On my days off I drive.

I drive to mountains and rivers and through flats — pacing the highway with wheels looking for a groove they can fall into. Sometimes I follow roads until I meet their ends.

I never have an exact destination, but I know I am searching. I didn’t know exactly for what, until recently.

Several weeks ago, to kill time on a warm Sunday evening with too much light, I drove to the end of Funny River Road — or as far as I could go before I hit an unwelcoming stretch of dirt, lined with chest-level grass.

Despite my desire to explore, and urge to see new things, I was filled with the uneasy feeling the farther I crept down the road. It was a feeling that I realized has followed me since I got here a year and a half ago: I knew I didn’t belong there.

Despite the vastness of the landscape, this place has felt cloistered and inaccessible in a strange way. And no matter where I drive, or however often, I feel a distinct sense that Alaska is trying to throw me back.

The mountains and rivers and flats are owned by bears and fish, and by those who came out and staked claims long before my arrival. Grasping for a piece of this place to settle onto, I have felt like I am in a maze with no end — or that loops back to the beginning, center unfound.

During these long summer days, the sunshine has made the pull to drive even stronger, and the sense of being unmoored even more intense.

Every place I’ve lived, I’ve eventually found a place that belonged to me. In the disorienting, mad New York landscape, where lights and people scrolled on an endless track, I found a patch of grass in Union Square. In the Pacific, my place was a corner of beach on the eastern side of the island, where the reef dropped off precipitously, and the waves crashed through underwater canyons with unseen bottoms. I could sit near rocks in the low tide, dress floating around me, listening to the waves and seeing no one else for hours. I have already written about the rickety swing under my trees in Nebraska — and there I belong too.

For last weekend’s adventure, I took advice of a Nikiski dweller, who told me to drive past the “fourth or fifth” dumpsite off the northern end of Kenai Spur, and try out Swanson Lake.

It was humid and green and as I drove north I could smell the sun-cooked cow parsnip lining the road. I stopped at the boat launch — deserted — and waited, waded, sat on the heated concrete.

A few curious people came and went, deterred by buzzing flies. I stayed long enough to get a photo of my shoes, perched at the edge of the glassy green lake, and to hear strange birds calling in the trees. I left feeling like I had yet to find a place I could grasp onto.

So I drove again, onward, to the beach at the end of the road.

The last time I had been at the beach in Nikiski there were chunks of washed-ashore sea ice as tall as me, and a cold, unwelcoming surf lapping on frozen mud. This time the sand was warm enough to shuffle my bare feet through — and the sun hot enough that I could wander without a jacket.

The far-off fires had made the mountains nearly indiscernible and the horizon more expansive. If I didn’t look too closely I could pretend there was no land at all, just water stretching toward nothing.

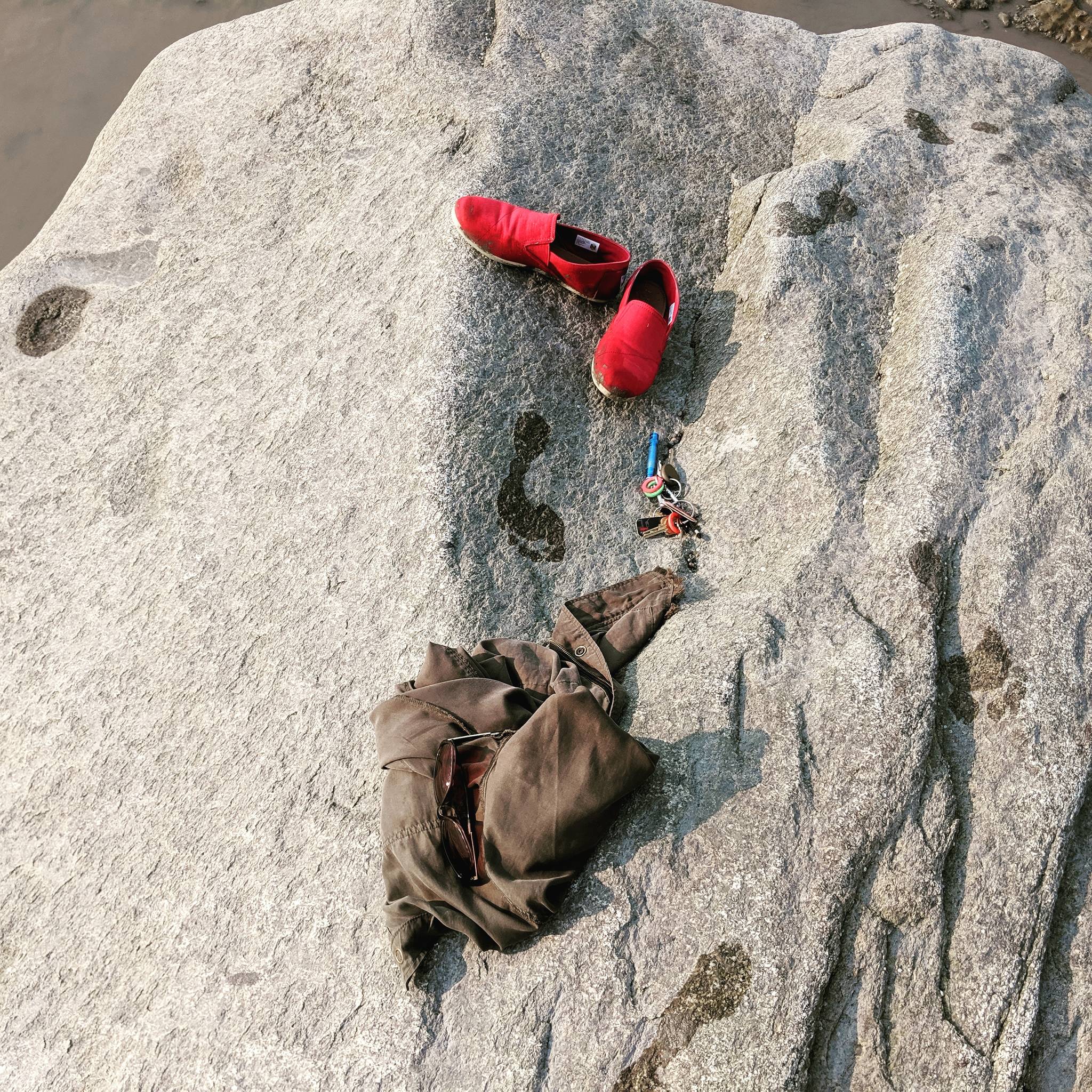

Even in what I think is peak tourist season, the beach was deserted. I trekked through the sand until I found a rock — big enough to climb and close enough to the shore that I didn’t risk falling into the mire. I fit in the hollow, lying between two warm slopes. And for an hour or so, that rock was mine.

At some point, a family with two muck-covered dogs, and several children — I think two, I was paying attention to the frolicking dogs, dashing in and out of the surf — came wandering by. The woman asked me if I had a phone. I handed it off, thinking she was going to make a phone call. Instead she stood back and took a photo of me, perched on the rock — mermaid like, except I was wearing jeans and not sporting a tail.

Maybe she was compelled to take the photo because I was taking an embarrassing number of selfies, but I’d like to think it was because I looked like I belonged on that rock — mermaid tail or no.

Eventually I jumped from my rock, and wandered into the surf. I headed as far into the waves as I could, making it nearly waist-deep before my toes sank dangerously into the sticky quicksand of the inlet’s bottom.

The inlet isn’t quite the ocean, but it’s adjacent. The waves aren’t the crystal blue of the Pacific. Silt and water churn together as the tide comes in and out, creating a muddy emulsion. As the water calms, brown ribbons separate at the top, rivulets of dust suspended in a gray soup.

But waves are still waves — and the pull of the ocean is like no other. Rivers, cold and rushing as they are, are elusive. Rivers run away from you. Lakes ask you to take steps into the unknown, and won’t reveal their secrets until you’re already head deep. They might be welcoming, or they might swallow you.

The ocean comes to you. And its ever shifting waves — crashing and overpowering — are impossible to stake a claim on. The ocean doesn’t belong to anyone. But, I’m fairly certain I belong to it.