hit with some snow, we were able to fly a couple of long days, capturing thermal imagery of some major rivers running from the Brooks Range north into the Arctic Ocean.

The thermal imagery will be used to map river temperature and cool refugium, key for fisheries. These rivers are jaw-droppingly beautiful and can span miles wide, not to mention witnessing the impressive spectacle of herds of caribou grazing almost everywhere you can see and the snow geese preparing for migration along the coast.

My only complaint? There are no bathroom stops in the air. Mixed with morning coffee, things can quickly get precarious.

When we weren’t preparing for our survey, flying surveys or processing imagery, we had the opportunity to watch the local fox families run around camp, explore the surrounding tundra or play cribbage.

While this was one of the wilder places I flew this summer, I also flew imagery surveys for all kinds of projects for the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge.

On these projects, images are taken from the visible light spectrum (red, green and blue) and some from beyond the visible spectrum (near-infrared and red edge). These images are used to classify landscapes (for example, by vegetation type), identify where invasive plants reside, or build digital surface models of a given landscape’s topography.

Digital surface models are used for many things, such as delineating watersheds, creating topographic maps, determining streamflow and measuring tree height, to name a few.

Thermal imagery is used to identify the heat signatures of species like moose or caribou so that artificial intelligence programs in computers can count animal occurrence and distribution across large areas to help us understand habitat needs and trends in wildlife populations.

Thermal imagery can also be used to reveal the thermal gradients across a body of water to document changes in water temperature and understand the implications to species like salmon.

So how does this all relate to working on my thesis this fall? I plan to use RGB (color) imagery, which I validated through observations at a few on-the-ground field sites, combined with digital surface models (height) of trees to train the computer to pick out where trees versus grass lie.

I will then use software like Geographic Information Systems to describe what percentage of the landscape is grassland versus forest to help direct land stewardship and management decisions. For example, is this region experiencing late succession due to extensive disturbance, or is it indeed shifting ecosystems entirely?

Remote sensing is unique in that it can be used for a plethora of work. These projects, that I was a part of this summer, are just a small portion of how remote sensing is being used to advance conservation.

Many of these projects are developing and testing methodologies that could make a huge difference in the accessibility and efficiency of data collection. Additionally, new technology for collecting and processing aerial imagery is improving and updating every day, adding to the possibilities.

From here, there are infinite questions and answers that lie in using remote imagery within the landscape ecology field. It is this exciting career path I am taking next!

I felt lucky to contribute to such cutting-edge science and find a new and exciting direction to take in my environmental career. While I am back on the ground in Colorado, where I go to school, I’m sure I will be finding my way back to Alaska sometime soon. ‘til next time!

Frannie Nelson is a seasonal Remote Sensing Intern at the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge from Seattle, Washington. She is currently attending Colorado College and plans to graduate with a Bachelor’s of Art in Environmental Science in May 2022. Find more Refuge Notebook articles (1999–present) at https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Kenai/community/refuge_notebook.html.